The story of the Arma, the Andalusi diaspora in sub-Saharan Africa

By Fernando Ballano Gonzalo.

Before the Alpujarras rebellion took place in 1568, which was repressed by German soldiers commanded by Don Juan de Austria − stepbrother of Philip II−, some Muslims had abandoned the Iberian Peninsula before the fall of Granada, and others right afterwards. But many others, already second-generation Christians, established themselves in Morocco after the Alpujarras War, as well as in other places along the Mediterranean coasts of North Africa, whereas at the same time many Christian prisoners in the Berber lands rejected their religion and embraced Islam.

Among them was Judar Pasha, the Morisco from Cuevas del Almanzora (Almería), whose Christian name was Diego de Guevara. After integrating into Moroccan society, where he had arrived as a prisoner, he went on to occupy high-profile positions from the time he was very young, thanks to his brilliant actions in important missions. He was only sixteen years old when he was appointed pasha in the military area of Tangiers, a task he performed in such a brilliant way that the sultan appointed him caid of Marrakesh.

Ten years later, in 1578, he took part in the battle of Alcazarquivir between the Sultan and king Don Sebastian of Portugal, nephew of Philip I, who intended to conquer the Maghreb country. Many Spanish Moriscos, as well as renegade Christians, fought in the Moroccan ranks, where they were much acclaimed and better paid than in the Spanish army. Victory over the Portuguese, in whose ranks there were also Spaniards, added new captives, part of whom were also integrated into the askaria, the standing army of the Maghreb.

But Judar’s true epic starts in 1590, when Sultan al-Mansur assigned him to confront the powerful warriors of the askia of Gao, Ishaq II. Judar Pasha’s army, composed of 5.600 men who obeyed commands given in Spanish, had been dramatically weakened during the tough crossing of the Sahara. But they nevertheless won the battle, as they bored firearms, from which derives the name arma by which this community, mostly Andalusi, which populated the Niger River Curve, was known in subsequent centuries.

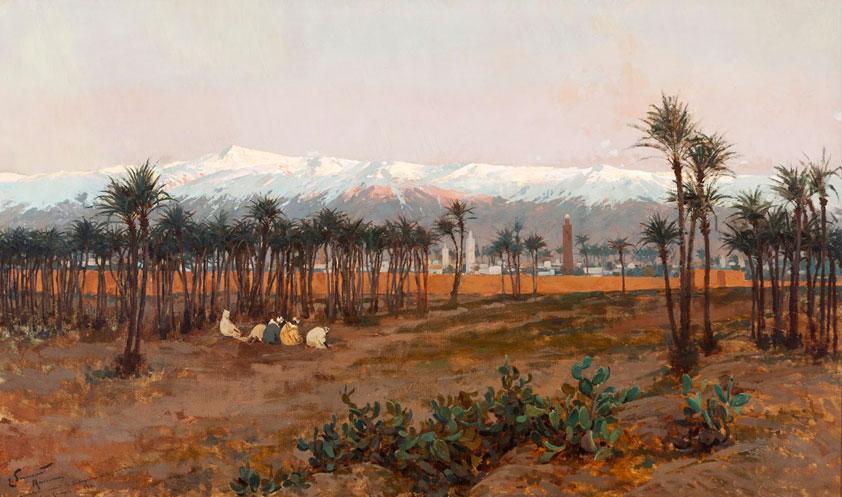

View of Marrakesh with the Atlas Mountains in the background, by Enrique Simonet, 1894.

Judar Pasha founded the pashas’ reign in Timbuktu after which he became the first ruler. Yet the intrigues in the Moroccan court led to his destitution, and he was back in the north of Morocco in the last years of the 1500s. He died in 1605, according to some sources during the struggles sparked by sons of the sultan to succeed him, while according to others he was executed by one of them for treason.

In 1606 the news arrived that Juder, participant in one of the sides which disputed the sultanate, had been beheaded. Both the Arma and the Songhay mourn him, and an annual celebration was dedicated in his memory, which also celebrated the return of Ahmad Baba in 1607. The following year Djenné rose up and in 1612 the Arma army faced the Songhai forces, but luckily, before engaging in the battle, they talked and negotiated a non-aggression agreement and kept the statu quo. In 1609 the Moriscos final expulsion from Spain took place.

