“We happily reached Timbuktu, in a moment when the sun touched the horizon. My eyes finally saw this capital in Sudan which was the object of my deepest desires for so long. […] Recovered from my enthusiasm, I proved that the scene before my eyes did not met my expectations”.

Voyage à Tombuctú

René Caillié

René Caillié was the first western explorer who visited Timbuktu, a city forbidden to the non-Muslims, and he returned to tell his story. This city was supposed to be full of riches and fabulous treasures, since it was the place where the gold which arrived to Morocco came from, its same weight being exchanged for salt. The myth had been built up since times through the descriptions made in the 15th century by Ibn Battuta and by Leo Africanus in the 16th.

Caillié was born in November 1799 in Mauzé, in the province of Deux Sévres (France). His father, who was a baker, was convicted of burglary in 1800, and he died in the prison of Rochefort in 1808. His mother died three years after, and René was raised by an uncle. As soon as he learned how to read and write, he started an apprenticeship as shoemaker. He spent Sundays and all his days off reading anything that fell into his hands related to travels and discoveries and he dreamed of completing such adventures. It seems that his addiction began with the story of Robinson Crusoe. Africa and its vast unknown regions excited his imagination. He devoured Ali Bey’s book, the pseudonym of Domingo Badía, a Spanish military man who, commissioned by Godoy, (Spanish king Charles IV’s Primer Minister during 1792 to 1798) had travelled all around Morocco. Once Caillié completed the reading of Badia’s work, he came to his house in Paris, where the Spaniard was exiled given his condition as Frenchified. Badía welcomed him and encouraged him to accomplish his dream of visiting Timbuktu. Despite the taunts of his acquaintances, René persevered, and he left home when he was sixteen, against his uncle’s advice. In Rochefort he boarded the vessel Leire as a sailor, on 27 April 1815, towards Senegal. He landed in Saint Louis, in the east coast of this country. English people arranged several expeditions towards the interior, and they ended in failure with the deaths of their participants.

Upon receiving information of Mayor Gray’s departure to another expedition to what is currently Gambia, René walked on foot, part of the way barefoot, from Saint Louis to Dakar and to the mouth of the River Gambia (almost two hundred miles). He was not accepted there, and he then boarded towards Guadalupe Island, in the Caribbean Sea, where he worked for six months. He then read Mungo Park. He returned to Bordeaux and again to Senegal, where he arrived by the end of 1818.

He joined up, unpaid, with the Parterrieu expedition to offer aid to Mayor Gray in February 1819, where again he moved on foot and only had the right to leftovers food and water. Among the many difficulties he suffered, he nearly died due to the fevers that took him back to the coast and to France. He was able to recuperate and keep on studying and dreaming of Timbuktu. In 1824 he was back again in Senegal. He had decided that, as well as Badía did, the best way to achieve his goal was by impersonating a Muslim. This was how he invented the story of being an Egyptian from Alexandria, that Napoleon’s troops had taken him to France when he was a child, and that he longed to return home, to go back to his religion and do the pilgrimage to Mecca.

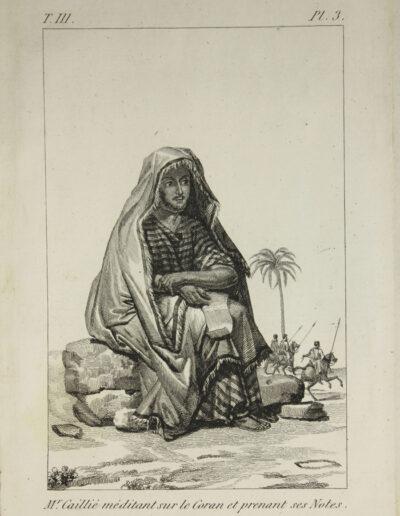

In order to learn Arabic and to get to know the Koran, he lived for four months with the Moors (Maures) from Brakna, a tribe from Mauritania, north of the Senegal River, close to Podor, where he was involved in selling trinkets that he was lent. He travelled carrying the merchandise on top of his head and barefoot. The rest travelled on horseback or on domesticated oxen. In his account, he tells the time he spent with the Maures, the different camps where he lived in, the customs, and the relationships among social and tribal groups. He wrote it all in much detail and in secret.

