The alhóndigas of Granada

By Ana M. Carreño Leyva

El legado andalusí Andalusian Public Foundation

All that remains of the intense commercial activity that took place in Granada in Nasrid times is the Yadida alhóndiga. Known as the Corral del Carbón (Coal Yard), it is the only one that is preserved in Spain. Today it hosts, among other cultural institutions, the headquarters of the Fundación El legado andalusí (The Legacy of al-Andalus Foundation).

Medieval Granada was a paramount hub for commerce that attracted merchants from throughout the Mediterranean region. Granada’s products enjoyed enormous prestige, above all textiles, agricultural products and ceramics, together with manufactured of luxury goods, such as silk and other precious fabrics, that were famous worldwide. Commercial activity conferred an extraordinary dynamism on the capital of the Nasrid Kingdom. Both Yusuf I and Muhammad V supported this sector by providing alhóndigas (storage yards which also accommodated merchants) and other buildings aimed at commerce, and patronage of infrastructures such as transport routes and secondary ports like that in Salobreña. But actually, the real boost that this commercial activity faced at an international scale was possible thanks to the intervention of the Nasrid state, with the involvement of the political and economic elites.

Egyptian doctor and merchant Ibn al-Basit, who visited Granada and was received by sultan Muley Hassan in 1465 and 1470, tells us in his account of the “atmosphere of its streets crowded with weavers, jewellers, potters, leather craftsmen and weapons manufacturers” . These items found export markets in Castile or in the whole Mediterranean area through the ports of Málaga and Almería. Ibn al-Basit also made interesting remarks on the popular ceramics from Granada, like the one he refers to as a type of red clay with which were made very light pots for water, which added an extraordinary flavour and beneficial properties to purify the blood.[1].

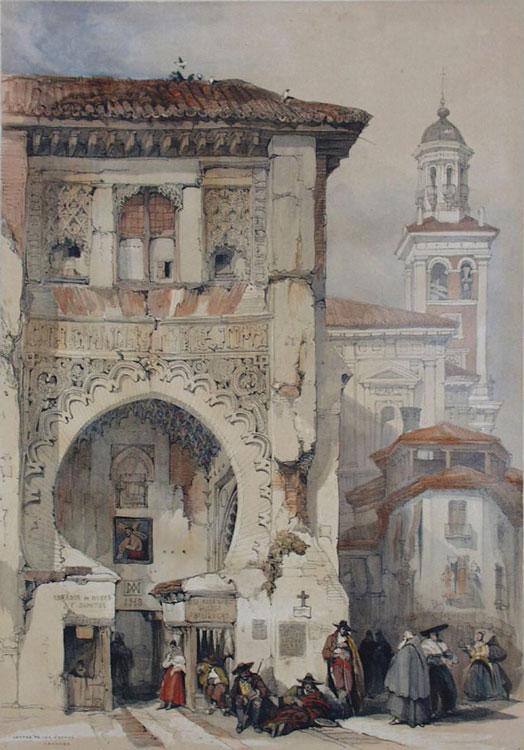

It is easy to imagine the hustle and bustle in downtown due to the frantic commercial activity; however, few are the related places that are still standing today, and others we only know their exact location and from others, we unfortunately have just the testimony left by artists who depicted them. Their works brought us close to that Granada of old, although as if though a portrait veiled by the deceptive fidelity of imagination and the creative mind. It was the Romantic travellers who particularly illustrated the pages of history, of that missing heritage, by projecting an image of melancholy upon of Granada whose old splendour was but a dull shine in its derelict buildings.