Continuing intrigues

Between 1612 and 1622 six different pashas acceded to the throne and were executed by dissatisfied factions. . To avoid the continued intrigues, from that year it was determined the pasha would be appointed by a council or diwan comprised of military chiefs, officials, sergeants, treasurers and chiefs of the prominent families. A detailed protocol was established for appointments, as well as a procedure for dismissal. Although it was almost a military state, every garrison lived quite independently.

Morocco was obtaining fewer and fewer benefits from Niger. In 1620 the sultan decided not to help those who were not providing revenue collections, nor to appoint pashas. After the arrival in 1618 of 400 renegades, he did not offer reinforcements nor aid. Sent as cannon fodder, they had won, but they did not obtain the riches they expected and were left on their own. In total 23,300 men had arrived. . It was like a new al-Andalus, and despite many deficiencies, they had established −before nations claimed credit for it during the French and American revolutions− a system whereby rulers were appointed by governors.

Aerial view of Niger River.

The Arma State stretched along the Niger River, from Segú to Ansongo, one hundred kilometres south of Gao. News about being deprived of Moroccan aid was soon spread, and the Touaregs started to harass Timbuktu, the Bambaras attacked Segú and the Mandinkas took Djenné.

When they were left without gunpowder, they discovered that by boiling, filtering and then leaving the faeces of a local bird to solidify, they could get a product similar to soda. Then, by blending it with charcoal, it exploded like gunpowder, and in this way, slaves were put in charge of collecting the so-called excrements. They also had to substitute the thin skin of gazelle for paper.

But, despite the agreements for appointment and dismissal, intrigues continued. Some lasted just weeks in office. There was one who managed to remain only one day. Internal dissensions caused rifts into three divisions ruled by kakyas or generals. Cities and fortresses were divided up excepting Timbuktu, which was organized in neighbourhoods. The Fez division was comprised of Elches, as the renegades were called; the one of Marrakesh by Moriscos from al-Andalus who had always been Muslims, and the division of Chegara was joined by Mauritanians. Being the pasha of Timbuktu, and hence of the whole Arma State, became something symbolic with less effective power. Arma people were increasingly integrated into the native populations, but it was known who an Arma was and who was not. They were considered as Gakory, which means “white body”. Ahmed Baba died in 1627, and the tradition of studies was continued by his son Es-Saadi, who wrote Tarik Es-Sudan (Chronicle of Sudan, as this was how the area was named), which tells the history of Armas, although he left it incomplete upon his death in 1656.

The city regained some of its zenith and it is said that in 1638, doctor Es-Soussi from Timbuktu performed surgery on cataracts. In 1639 they suffered a terrible drought that lasted until 1642.

In 1645 a peace treaty was signed with the Songhay by means of which control of both the Peul (people from the area where River Senegal springs) and the Touaregs was achieved, compelling them to pay tributes. USome years later, the first pasha born in Níger, Alo E-Tilimsani, the son of an old pasha who ruled from 1612 to 1617, was appointed.

In 1667, in order to avoid fighting among divisions, a rotation was established among them when choosing a pasha, although there were still problems to find a candidate that satisfied everyone, and sometimes months of negotiations would pass before achieving it.

Pavilion and reservoir at the Menara Gardens in Marrakesh

Fever epidemic

Between 1657 and 1660 they suffered a major fever epidemic that caused many deaths, after which serious droughts followed. During that time, in Morocco the Alaouites monarchy came to power.

Many Arma stopped being soldiers and undertook crafts such as tailors and embroiderers.

In 1689 Moroccan sultan Muley Ismael wanted to renew tax collection and commerce under conditions largely unfavourable for the Arma, but he failed and had to settle for more reasonable terms. In the early 18th century, a wall enclosing the city was built, with four guarded gates, and to some houses were added supplementary floors to enlarge their capacity and, at the same time, upgrade defence.

