The african deed of Judar Pasha

There are some discoveries we search for and others that are found by chance, such as mine with Judar Pasha, a conqueror of a standing equal to Cortés and Pizarro and of a similar era, although inconsequential given his position in the dark side of that Spain which hid his deed, known and silenced by Phillip II.

.

In the ruins of Sijilmasa, in the southern Atlas Mountains range, I met a professor from the University of Fez who talked to me about a Spanish man who had crossed the Sahara in 1591, with four thousand Andalusians, mostly from the Kingdom of Granada. He defeated an army twenty times superior and conquered the empire of Sudan. At first I thought that the story was not real, but I researched it at the School of Arab Studies in Granada and the name of Judar Pasha existed, although only in passing references: Julio Caro Baroja in Los Moriscos; an article by García Gómez in the Revista de Occidente entitled “Españoles en Sudán”; another essay by Costa Morata in the magazine History, in 1977, as well as one by Professor Iniesta in Historia 16, in 1981 I tried again at the University of Pennsylvania, and texts began to pile up in the computer. There were documents from English spies who told Queen Elizabeth about huge fortunes that came to Marrakesh on behalf of Judar and, urging her to side with al-Mansur, as this monarch was one of the richest kings on earth.

Finally, I found the text in Arabic quoted by all of them, the Tarikh al-Sudan, a Sudanese chronicle by es-Saidi, a wise jurisconsult from Timbuktu “born on 28 March 1596, five years after the arrival of our conquerors.” It tells the story of the empire Songhai and stressed the special relevance of a person named Judar “native of Cuevas del Almanzora, of small stature and blue eyes.” He highlights judar’s intelligence and strong leadership, as well as the goodness and success he benefited from all sorts of tasks he undertook. I also found important French papers, by Houdas and Slane, as well as the Tarikh el-Fetch, written by Mama Kati, who compiles data and notes left by his father. The most important study is, without doubt, the one by Henri de Castries, Hesperis, 1923, entitled “Conquête du Soudan par al-Mansur”, another by Delafosse, which corrects the itinerary Castries marked out, and another by La Chapelle, who retraced again the route of Judar through the Sahara.

I also unexpectedly found the account of one Spanish Anonymous; perhaps written by a monk, a Jesuit, or an ambassador of Phillipe II, telling the story of the Sahara crossing, since the departure from Marrakech in twenty magnificent pages. However, it leaves many gaps about Judar’s childhood in Cuevas and his youth in Marrakech. The account of this Spanish Anonymous is included in the Book of the Jesuits, which archbishop from Seville Rodrigo de Castro ordered to be compiled in 1595, just over six years after the conquest and published by Jiménez de la Espada in 1877. Later, I found a wonderful text written by Ortega y Gasset entitled “Frobenius’ ideas” published in El Sol in 1924, where Ortega recounts the vicissitudes on the conquest.

Timbuktu

It ends with the following paragraph: “Located where the Sahara ends and Sudan starts, on the Niger Delta, is the sacred city of Timbuktu, where up to 1900 no more than three or four European have entered. Those were the times when it was a huge city and because of this everybody quarrelled time after time, the desert people and the kings of the tropics. Well then, for the past four centuries our relatives have lived there. By the end of the 16th century, a Moroccan sultan pretended what seemed impossible: taking Timbuktu from the Touareg people. To that end, he hired a great number of Spaniards with firearms, the first ones that had appeared in this deep African spot. Spanish soldiers won the greatest battle that our people have ever won beyond the Strait, and after victory, they settled in Timbuktu; they took women from the country and created lineages that still persist. Proud of their Hispanic origin, they kept a sophisticated aristocratic discipline, and their families still represent the noble essence of the country.”

We hardly know anything about the Hispanic origin of Judar or Jawdar, Jaudar or Xaudar, as he is indistinctly named in the Spanish Anonymous.

View sta de Gao, territorio del imperio sonhai, situado a orillas del río Niger, al noreste de Mali.

We know step by step about his deeds through the Sahara and the conquest of the Songhai empire of the Askia (king) Isak II from Gao since he left Marrakech with his army and returned to the city to help al-Mansur when his empire was disputed among his three sons. We know he was a native of Cuevas del Almanzora, in the province of Almería. In the baptismal certificate of 1562, likely the year of his birth, there are the names of two boys, one of them, Diego Cervantes, with a clear Morisco lineage.

The name Judar, which means “small and strong” in Arabic, might have been the nickname bestowed on him by his own troops. One can imagine him as a small child; he could have been captured by one of the many Turkish razzias along the Almanzora River, and that he had entered into the service of the caliph of Marrakech, becoming “a eunuch, an elche (Morisco) and a renegade”, the tragic fate of all the kids who entered into his service. He might have also arrived after his expulsion from Spain. Dominguez Ortiz and Charles Lea state that between five hundred thousand and one million people were forced out, and they were no doubt in search of a homeland like the one they had left in Spain, a new Andalusia. The only certainty is that we hardly know about his Marrakech years, excepting that he became caïd (governor) of the city, as he was fully trusted by al-Mansur.