[1] Álvarez de Morales, C. “Abd al-Basit visita el Reino de Granada. Revista del CEHGR núm 26. (2014)

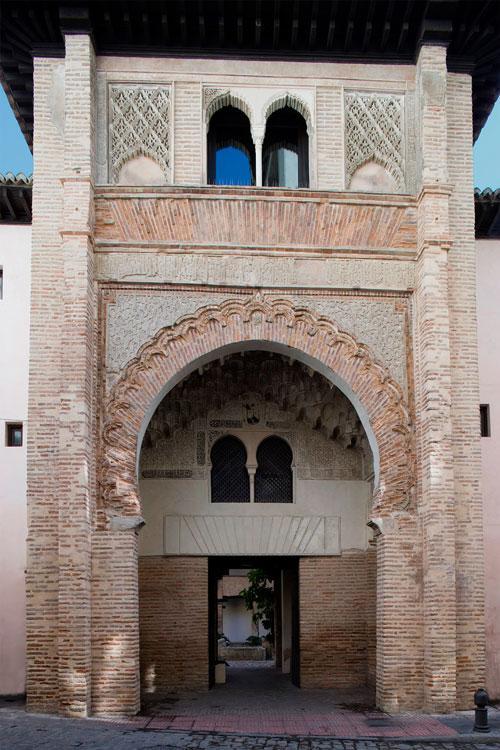

Inside the arch in the façade of the Corral del Carbón decorated with muqarnas.

International Commerce

However, already in the 10th century, Zirid King Abdallah tells us in his Memoirs that Madinat Ilbira, and later on Madinat Garnata (Granada), controlled the commercial traffic in the region, which counted with an important commercial structure. Actually, in the early 13th century, having consolidated the politics of the Kingdom of Granada, the first trade agreements with foreign powers, like Genoa were signed. These trade agreements were reinforced by the proximity of Granada to the ports of Málaga, Almuñecar or Almería, in a way that a new scope of commerce increasingly expanded to other areas as Catalonia, Venice, Florence, Majorca, Aragon and the North of Africa.

According to Christian documents, there were at least 14 alhóndigas in Granada. This designation leads us to believe that judging by the number of them, they took the nomination from the Arabic translation of al-funduq, which also gives name to the Spanish popular accommodation known as “fonda”.

These properties, owned by the Nasrid royal family, as well as the oil and flour mills, public ovens, shops and baths, were taxed under the so-called “hagüela” [2] (hawala), the levy, which refers to the credits of subrogation or transfer according to Islamic law. As shown in the lists that appear in the Nasrid habs (waqf),[3] almost all these alhóndigas were located around the Bibarrambla and Zacatin neighbourhoods, although there were others in the gate of the Albayzín, next to the mosque of that quarter −today’s San Salvador− the Cuesta (Hill) de la Alacaba and on the current Plaza Nueva.

However, in Granada, the principal buildings aimed at the service of commerce were three: the alhóndiga Jadida (Corral del Carbón), the Zaida, and that of the Genovese.

Of these three alhóndigas only one has survived; the only one in Spain: the Corral del Carbón (the Coal Yard), which is in a perfect state of conservation. The story of its survival describes the vicissitudes of a city that was first Moorish and then became then Christian, which from being adorned with the most beautiful Islamic constructions was decked out with opulent Renaissance exuberance and embraced a cluster of styles marking the keystones of its existence.

[2] Peinado Santaella, Rafael G. “El patrimonio real nazarí y la exquisitez defraudatoria de los principales castellano”. Medievo hispano: estudios in memorian del Prof. Derek W.Lomaz. 1995.

[3] Inalienable charitable endowment under Islamic law, typically involving the donation of buildings, plots of land or other assets to the sustainment of institutions of a religious, social or godly character.

Today known as Corral del Carbón, the alhóndiga al-Jadida, or the New, was built by Nasrid King Yusuf I between 1300 and 1332. Although it was a gift for Madinat Garnata (the city of Granada), it belonged to the Nasrid Queens. Many documents prove this, among them the letter of consent subscribed by the Marquis of Ureña, with the participation of the Catholic Monarchs in 1493, precisely related to al-funduq al-Jadida: “all properties, and lands, and heritage, and oil mills, and bread mills, and ovens and shops, and inns and parlours and saloons, and baths and whatever real state that they may have, and every one of them, in this city of Granada and in its lands and province, and in Motril and Salobreña and in other parts of this kingdom of Granada”.[4]

[4] Simancas. Negociado de mar y tierra, nº 1315 (Colección de documentos inéditos para la historia de España, tomo XI (Madrid 1847), pp. 543-544)

The Alcaicería.

