Ali Bey, or Domingo Badía, a spanish traveller of the enlightenment around the Arab world

In the early 19th century, after the scientific expedition to Egypt organized by Napoleon to document the encyclopaedic work Description de l’Egypte, a Spaniard named Domingo Badía was also delving into those lands, although not with the purpose of study. He was a spy sent by Manuel Godoy, Prime Minister of king Charles IV, and Badía became known to history simply as Ali Bey, The traveller. Yet, our character Ali Bey lives on in documentary memory as Godoy’s spy who entered Mecca disguised as an Abbasid prince.

Born in in Barcelona in 1767, Domingo Badía Leblich grew up in Andalusia, and years later he settled at the court in Madrid.

Domingo Badía was one of the first luminaries of the Century of Enlightenment, a curious man who wanted to live the reality of all the Moorish stories, as an early Romantic in search of one thousand and one tales. Badía Leblich was a self-taught dreamer with an inquiring mind. His travels are as accurate as those of a skilled geographer and their story is legendary.

Ali Bey’s character surpasses fiction, for his story was written only at a time when that adventure could only be realistic ̶ that of a man who got deep into Morocco, Egypt, Tripoli, Cyprus, Arabia, Turkey and Palestine ̶, at a time when those names were just found in the oriental imagination of the Europeans.

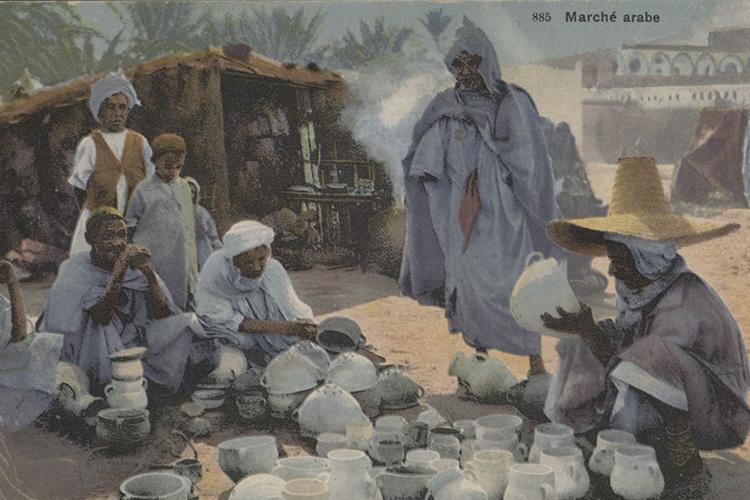

After his early childhood, his family moved to the city of Vera (Almería) where he knew many Arab legends. There, he established contact with the Islamic world through the Berber traders and the Spanish renegades who had set themselves along the North African coasts. One can imagine Badía listening by the shores of Almería to the stories about the Court of the sultan or the black stone in Mecca. Those stories awoke in Domingo Badía the interest in those imagined worlds; he was devoted to reading geography and mathematics books, to delineation and drawing, to the study of astronomy, physics, and music, as well as to the learning of Oriental languages, even though current researchers still doubt how would he have learnt Arabic. What is certain is that we are facing a Domingo Badía who was born in Barcelona, although his education and the genesis of his subsequent adventures had an Andalusian origin.

After marrying Luisa Berruezo in Vera in 1792, he decided to settle in Madrid ̶ after failing in an endeavour consisting in the promotion of aerostatic balloons ̶ to solve his economic hardship first, and then to find a better scientific forum, since there they were the academies and the possible financial ways to sponsor his major project: travelling inside the African continent.