Many were the pashas who were notorious for corruption and larceny. In 1716 ruled Mansour Korey (Mansour the White) who was so called so due to his uncharacteristically fair complexion, albeit one hundred years of crossbreeding had been taking place. He was corrupt and cruel in the extreme. He organized a private army of one thousand five hundred slaves, who were called legas (hitmen). He was devoted to stealing from ordinary citizens for their master’s gain, who, in his turn, continued imposing new and abusive taxes. He called upon the Arma to solve a personal matter with the Touaregs, who had stolen several horses from his own stables. The army refused and, later on, together with the population, it rose up against him. In 1719 he had to flee in secret, leaving behind most of his fabulous wealth.

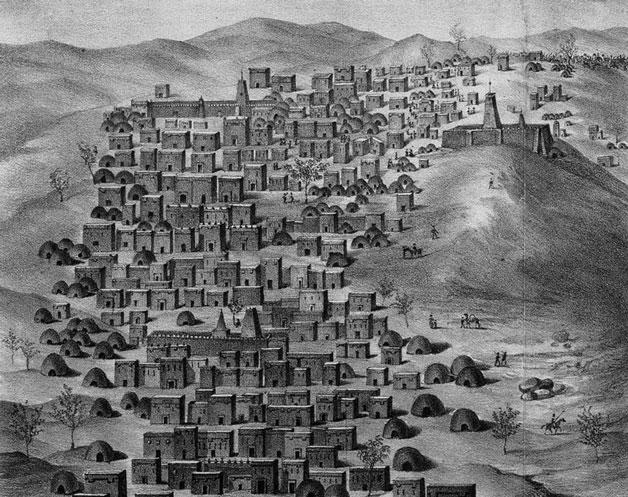

Timbuktu in 1830.

Although the Arma were integrated in the Koterey group −or older age groups of the songhai culture− they also had their own −or Alyinsi−, who were obligated to provide mutual help when needed and imposing their sanctions when the rules of the group were broken.

From 1730 on, the division belonging to the descendants from the Mauritanians rose up against the other ones. Their slaves abandoned them and were defeated, went someplace else or were subjected to the triumphant divisions. Among the very Arma, despite being the dominant caste, there were many social differences, and some went through true distress to survive. In 1737 they suffered torrential rain hailstorms and even snow; as a sign of the crisis, cola nuts grew from ten cowrie shells per piece to cost two hundred.

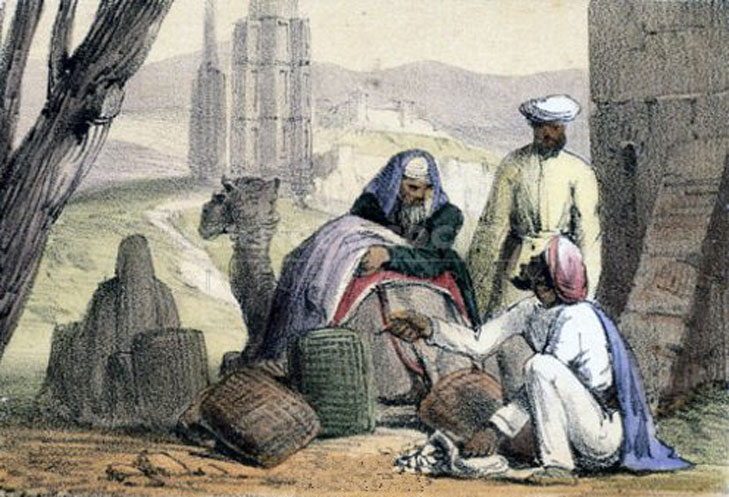

Illustration showing a group of African traders exchanging goods and paying with cowries.

They were increasingly harassed by the Touaregs, who often visited the city taking everything they wanted. In 1737 all the Arma from the region, together with the Songhai, gathered together to make war upon them in Toya, close to Timbuktu. They failed and had to retreat to the city, waiting for a siege that never took place, because they attacked the cities of Djenne and Gao, which were left unprotected, instead.