The location of the Jadida alhóndiga was superb given its proximity to the Alcaicería, al-qaysariyya. This was a souk which closed its doors by night to provide security, since it hosted expensive luxury goods. Customers were mainly from abroad, and this luxury commerce blossomed in Granada in the lower Middle Ages thanks to the diverse treaties subscribed among the Venetian Republic and the Kingdom of Granada. At the time, the Jadida alhóndiga stood in the left bank of the Darro River, where a bridge connected both banks, the so-called the New Alhóndiga Brigde, and later on The Carbón (coal) Bridge.

These facilities hosted small merchants; the well-off ones were lodged in different places to stay where they did not have to share the same space with the animals, thus avoiding unpleasant smells. The building had two floors, where rooms were distributed, being accessed through two staircases, from which only one has been kept. Pack animals were roomed on the ground floor of the building, where goods were also stored. In the centre of the porticoed yard, a basin fed by running water helped with watering the animals as well as other washing needs.

This alhóndiga was mainly dedicated to the commerce of cereals, wheat above all, and following the lead of other alike establishments lacked windows, and access was only possible through a single entrance in the main façade. The building manager lived in a house above, in order to watch through an ajimez, -a window divided into two parts by a central column located in the entranceway-, who went in and out of it.

The beautiful design of the Corral del Carbón brings us an echo of its relatives from other lands: the khans, iwans, fonduqs, or the legendary Sasanian caravanserais spread through the remote mercantile routes in the East, like the Silk Road.

To the Left, the façacade of the Corral del Carbón as it looks today, after its latest restouration carried ou in 2006. To the right, main portal of Sultan Qaytbay caravanserai, built in Cairo in 1481.

The main façade, as beautiful as it is imposing, is something quite unusual in this type of constructions in Western Islam. It showcases a small-scale display of the decoration motifs at the Alhambra, the most outstanding elements of the Nasrid style: muqarnas, plasterwork, lobed blind arches… It is a body basically rectangular which protrudes from the building, 10 metres high, in which the entrance is inserted, facing the bridge crossing up to the Alcaicería. In the façade opens a large horse-shoe arch, with a festooned moulding made of brick, and plasterwork decoration in its cornerstones. In the horizontal moulding that limits the alfiz (moulding used as a decorative element to enclose the outward side of an arch) appears an inscription in Kufic characters whose translation is: “God is unique, God is eternal, He begets not, nor was He begotten, nor has He paragon”.

After the Catholic Monarchs conquered Granada, they proceeded to the division of the properties of al-Andalus’s among the church, the nobility and the military officials who contributed to the victory in the conquest of Granada, among others. Thus, in 1494, the Catholic Monarchs gave the Corral del Carbón ownership to their “mozo de espuelas” (groom who walked by the king’s horse as he left the palace). As we can read in a document: “ you will own by our gist the Casa del Alhóndiga gedida (the House of the Alhóndiga Gedida) located in the city of Granada, were bread is sold in grain, and you will be able to host in there whoever coming to such city and keep for yourself whatever benefits or rights derived from it, as it have been done and is customary to do in the times of the Moor kings and queens of Granada, to whom first belonged such house and is now ours when we won such city…” The donation of property took place in the year 1500 as recorded in a document dated 20 December of the same year. The document reflected that “there was a bridge that led to Zacatín Street”.

The river Darro at it passes under the Puente del Carbón, next to the alhóndiga of the same name, in 1834. Engraving by David Roberts.