In Madrid he frequented scientific circles and gatherings where he maintained an aristocratic air despite his stifling economic situation. He saw only one way out, as much to accomplish his dreams and concerns as, to fill his empty pockets, his African plan. That journey might provide him with renown and the money he needed, and hence his effort would be rewarded as well as his task as a researcher. He studied the trips made into Africa by the sharif Hadfee Abdallah and other Muslim scholars, and he found that no hostility amongst those faraway lands was reported in those accounts, nor in those called Berbers, nor among the Bedouin tribes. Nevertheless, it was about the Muslim travellers, and not the Western ones, whose incursions ended up in disaster. That is where the idea of travelling under the name of Ali Bey, as a Muslim and as an Abbasid prince, came from. This camouflage led to criticism from a society which still held certain reminiscences of the Holy Office, but Badía skilfully argued that it was but a mere disguise like the one used by many Christians, the assumption of a way of dressing not being linked to the profession of a particular religion. Once the religious obstacle was surmounted, the only thing left was to demonstrate the feasibility, to assure the success of his enterprise.

The travels of the British were sort of guarantee for his intentions, in particular those of mayor Houghton and Mr. Brown al-Dar Fur, the link between Egypt and Central Africa, and those undertaken to the sources of the Nile and Abyssinia by James Bruce. Next, the idea was to try to sell the product, the commercial side of his adventure.

By means of his journey, Badía would search out the best ways to expand Spanish trade in the African continent. Everything was set. He would travel first to London to acquire scientific instruments and also to be informed about the results of the latest British expeditions.

Then, he would enter Africa along the coast of the Strait of Gibraltar, pass through the Atlas Mountains and down to the Sahara to the Gulf of Guinea, cross Africa from this point to get to the lands of the Nile, and finally reaching the Mediterranean Sea through the desert of Libya, closing the full circle of his long itinerary.

At this point, the idea of providing the project with an overall political dimension came about. Ali Bey forwarded Godoy a new plan which included the conquest of Morocco, described the forces of the sultan and the benefits that this enterprise shall bring to Spain, as well as the real chances of success. But Badía came up against bureaucracy, while Godoy’s reply remained at a complete standstill. To this slowdown about the decision of his journey, the opposition of some academics, who feared that Badía might diminish their influence before Godoy, was added. The Academy laid down the condition that another person, one well versed in Africa, would have to accompany Badía. That was how the name of Simón de Rojas Clemente arose; he was a scholar specialized in mathematics, philosophy, and in Arabic grammar, and poetry. Besides, the future traveling companion of Badía enjoyed so-called “renowned prestige”.

This came in handy, for Godoy was aware of the imminent loss of the Spanish power in America, and he was interested in expanding the Spanish borders to a geographic space under British and French commercial hegemony. Badías’s project fit perfectly with the aims of the Prince of Peace. After some fallouts from the press of their day, and once he brought King Charles IV up to date on his intentions, Badía achieved the long-awaited financial support, and he departed to London via Paris in the spring of 1802.

We shall follow the vicissitudes of Ali Bey through his own handwriting, published in France in 1814, and in Spain in 1836. The task of making the reconstruction of an accurate and credible itinerary, with the letters and documents sent to Godoy, together with its correspondences in the story, proves to be a conflicting one, for it can be noticed that Domingo Badía was mostly interested in the scientific side of the journey rather than in the political one. In our days, the story is shown as a merging of political justifications and the story of the traveller’s adventures. In this state of confusion, between reality and dreaming, between legend and Ali Bey’s real experiences, is where its main attraction lies.