In May 1825 he returned to Saint Louis. He wanted to undertake the travel to Timbuktu from the north, via Walatta, but French authorities did not provide him with help. Then he was offered a job on a farm as a foreman for a pittance of six hundred francs per year. Disillusioned and disenchanted as he was, in 1826 he decided to go down to Freetown, in today’s Sierra Leona, where he worked for English people as the manager of a factory which produced indigo, used to make blue dye, where he earned three thousand francs per year. Once he had saved around two thousand, he exchanged them for fabrics, crystal beans, gold, silver, medicines, and diverse merchandises, and he moved to Uganda, to Kakondi, from where merchants departed for the interior. He got there disguised as a Maure Arab calling himself Abdallah.

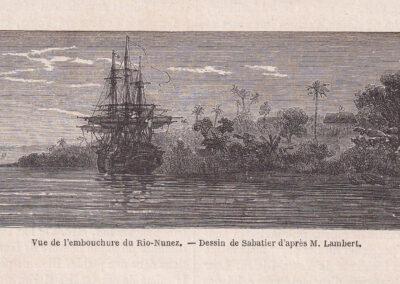

He hired some Mandinkas to accompany him in exchange for an ox, and they started the journey 19 April 1827 along the right bank of the Nunez River, close to Boke, on the border of the current Guinea-Conakry with Guinea Bissau. The first day they travelled some ten miles. The carriers bore a big staff, as high as them and, when they wanted to rest, they leaned the load, which normally had an elongated shape, on a tree branch and the staff without having to be lifted and lowered.

His nourishment consisted of boiled rice with palm oil and smashed roasted peanuts. For meals they divided the group into three parts: on the one side they were he, the guide and free Mandinkas, on the other the slave Mandinkas, and in the third one the guide’s wife, who cooked for everybody and ate alone.

After following the course of the River Nunez, they followed that of its tributary, the Naufomon. It was the rainy season, from April to September, and everything was covered with mud. They went across many hamlets and ourondes, villages inhabited by slaves, located close to the agricultural fields that were visited by the owner every now and then. Some of these hamlets were inhabited by Mandinkas and others by Fula people and Diakolés.

He wrote his notes in secrecy and mixed the manuscripts with the loose pages of the Koran pretending he was reading or writing them. People used to give him a warm welcome when he told the story of his captivity in the hands of the French and, sometimes, he got help due to his condition of being almost a compatriot of the Profet. Others begged him to intercede for them or asked to hold a place in paradise for them when he arrived at Mecca.

As they arrived at Timbo, capital city of Fouta Djallon, and after crossing the Bafing River, tributary of Senegal River, they reached the region of Kankan, where a chicken cost was the powder needed for two shots and a woman two, or three slaves. Customs duties or tolls had to be paid in every hamlet. They ended up being fed with fonio porridge, a quite tasteless cereal boiled in water to which was added a sauce made of herbs, vegetable or shea butter, although sometimes it was eaten in its own. Fevers were quite frequent, and when they suffered them, they were cured with quinine sulphate. He could not go up to through Ségou because there was a war between this city and that of Djenné, on the road to Timbuktu.

In Sambatiguila, he hired a new guide who took him to Timé, on the border of the current Ivory Coast, where it was considered that to lead a good life without having to work one needed at least twelve slaves. They teased him about his nose and his umbrella, which they loved to open and close. He was fed on yam porridge. He suffered from fever and chills. He told that he headed by copying a sura of the Koran on a tablet, washing it up and then drinking the water used. He was forced to rest due to an injury to the foot that was not healed, having to remain without walking from August to October. In November, he was afflicted with scurvy, lost his teeth, and had a cold sore on his palate that disfigured his jawbone. He was terrified at the thought that his farce would be discovered, because for Muslims, according to his own words, it was hundred times worse to impersonate a Muslim than for a Muslim to pass himself as Christian.