When the owner died, the property was auctioned and became a point of sale for coal and later on a comedies theatre protected by the Golden age of Spanish theatre, which lasted until 1593. Today, many activities such as concerts, theatre performances and others which benefit from the fine acoustics of the site are still hosted here.

The economic downturn that Granada experienced in the 16th century after the expulsion of the Moriscos, the real architects of Granada’s Industry, such as agriculture, textile production, ceramics and some many other productions, turned the Corral del Carbon into a tenement house. Here families of humble condition found shelter. They inhabited their rooms and used the courtyard to carry out activities through which they earned their living as crafts as artisans. The ground floor was also used as a stable and storage area. It was also for some time a customs clearance house, and a point of sale for coal.

In the 17th century, Hernández de la Jorquera, in his work Anales, recorded that “for the vast majority of people, the building, both before and after, seemed old and broken, ugly and devoid of interest because of being a property of the city, the reason why in the big mass of the Corral del Carbón was not built a big manor, despite being in the best place of this city and its main commercial area […]” During that century, the alhóndiga served as a neighbours’ courtyard, a warehouse and stock house of goods and a stable for the coal vendors, as well as a customs and public weighing-house, activities carried out simultaneously together with commerce and the storage of cereal. The activity that ceased after the conquest of Granada was that of accommodation, and the products which were normally traded were the imported ones, like cereals, scarce at those times in the Iberian Peninsula.

By the end of the 19th century, the Corral del Carbón, by that time in private hands, was about to be demolished, despite having been declared National Historic-Artistic Monument in 1918. The huge interest of the building, given its unique position in the very heart of the city and the high cost of the lot, pushed some to propose other solutions like the preservation of the façade only, as the sole monumental element and the demolition of the rest, as according to them for its lack of interest, for, moreover, it was also in almost in a total a ruined state.

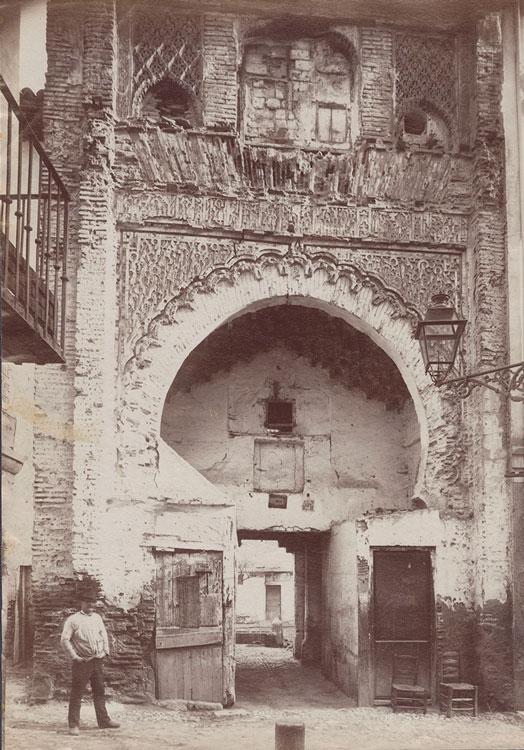

To the left the main gate of the Corral del Carbón as described by David Roberts in the 19th century. To the left, a photograph from the beginning of 20th century.

Yet, there were people, like the great architect Leopoldo Torres Balbás, the architect-curator of the Alhambra, and Manuel Gómez Moreno, among others, who knew how important the preservation and conservation of historic heritage was. Their eagerness, together with that of people who worked on the elaboration of a never-ending list of reports, saved it from demolition.

In 1928, the architect-curator of the Alhambra secured the purchase of the Corral del Carbón by the Spanish state, for a value of 128,000 pesetas (€769, circa $769 in current US $), from the funds corresponding to the Alhambra’s admission tickets, a method also employed for its restoration and of other Andalusi monuments of Granada. A year later, first reports to start the works in the building urgently, for its was in a state of imminent ruin nevertheless thirty-five humble families which had adapted it or destroyed it to turn it into a place to live.

