Between the Alhambra and Timbuktu.

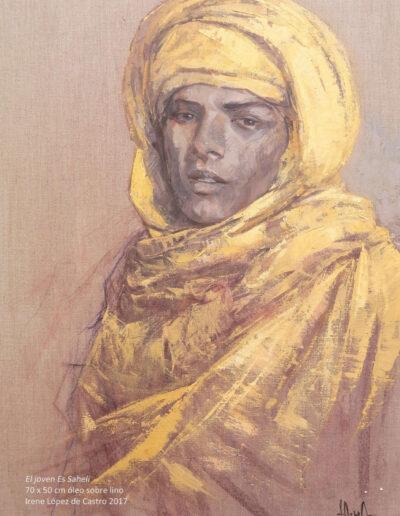

Abu Ishaq al-Sahili, Desert Architect and Bridge Between Civilizations

By Youenn Rault

Cultural Manager. Maison de France, Granada.

Though rarely mentioned in schoolbooks or lists of great architects, al-Sahili’s life and work deserve a prominent place in our collective memoryTo know his story is to understand once again that beyond geographic or cultural boundaries, there exist deep connections that have woven—for centuries—a Mediterranean of exchanges, dialogue, and shared creation. Al-Sahili reminds us that culture has no sole owner or fixed homeland: it is, by nature, universal, and its richness flourishes precisely at the crossroads—where deserts meet gardens, and mud cities echo the elegance of marble palaces.

[i] Tuwayjin in Arabic means “little cauldron”.

Granada: Cradle of Letters and Exile of Genius

Born in Guadix and raised in a prosperous family of merchants and scribes, al Sahili excelled early in the arts of rhetoric and Islamic jurisprudence. He likely received a rigorous education in the madrasas of Granada, mastering grammar, logic, Malikite law, poetry, and Qur’anic commentary. In the Nasrid court, he was celebrated as an exceptional rajub adib—a man of letters—compared by some to the legendary al-Mutanabbi.

The eminent chronicler Ibn al-Khatib, secretary and vizier to Sultans Yusuf I and Muhammad V, described him as “a unique thread in the fabric of letters,” unmatched in both prose and verse. His refined, emotional style made him one of the most admired voices of his time, capable of weaving classical Arabic forms with the subtle tone of looming exile.

However, his intellectual ascent coincided with a period of courtly intrigues and political tension. Sometime after 1321, he left Granada and embarked on the Hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca, traveling through Egypt, Syria, and Iraq. According to Ibn al-Khatib, this departure may not have been entirely voluntary, a possibly exile as a result of envy or political rivalry. From Marrakesh, he wrote a heartfelt farewell letter to his compatriots, invoking Granada as the “land of generosity.”

A Holy encounter in Mecca: Poetry and Gold in the Sands

During the Hajj of 1324, in the sacred streets of Mecca, the Granadan poet met one of the most enigmatic figures of the 14th century: Musa I, better known as Mansa Musa, emperor of the vast Mali Empire. This legendary monarch —famed for his caravan laden with gold, slaves, scholars, and camels— was not only fulfilling a religious obligation but also showcasing the grandeur of his empire to the wider Islamic world.

His passage through Cairo caused such a stir that Mamluk chroniclers noted the economic disruption resulting from his largesse. But beyond gold, Musa was seeking something more enduring: spiritual recognition, technical knowledge, and cultural prestige.

Upon hearing al-Sahili’s poetry, Musa was captivated. The Andalusi’s erudition, mastery of language, and narrative artistry moved him deeply, and he invited al-Sahili to return with him to West AfricaWhat followed was not merely a migration, but a migration of knowledge—a poetic, architectural, and political transfusion. Al-Sahili accepted, bringing with him the intellectual legacy of al-Andalus.

Timbuktu: The brown sister of the Alhambra

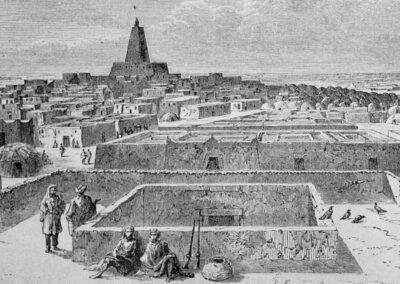

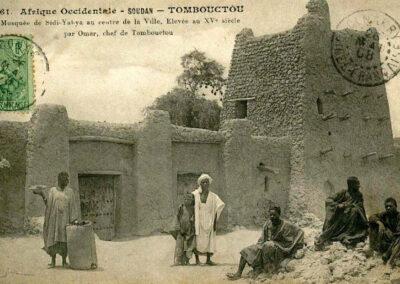

In Timbuktu, then a growing center of trade and scholarship, al-Sahili transitioned from letters to architecture —or rather, to mud. Though not an architect in the modern technical sense, his literary training, aesthetic sensibility, and familiarity with Andalusi architectural forms made him an innovator in earth and timber.

He built for Mansa Musa a square-plan audience hall, a throne room which, according to Ibn al-Khatib, resembled the palace halls of the AlhambraThis detail, barely preserved in the sources, offers a glimpse of an “African sister” to the Alhambra in the heart of the Sahel. Thus, in Timbuktu, a Hispano-Arabic architectural language bloomed—adapting to adobe, palm wood, the Niger River winds, and the red sands.