In January 1828, once recovered although with his face disfigured, he left for Timé, where he had arrived the 3rd of August 1827. He himself wrote that he caused great pity and disgust among the natives. In the new direction he went to, towards the northwest, the coins which were accepted were only the cowries, small sea shells. A chicken costed eighty units. They bred dogs to eat them and used rats to make sauces to serve with porridge. They believed that writing was magic, and some asked him for grigris (pieces of paper wrapped in leather bearing something written from the Koran). He was asked for many remedies, and his supply of medicines was gradually running down. Sometimes he was invited, and other times he had to pay for his meals. Salt was a luxury item, and sometimes a chicken was exchanged for the salt needed to season it.

He realised that the thatched huts were substituted with houses whose roofs were made of the same material. As they had not chimneys, and the inside smoke could only get out through the door, rooms were full of smoke, so it was necessary to sleep outside. The inhabitants of the area were mainly the Bambara people −Animists− although there were still some Mandinka −Muslims− hamlets of some of them inhabited by people of both ethnicities. Bambaras had the custom of hanging up the heads of the animals they had eaten on the walls so as to boast within the community. He learned that “soon” meant fifteen or twenty days. In the village of Tengréla, in what is now Mali, Bambaras and Mandinkas lived together; the first ones, non-Muslims, brewed and drank beer. The husband’s houses were made of mud; theirs wife’s ones in thatch.

He arrived at Djenné on 11 March 1828. He was acquainted with the death of a Christian in Timbuktu, and he assumed that it was Laing. At that time, Djenné had ten thousand inhabitants, and one could find in the market European goods, which came through Timbuktu.

He made a deal and exchanged his umbrella for a place in a canoe for Timbuktu. On the road, Tuaregs made them pay for the right to cross the river. After a difficult journey lasting more than a month, they reached the current city of Kabara, the port of Timbuktu, some eleven miles away. The Tuaregs charged him again for disembarking. He was welcomed by the slaves belonging to Sidi Abdallahi, a Maure merchant from Morocco to whom Sidi-Mbark (the man Caillié had exchanged his umbrella) requested to host him. There they loaded onto donkeys and camels the merchandise to take it to Timbuktu. They had an armed security escort so as to be protected from bandits.

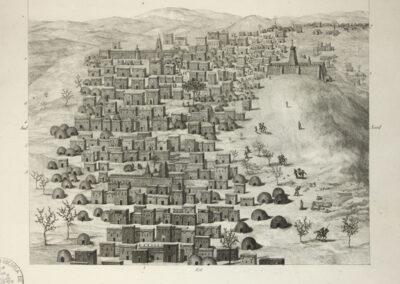

On 20 April 1828 he entered Timbuktu and was received by Sidi Abdallahi. He then discovered the false myth of wealth of the city, and that its splendours had vanished. The only thing he saw were adobe houses poorly built. After overcoming the first strong disappointment, he confessed:

“However, there is something majestic in the view of an entire city built in the middle of the sand, and one must admire the effort that their founders had to make”.

On 22 April he was informed of the departure of a caravan to Tafilet (Morocco). Being as he was very tired and sick after the punishing trek he had to make, he argued he would wait for the next one. Sidi Abdallahi invited him to stay as much as he wanted. He tells that despite the significant economic influence that the Maures had, the King of Timbuktu was black [sic]. But was Caillié named King was actually Osman, an Arma pasha of Timbuktu. He was the one hundred sixty-seventh pasha who ruled the region, the so-called Arma state, since Yuder, under the leadership of the Spanish Moriscos and mercenaries, conquered the region in 1591. René described him as a dark-skinned man, hooked nose and thin lips, which shows the broad ethnic mix of Spanish and the native population. He added that he dressed in a particular way, similar to the Maures.

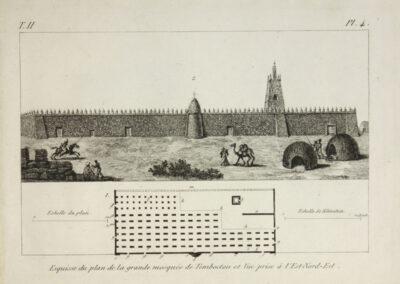

Image of the Great Mosque of Timbuktu northwest exposure and its ground floor plan.