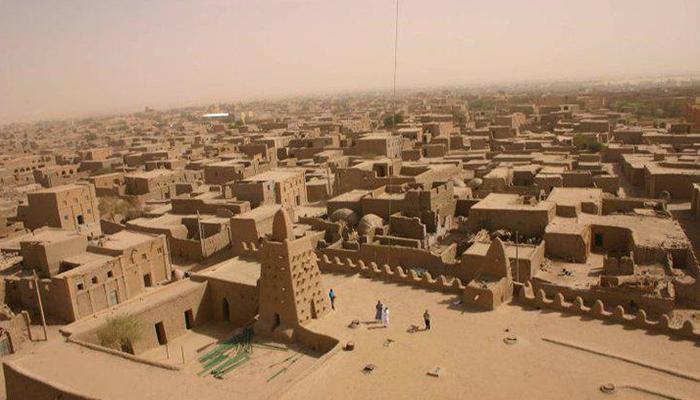

Imagen antigua de la plaza de Jemáa el-Fná de Marraquech, con el alminar de la mezquita Kutubiya al fondo, en una fotografía de principios del siglo XX.

Remains of the temple of Amum, west of Jebel Barkal, in modern day Sudan.

The three empires involved in this trade were Ghana, Mali and the Songhai empire. In the 8th and 9th centuries, Ghana was connected to the caliphate of Cordoba, giving the Umayyads complete control of their gold which he coined in dinars. This trade circuit was taken by the Almoravids and the marabutin (or maravedíes, the old Spanish coin) were minted in Valencia, a situation that the Almohades maintained until 1212, the year of the fall after the battle of Navas de Tolosa. In the 16th century, the empire of Mali was at its peak, while the mines in Hungary, Bohemia and Transylvania suffered a significant reduction. In the 14th and 15th centuries, the only larger gold deposits, seemingly inexhaustible, were those of Bilad al-Sudan. Mansa Musa, by moving the Malinke capital to Timbuktu, started the creation of its myth of this city. The main commercial cities though which gold passed were Kumbi, Salé, Oualata, Ouadam and Chinguetti, although the richest ones were Timbuktu, Djenne and Gao, which we could call the gold triangle.

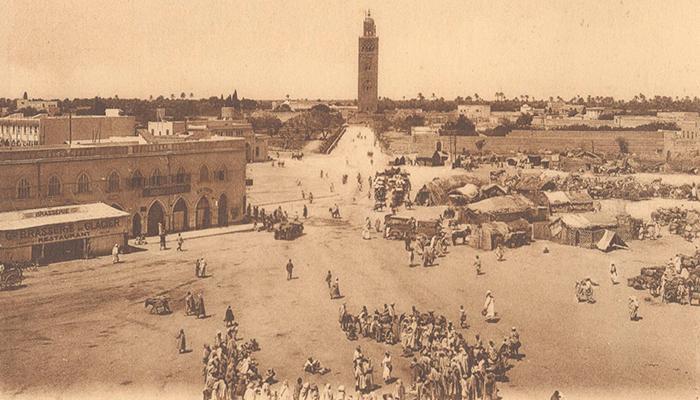

Fragmento del mapa del mallorquín Abraham Cresques, del siglo XIV, conocido como el Atlas Catalán, donde se representa la figura del rey Mansa Musa mostrando una pepita de oro de grandes dimensiones.

Jewish communities were the ones in charge of controlling gold among the cities of Sijilmasa and Tlemcen, thanks to which Majorca could elaborate maps as detailed as the Abraham Cresques of 1375, where Mansa Musa appears holding in his hand a huge gold nugget. The architect from Granada al-Sahili, the same who built the great mosque of Djinguereber in Timbuktu, also built three palaces for Musa to store the gold, which are lost today. The key episode in the life of this monarch was his trip to Mecca in 1314 carrying more than three tons of gold, the price of which plunged in the European markets. Ultimately, the gold of the black people became one of the key elements of the European economy, and the final results were but the attempts from one and all to break the Sahara’s barrier to take hold of these deposits.

With gold and the alliance with Elizabeth I of England, al-Mansur dreamed of sharing the Spanish empire with her. What al-Mansur did not consider was that the rich deposits of gold were not in Timbuktu anymore, but in the Fouta Djallon, where River Niger springs along the border with Senegal. From here it was taken in powder to Djenne, Timbuktu and Gao, from where the large caravans towards Morocco, Tunisia, and Egypt and departed.

Ríver Níger

Judar fought with them in Tondibo, and thanks to the cannons and the arquebuses the battle went shortly after in his favour. From there he departed to plunder Gao, as he had promised his men, but he later prevented it, as he did in Timbuktu, where he ended up locating its capital given the unhealthy climate of Gao, where he lost four thousand men in a few weeks. The Spanish Anonymous tells that Gao was a dead town without defences, for the greater part of its dwellers had fled. The king owned some thirty river barges on the opposite shore, and the three hundred ones that traders, fishers and the islands’ rice growers in the fleet had been either stormed or sunk due to the overload of gold they carried, and their sailors became prey to the many crocodiles there. They saw only old people, poor women, and children with spindly legs, who were the ones who came out to welcome them together with the mayor, Khatib Mahmoud Darami, an old man with a wrinkled face, who was also the preacher of the famous mosque of the Tomb of the Askia, surrounded by a crowd seeking clemency, and Judar ordered that they should not be harmed. Once they were in Gao, Judar’s people started to get sick, and many died, which led his captains to panic, becoming so frightened that he had to leave toward Timbuktu with his people.