The once-upon-a-time funduq was now an unhealthy neighbours’ courtyard; they had installed kitchens and, to allow the stoves vent smoke, floors and walls, and even load-bearing walls were broken. Partitions in the gallery were also made and the yard was used to carry out domestic works.

Torres-Balbás was in charge of its restauration, and the extent of the structural strengthening took him another year, until 1930, when he finished. It was then when the beautiful baseboards which decorated the upstairs rooms that hosted the clients were found.

In 1992 the building was restored again, following other works to correct flaws, until a final and superb intervention was done in the façade in 2006 by experts Lola Blanca López and Lourdes Blanca López.

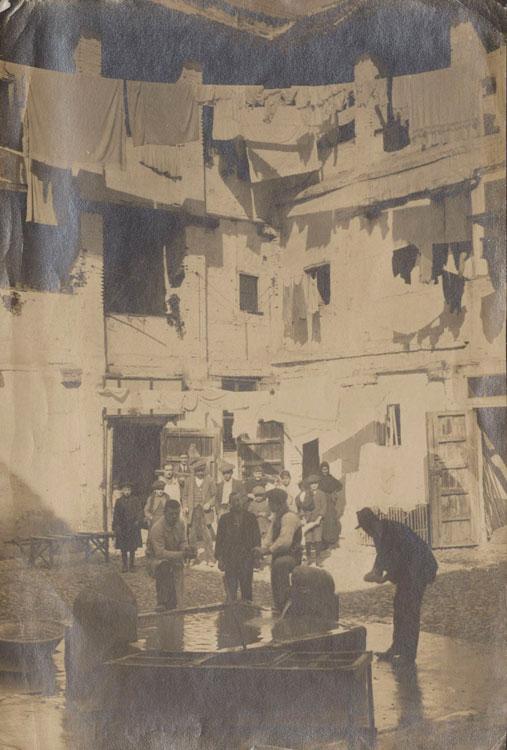

These images show the daily life activities carried by the inhabitants of the Corral del Carbón before being evicted to undertake the restoration works.

It was precisely the spot chosen to build the cathedral and the Royal Chapel, hence the demolition of a great deal of places was necessary. It was precisely the spot chosen to build the cathedral and the Royal Chapel, hence the demolition of a great deal of places was necessary. Further down, in the current Puerta Real, where the famous literary coffee shop, Café Suizo once was, there stood another alhóndiga, the Zaida. Known as the Christian’s alhóndiga, to whom its use was restricted because of the segregation that the Catholic Monarchs tried to impose after the conquest, it was a market where food products were sold, like olive oil, cheese, honey, raisins, dried figs, fruits and vegetables in general. According to facts that the excavations of 1992 brought to light, it was built between the 12th and 13th centuries, and its layout was almost identical to the nearby alhóndiga al-Jadida, the Corral del Carbón.

We also know that there were food stores, −where fritters and meals were sold− to provide food to merchants and people who attended the mosque for prayer. This was also the environment where the madrasa of Granada, the Yusufiyya, the first public university in al-Andalus, was funded by Yusuf I in 1349; today it is owned by the University of Granada, and it continues to follow its purpose as a centre of culture.

The alhóndiga Zaida had a great importance due to its location. It was in the vicinity of the two other alhóndigas, and most importantly, in a most privileged site as it was the square where the main mosque was. In addition, it was next to Alcaicería, a place for the sale of luxury items, where sugar was sold, which was very precious in the Middle Ages and considered the height of exotic luxury. A long street named Zacatín (al-Saqqatin) was the backbone of the area, which starts in current Plaza Nueva and finishes in Bibarrambla Square. Both the Arabist Seco de Lucena, as well as the historian and archaeologist Manuel Gómez Moreno, agree that, according to the sources consulted, the street was, both then and now, an eminently commercial street, although in Nasrid times it was mainly occupied by silversmiths, lingerie shops and rush weavers, etc. Torres Balbás, for his part, states that the name of the street in Arabic (saqqatin) is due to the existence there of many old-clothes sellers.