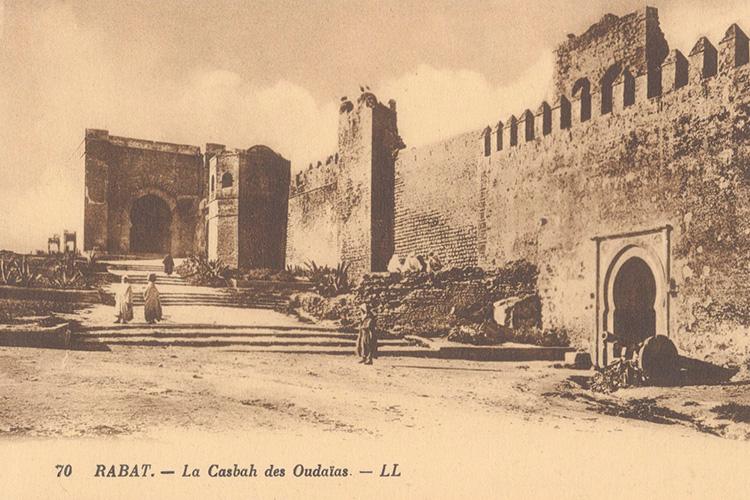

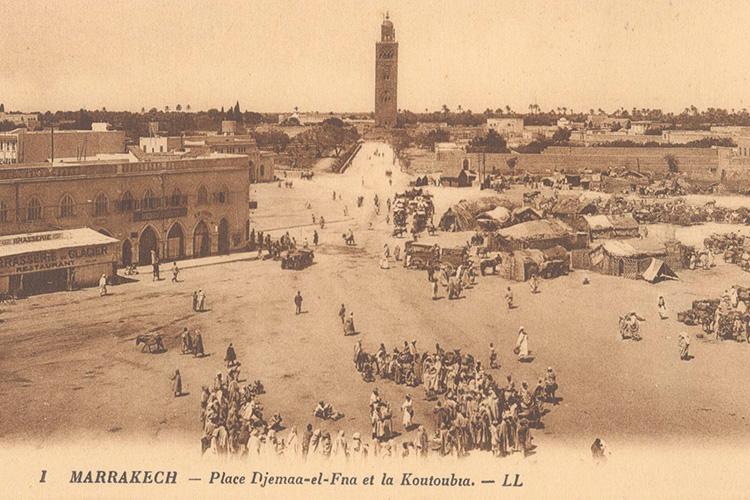

Ali Bey left his mark in Tangiers, on its mosque, where he made several reforms, among them a pillar at the entrance to the temple. He followed the sultan, who was attracted by his scientific knowledge, and Ali Bey was to foresee his tour through Morocco already featured. He travelled to Meknès and later to Fez. His friendship with the sultan’s brother took him to Marrakech, although not before going to Rabat first. His descriptions of the precepts, concepts and traditions of the Muslim religion are striking. He dissected it respectfully, but as a good rationalist he separated the wheat from the chaff, everything being conditioned, we guess, by those to whom the story is addressed, to a western reader. Ali Bey disregarded the Muslim teachers, whom he almost considered an impostor, and he underestimated the wise men of the mosques, to whom he enlightened with his knowledge.

His description of the circumcision ritual deserves to be included in one of the best pages on social anthropology. His narration includes passages of great literary quality, whose tradition has more of a direct link with the old stories of Arab travellers rather than with the western ones.

In Marrakech he was an honoured guest in a mansion in the suburbs on behalf of the sultan’s brother, while he was devoted to undertaking his geographic and scientific observations. It is in this place, in the idyllic framework of its garden, surrounded by storks and gazelles, that he decides to travel to Mecca, of which he informs the sultan. The Moroccan ruler gifted him two women and he organized a party in Mogador to persuade him to stay. Ali Bey accepted the two women so as not to arouse suspicion, but he did not keep any intimacy with them, and they came under his care. To follow through on his commitment to travel to Mecca, he had to put an end to the zeal of the sultan’s brother.