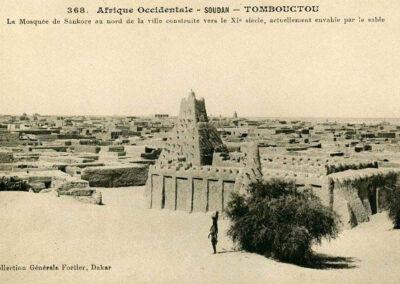

Al-Sahili’s most enduring work was the Djingereber Mosque, completed in 1327, which became the spiritual core of the University of Sankoré. Its lines reflect the Western Islamic architecture: semicircular arches, austere symmetry, majestic proportions. Although the Sudanese style preexisted, al-Sahili’s hand incorporated a new technical and symbolic language adapted to Sahelian environment. He introduced the use of baked bricks, wooden beams as seismic stabilizers, and a spatial conception that harmonized the functional with the ceremonial.

His influence, though not institutionalized, shaped the architectural idioms of later West African builders.

Sahelian monumental design after al-Sahili cannot be fully understood without his imprint.

An Exile Echoed in Verse

Al-Sahili’s relocation was not purely however. Ibn al-Khatib notes he was magrubban or ma‘badan—“banished or expatriated”—barred from returning to Granada.

From Marrakesh, he penned a letter filled with longing: Granada, the “land of generosity,” remained etched in his memory, where wise men and virtues throve. “Everything in Granada awakens my nostalgia,” he wrote. His letter, composed “in the language of longing,” offers a deeply human testimony to the emotional rupture of diaspora—even when it is cloaked in glory.

His pen evokes the pain of separation through imagery of lost gardens, silenced fountains, and friends whose voices he no longer hears. Nostalgia, for him, was not a fleeting sentiment, but a poetic force that permeated his life and subsequent work.

The Invisible legacy: culture, exile, and memory

Al-Sahili died in 1346, having attained prestige, wealth, and descendants —some of whom settled in Walata, in present-day Mauritania. Ibn Battuta, visiting Timbuktu in 1353, mentioned meeting one of his descendants. Ibn Khaldun also credited him with the construction of the mosque in Gao, noting its originality and the use of fired bricks.

But beyond buildings, his greatest legacy was being a symbol of intellectual mobility. Like the caravans that crossed the Sahara with manuscripts and salt, al-Sahili carried ideas, verses, and techniques that united two worlds. He was an emissary of cultivated al-Andalus who found in West Africa a new homeland and a renewed voice.

Today, as the Alhambra’s walls continue whispering Qur’anic verses and Djinguereber endures the sands of time, the bridge al-Sahili built between Granada and Timbuktu still stands —made of words, earth, and memory. To remember him is not merely an act of historical justice; it is an invitation to read history as a living fabric of mutual influence, where even a banished poet can raise symbolic empires.

By Youenn Rault

Cultural Manager.

Maison de France, Granada.

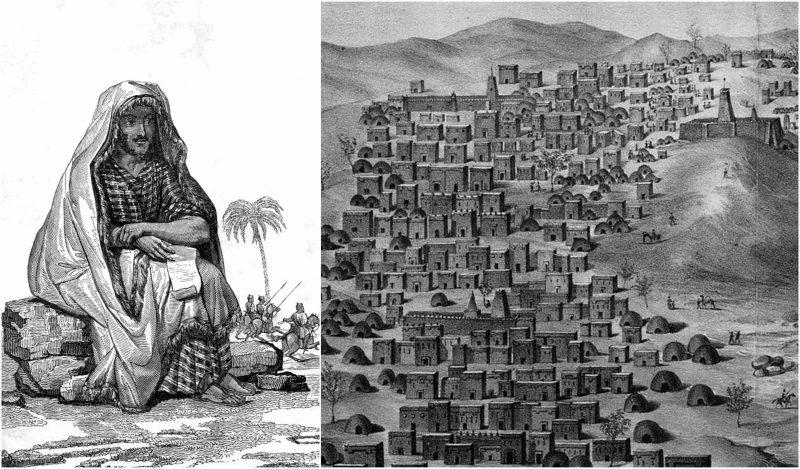

Post card of Timbuktu from 1905-1906, with Sankore mosque of in the foreground, published by Edmond Fortier.

René Caillié, the first European who survived Timbuktu to tell his story.

The mysterious and unknown city was famous due to the many descriptions of it that circulated in the Middle Ages penned by illustrious authors like Ibn Battuta or Leo the African. So much so, that the geographic societies offered large rewards to those who had managed to escape the city and bringing in an accurate description of it. René Caillié succeeded, he returned to France and was received with honours. He was awarded the price of the Geographic Society, worth 10.000 gold francs.

- Ibn al-Jatib, Lisān al-Dīn. Al-Iḥāṭa fī akhbār Ġarnāṭa. Edición moderna revisada.

- Hunwick, John. Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire. Brill, 2003.

- Ibn Battuta. Riḥla. Ed. Defrémery y Sanguinetti.

- Ibn Jaldūn. Kitāb al-‘Ibar.

- Niane, Djibril Tamsir. Historia general de África. Volumen IV . UNESCO, 1984.

- Levitzion, Nehemia. Ancient Ghana and Mali. Methuen, 1973.

- UNESCO. Tombuctú, Patrimonio de la Humanidad, 1988.

- Levtzion, Nehemia & Hopkins, John F.P. Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West African History. Cambridge, 1981.