They had to surrender, and they proceeded to pay taxes to the nomads, which reduced commerce even further. A severe drought that lasted from 1741 to 1744 brought famine and plague all along the region. The cost of a cup of millet grew from ten cowrie shells to ten thousand in a few years, and for this reason it had to be paid with gold. Ostriches, which were only used for their feathers so far, disappeared. On top of that, Timbuktu was struck by an earthquake in 1755, and in 1770 the city suffered a hard siege by the Touaregs for almost one year, causing the death of their boss at the hands of the Arma. In 1790, the Bambara finally took over Timbuktu.

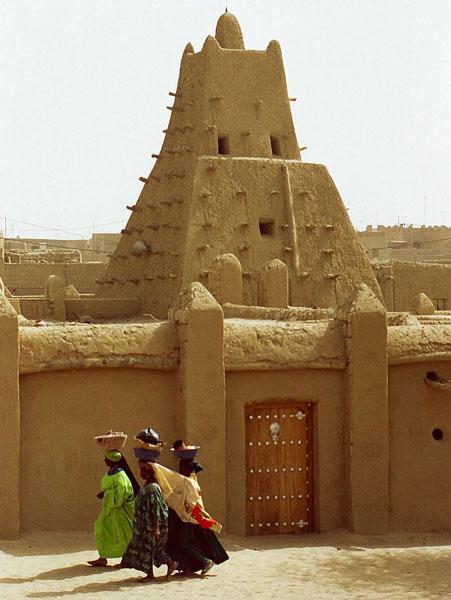

Scene of daily life around the mosque of Yinguereber, built by the Granadan architect Abu Hq el-Sahel in 1327.

The evolution of Timbuktu in the 19th century

En 1826 Amadou, a fanatic Peul, took over Timbuktu, although he respected the pasha system of the Arma. In 1831 the Arma, under the command of the pasha Osman, rebelled against Amadou with the help of the Songhai and the Bambara. After successive collapses, pashas ceased to be appointed.

In 1880 the French started to penetrate the continent following the axis of Senegal River. They later continued along the course of the Niger River by mean of steamboats that they carried dismantled to the river shores.

In 1894 they occupied Timbuktu to defeat the Touaregs. They turned the administration of the city to the Arma, but they took possession of the treasury, which had been carefully guarded by the pashas and the alkaidis despite difficult times of scarcity. The so-called treasury consisted of the banners used in the battle of Tondibi, the sword that belonged to a sultan, a pickaxe in gold, a rosary with beads of coral, a parasol and dozens of carpets and cushions. The French built a fort, Fort Bonnier, that they used as a headquarters to continue the expansion towards the southeast of Africa. They proceeded until they met the English, who were going up along the coast of current Nigeria, for after the Berlin Conference it was necessary to occupy territories to have rights over them.

Slave traffic was prohibited, but they established native forced labour. In countries like Liberia and Sierra Leone liberation was already in effect but unfortunately, freed men became themselves top exploiters, as they considered the natives savages and inferior.

Mosque of Djinguereber in Timbucktu.

The First World War meant the mobilisation of the natives, who entered the regiments of Senegalese sharpshooters, despite the fact that they came from all of French West Africa.

After independence in 1958, the French left the administration in the hands of the Bambara, the dominant ethnic group. In order to avoid tribal problems, every aspect related to segregation was prohibited and even to register the Arma.

From 1972 on, severe droughts forced the people of the region of Timbuktu to migrate to the south, fleeing from the desert.

In the eighties the region was attacked again by the Touaregs, and the inhabitants of Gao had to organize groups of self-defence as is precedent centuries.

Eminent Spanish philosopher and essayist Ortega y Gasset recalled in an article published in 1924 in the newspaper El Sol, the deeds of these ancestors while wondering why it had been forgotten. His words did not echo much until in the 80’s a group of scholars from the University of Granada, including Manuel Villar Raso (R.I.P) and Amador Díaz, revitalized the issue that has borne fruit with the help of the preservation of the archives of Timbuktu.

By Fernando Ballano Gonzalo.

Journalist.

.

Condensed online version of the printed article published in 2006, (issue number 26) of the magazine El legado andalusí. Una nueva sociedad mediterránea (2006)