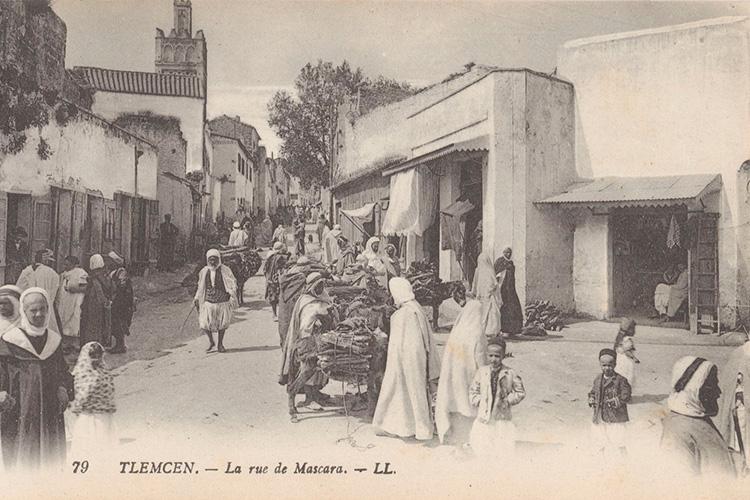

He departed from Oujda toward Algiers, but an unexpected insurrection stopped him in Tlemcen, where he reached an agreement with the rebellious tribes. He was finally halted by his “protector”, the sultan’s brother, and he had to shift towards Tangiers instead of taking the exit road Eastwards. The worst of his adventures starts here, as well as one of his most brilliant stories: the description of the way back to Tangiers. In the full desert area, during the month of August, following a strange route that did not pass through any city, he was overcome with weariness and thirst and, seeing death in the face, he was apprehended by order of the sultan and taken to Larache, where he was forced to embark. In that port, inexplicably even to the very Ali Bey himself, he was also forced to leave his entire entourage, including his women, as he was expelled from the country. Nothing was reported by Domingo Badía on this subject, about which he said he told he would clarify it later in his narrations, but he never did. It was more than two years he spent in Morocco, from 1803 to 1805, which he then linked with the account of the second part of his journey.

Ali Bey sailed to Tripoli, where he established friendship with the pasha while being under surveillance by the agents of the sultan, to indicate that the Moroccan ruler had started to become suspicious he was an imposter. He spent Ramadan in the capital of Libya so as to take a boat to Alexandria. This sea crossing shall take five months. The boat was lost in a storm when it was almost entering into port, and it was diverted to Cyprus. On this island our traveller remained two months, a stay whose description turns lyrical after his visit to the temple of Aphrodite. He finds himself there at a crossroad of cultures, a cosmopolitan syncretic place, something that delighted Domingo Badía. Some scholars of Badía’s work explain the stay in Cyprus as a sort of haven that Ali found to keep him away from the influence of the sultan of Morocco.

In 1806 he finally embarked for Alexandria. There he met with a city plagued with intrigues among the different local and colonial masters all seeking power, the place that was just a few years earlier the subject of the famous French expedition to Egypt. Ali Bey shall be more interested in Alexandria than in Cairo. Serendipitous facts, hazards, inherent in any adventure, appear once again in his journey: he met a brother of the sultan, who was to offer him a comfortable exile.

Ali Bey unfolds the best of his knowledge as a storyteller; and here is where the greater wonder of his account lies. He will not be able to travel to Medina, and so he will stop in Suez. Undertaking the third part of his journey to Holy Land, he visited every mosque, church, or synagogue he found along the way. What we have in Badía is a man without prejudices, interested in all kinds of cultures and beliefs and, above all, in the human being, despite the self-sufficiency that came from his aristocratic condition, a fact that did not diminish his liberalism.

After visiting Jerusalem, he shall depart to Constantinople where he will meet his friend from Granada, the Marquis of Almenara. In Turkey he travels throughout Anatolia, reporting places and people. His departure to Vienna shall put an end to his journey. Left behind were the years of adventure and the exciting testimony of Mecca, the height of his account.

Upon his return to the western world, he collided completely with a world in the hands of France. He is part of that constellation of enlightened men who worked for José Bonaparte. He was labelled as “Frenchified”, although he was only living up to his own ideals, those he considered could be best to serve Spain. In his exile in Paris, he came up with a new travel plan. Already a fifty-year old, Domingo Badía ̶ who had conducted interviews with Napoleon himself, well-versed in the wisdom of him ̶ started again to design yet another adventure. It would be his last, for he would fall dead in strange circumstances, mixed up in legend, when he started another trip to Mecca, always before that of Richard Burton.

In 1818, being well-known in France and in Great Britain for his published stories, one morning on August 31st, while he was in the middle of the desert, two servants went to awake him, he was found sleeping the perpetual sleep.

Some would say that he was poisoned by the spies of the enemy power; others would say disease was the cause. Yet the truth is that Domingo Badía continues to exist, as his image wearing a turban, his silhouette, is still marking any traveller who approaches the Muslim universe.

By Juan Luis Tapia

Journalist and writer.