Building in Puerta Real, there stood another alhóndiga, the Zaida, too known as the Christian’s alhóndiga.

The flow of foreign traders made necessary accommodation and places to safely secure goods. This was the case of the alhóndiga of the Genoese, who were Granada’s best customers. Here, they obtained the esteemed silk from Granada and other sumptuous cloths, among many other luxury goods sold at the Alcaicería. Other Italian merchants, the Tuscans, also sourced their textile industry with the silk from Granada, which the Catalonians sought to monopolize at the beginning of the 15th century. The alhóndiga of the Genoese was located quite close to the site where the Puerta del Perdón (Gate of Forgiveness) of the cathedral was later built. In 1492, once Granada passed into Christians hands, this popular alhóndiga became a prison, according to German doctor and traveller Hyeronimous Münzer who visited the city two years after its conquest. The street where it was located was named as Cárcel Baja (Lower Prison), and it was demolished in the 1940’s.

Granada held the largest Andalusi monumental heritage in Spain. The process of demolition, or adaptation for other uses, of the Arab buildings started in the 15th century: mosques and major palatial residences gave way to churches and convents, when they were not passed down to the different aristocrats who took part in the conquest of Granada.

It was in the 19th century when the largest urban reform that the city has ever known was undertaken. It was required to widen and build new roads and to rearrange the urban layout to accommodate new neighbourhoods and boroughs. The tunnelling of the Darro River made the many and picturesque bridges useless, which vanished as many other beautiful spots, surviving only in our memories, in the historical records or in the testimonies left to us by the artists.

By Ana M. Carreño Leyva

Fundación El legado andalusí

|

BIBLIOGRAPHY Álvarez de Morales, Camilo. “Abd al-Basit visita el Reino de Granada. Revista del CEHGR núm 26. (2014). Torres Balbás, Leopoldo. “Alcaicerías”. Al-Andalus nº 14 (1949). Torres Balbás, Leopoldo. “Hispanomuslim cities” Madrid. City Museum. Ministerio de Asuntos exteriores. (1951). Seco de Lucena Paredes. Luis. “Arabic writing of Granada University” Al-Andalus, vol. 35-3 (1970). Gómez-Moreno González, Manuel. Guide of Granada. …, op. cit., pág. 184. Madrid 1892 Jiménez Roldán, María del Carmen. “Del funduq a la alhóndiga: un espacio entre el emirato nazarí y el reino de Granada (s. XV-XVI)”. Al-Qantara IX 2, julio diciembre 2019. Jiménez Roldán, María del Carmen. “From Funduq to Alhondiga: a Space between the Nasrid Emirate and the Kingdom of Granada (15th-16th century)” Al-Qantara IX 2, July December 2019. Henríquez de la Jorquera, Francisco. Anals of Granada : Description of the Kingdom and city of Granada; Chronical of the Reconquest (1482-1492); events that took place from 1588 to 1646. Granada: Universidad de Granada [etc .], 1987. Fábregas García, Adela. « Designs of ceramic sugar bowls in the market of Granada”, “Arqueología y territorio medieval, 2 (1995), pg. 225. De la Obra Sierra, Juan María. Catalogues and protocols…, op. cit., pág. 193, núm. 291. Villanueva Rico, M.ª del Carmen. Habices…, op.cit., pág. 30, núm. 28 y 29. Arroyo Pérez, Encarnación. Pérez Torres, Carmen. Fresneda Padilla, Eduardo. López López, Manuel. Peña Rodríguez, José Manuel. «Urgent archaeological excavation at the Zaida alhóndiga in Puerta Real – Calle Mesones Street. (Granada)». Anuario Arqueológico de Andalucía/1992, t. III, Cádiz, 1995, págs. 279-283, espec. pág. 283. |