Nor did Judar consent to take Timbuktu. The dignitaries came out to lend obeisance to them. Everyone excepting the Great Cadi, Abu Hatch Omar. Judar was not indignant about that, but his exquisite political instinct prevented him from expressing his anger. He entered the city heading his troops, choosing Sarakaima as his headquarters; then he went to see the Qadi and kissed his head and feet, with the friendliness of a subject who keeps the norms of what is written before him. His objectives were clear.

Judar had already considered the idea of creating a new Andalusia for the large diaspora of the Moriscos; that is why the country was not devastated upon the caliph’s orders, and he entered into negotiations with the Askia. Al-Mansur got very angry, and Judar was summarily dismissed.

El robo de la famosa biblioteca, compuesta por cerca de cien mil manuscritos, y su traslado a Marraquech es uno de los episodios más rocambolescos de esta historia.

These were bad times for Judar. His substitute, Mahmoud Ibn Zergun, was covetous and expeditious. He plundered Timbuktu, reduced the Niger Delta to a bloodbath, stole its famous library, sent hundreds of slaves to Marrakech among them in handcuffs the wise man Ahmed Baba, and finished his life in the Dogon country. Zergun was not a very sagacious man; the large gold caravans stopped going to Timbuktu and the city was dying like a terminally ill patient.

The theft of the famous library, composed of around a hundred thousand manuscripts and its relocation to Marrakesh would delight Hollywood. Mahmoud Ibn Zergun sent it to Marraquech in a caravan, as a gift to the caliph, who was in Fez at that moment. In order to avoid the pirates of Salé, they sent it to Tangier by sea, and almost upon arriving there a Spanish fleet appeared before them. It was commanded by Don Álvaro de Luna, who would take it and relocate it in the Escorial, where today it compounds the Arab collection of its library. Once Mahmoud Ibn Zergun disappeared, four more pashas followed, and all of them died mysteriously: Mansur Abd-er-Rahman died from very fast fevers in Karakara; Abu-Ikhtyar also died in a mysterious manner; Mohammed Taba was abandoned by his men during siesta time; and Mustafa al-Torki was poisoned, or maybe strangled, between Kabara and Timbuktu, according to al-Saidi, who adds that the reasons were the disagreement with Judar on account of the command of troops. They all were buried with honours in the mosque Sidi Yahya, and nobody doubted whatsoever that Judar was behind all these deaths, and that he definitively remained in command of the troops.

According to all accounts, it is clear that he was an extraordinary man, very concerned and human, with “spear-iron” coloured eyes, pampered by the court, but with his own ideas and a strong will to achieve his objectives with the least bloodshed possible. He did not want to cause havoc in the country as the caliph had commanded; he just wanted to rule it, and he immediately started to reorganize the colony, opening wells and channels. On 24 July 1598, al-Mansur fell ill, and he commanded Judar to return to be in charge of his army to pacify his three sons. Judar delayed the answer until being convinced by his generals that he should go back. The colony needed settlers and soldiers, and they could not live with their backs to Morocco. In The secret relations of Morocco, it is told the victorious entry of Judar into Marrakech, with all streets decorated with weavings and carpets. Judar would rule the destiny of Morocco from 1599 until 1606. He handed to al-Mansur his two eldest sons handcuffed, and advised him to kill them, but the caliph refused. The second one, Abu-Fares, was appointed caliph, and due to his negligence, he lost his army in el-Sus.

Mezquita de Yinbereber en Tombuctú.

The Arma first operated like any army, with a right wing (the aluchi or foreigners), a left wing (the Moriscos from Granada) and a support corps consisting of tribal militia. According to some accounts, in 1670 a religious leader from el-Sus, named Ali Ibn Haida, took refuge in Sudan, under the protection of the bambara king Biton-Kutubali, who had just taken Timbuktu. He received two beautiful Andalusian captives as a gift, and through this, the Arma occupied again the top military and political posts in the kingdom. From 1700 on, the main conflicts the Arma had were with the Touaregs from the east, known as aul-limiden, who pillaged Timbuktu repeatedly. Even worse was the invasion in 1833 by the fanatical Shaitu Ahmadu, who destroyed the pasha’s kasbah, in the lot where today is the townhall.

On 16 November 1893, the French invaded Timbuktu and an Arma delegation travelled to Morocco looking for help to get rid of the invader. When they came back, one of them, the wise man Mohammed Ibn Essoyuti, convinced them to lay down their arms and accept God’s will, as the country was at peace.

Mapa del recorrido del río Níger, a su paso por Mali.

When Zidan caught him and condemned him to death, Judar told one of his servants: “when you are back in Timbuktu give my regards to my friends, then take a walk by the Niger whispering my name and give them my greetings. Tell them that I die yearning for the land where they live and that they are my family, perhaps in this way they will never forget the dream of victory.”