© CC BY-NC-SA. Biblioteca / Archivo. CSIC

He tells: “Many Moors have established in this city and are engaged in trade; I compare them to the Europeans who travel to the colonies with a hope to striking it rich. These Moors then return to their countries to lead a quiet life there. They had a lot of influence on the indigenous population; however, the king or governor is a black man.

This prince is named Osman; he is highly regarded by his subjects, and his costumes are simple; nothing distinguished him from others; his clothing is similar to that of Moroccan Moors; there is no more luxury either in his residence than in that of other traders.”

Caillié explains the trade among Morocco, the Mediterranean (Tripoli, Tunis and Algiers) and Timbuktu, the departing point of merchandise, particularly salt, from where they were distributed along the Sub-Saharan Africa. He describes the city in much detail, with a population of approximately twelve thousand, of a triangular shape and three miles of perimeter, the houses, streets and the seven mosques. He highlighted that of Djinguereber in the southwest; Sankore in the northeast and Sidi Yahia, in downtown, mapping them accurately although not mentioning their names. He used to spend much time on top of the minaret of the Djingereber mosque, pretending he was praying, but using that time to write without being nor disturbed nor noticed. As a proof he had been there, was the detailed interior ornamentation he meticulously drew, which otherwise would have been impossible to do. He points out that the western part of the mosque is very old and it is better built than the rest. Caillié did not know that that part was built in the 14th century by the Granadan architect Isak al-Sahili.

He tells how they depended on the Tuaregs’ attacks, to whom they allowed to do so, and paid them a tribute so as to prevent their attacks on their own caravans. On the contrary, the Peuls, who live in certain areas of the region, were not subjected to the nomads of the desert because they did not have the wealth they lusted after. The region is so barren that even the forage for the animals, the bourgou, had to be transported from the inner Niger delta, the grass growing after the flooding of the river. They also bring the expensive firewood from the riverbank, which the poor replaced with dried camel dung.

On 5 October 1828, the Société de Géographie in París and palaeontologist Georges Cuvier awarded him with ten thousand francs. Later, he was awarded the Légion d’Honneur (Legion of Honour) and a lifelong pension. In 1880 the Journal d’un voyage à Tembouctou et Jenné was published. He was reproached by having devoted to the city of Timbuktu only one chapter out of the twenty-seven that made up the work. The number of pages accounts for twenty-eight out of the seven hundred eighteen covered in the current edition. In his favour, it is necessary to say that his trip was as interesting as his stay in Timbuktu, as well as the impossibility of extending it. His account is filled with numerous and detailed descriptions of everything he saw, local agriculture, soils, the plants he saw, with their corresponding Latin names, the tribes and the different social groups and their customs.

He repeatedly denounced the situation suffered by slaves and women. Despite his detailed and accurate descriptions, he felt a certain inferiority complex due to his self-taught background, which he feared might be incomplete. His account in the first five chapters deals with his stay in Africa and his participation in the English expeditions. In the sixth he starts the account about his travel to Timbuktu. The journey took seventeen months to cover some three thousand miles. Almost all the distance was covered on foot everybody travelled and with poor nutrition. He was underestimated. Many “parlor-explorers”, so smug about themselves, could not admit that a “nobody” could have achieved by his own means what many had tried. He was neither a coloniser nor a soldier; he was neither supported or sponsored by any public or private institution. It was an entirely personal adventure. He achieved his goal with his own savings as a worker, a true example of tenacity and perseverance.

In 1836 he longed for a return to Africa, but his ill health prevented him to do so and he died by mid-May 1838, aged 38, married and father of four sons, in Saint Symphorien du Bois, where he was the mayor.

Others came after him: Heinrich Barth, in 1854, impersonating a Turk; Oscar Lenz and Cristóbal Benítez in 1880, also disguised as Arabs, following almost the same itinerary, but in the opposite direction. They all agreed with Caillié’s accounts.

In 1893 the city was conquered by the French with an army comprised of Senegalese. The myth had fallen, but the allure, for whoever wants to feel it, endures.