Münzer, a journey through Spain in the sixteenth century

PART I

In the year 1495, just three years after the Catholic Monarchs had conquered Granada, a German traveller, Doctor Hieronymus Münzer visited Granada. He left us an important chronicle about the newly Christian city.

Travelling has always occupied a privileged position among the activities of human beings, driven traditionally by the desire to know different worlds. In the early Middle Ages, most of the Roman roads, which were already deteriorated began to disappear. Many of them remained, but the truth is that most of them remained in a poor state. Weather and vegetation caused damage, as did the lack of a proper conservation, which were, among others, the causes that caused a worsening in their condition. Later on, due to more sophisticated construction techniques, land routes were gaining in quality with the passing of the centuries. This factor, combined with more advanced Equipment and transportation carts designed to reach higher speed, encouraged people to travel more.

Yet, moving from one location to another in the Middle Ages was never easy. Travelling, apart from entailing serious risks, required one to face a wide variety of situations that, as if that were not bad enough, were necessary to be solved under very poor conditions. Because to the discomfort of the transport options, other inconveniences were added like, for instance, having to defend oneself from the bandits, or having to pay tolls in certain transit areas.

And yet, travels in the Middle Ages were very common, mainly in its final stages. There was a particular interest in trading with people from other cities and strengthening bonds among different countries, which led to a seamless to-and-fro of caravans and embassies. Religious pilgrimages destined to foreign lands were equally frequent and finding people with a restless spirit to obtain information of the known world. Otherwise, we must think about the regular and persistent epidemics that often whipped up the populations, which constituted a serious threat to its inhabitants, who were in most cases forced to leave their places of origin to seek greater safety.

Screenshot of a fragment from a virtual reproduction from Ernst George Ravenstein’s facsimile created in the 20th century, improving the readability of Martin Behaim’s globe produced in 1492-1493. ©Instituto Geográfico Nacional. Servicio de documentación.

As it has happened throughout History, under the umbrella of these travels arouse a rich and extensive literature, which even though it was mainly attributed to the guild of writers, it was due in many cases to the inspiration of people who were not apparently related to the world of paper and ink. Regardless of whether it was addressed to some personalities in particular or to a broad public, under this type of writing underlays a certain proclivity to tell about autobiographical experiences with which the author, independently of his academic formation, just expected to entertain, to raise scientific questions or to develop a literature combining both things. Typically, these notes were recorded daily and put in order so as to, once the journey was over, draft the material that would result in a book. The resultant work, among other contributions, provided historical and geographical data about the sites visited by the traveller, as well as the social and political information on the people he reached. In the same way, the traveller used to reflect the feelings he experienced when he started an adventure and the particular conditions and situations that he needed to sort out when he arrived in new spaces and when he made contact with different communities.

In Hieronymus Münzer, like did many other characters ̶ who invested time and energy in undertaking a long journey ̶ some of these forementioned elements, factors, purposes, risks, obstacles, and constraints converged.

In Hieronymus Münzer, like did many other characters ̶ who invested time and energy in undertaking a long journey ̶ some of these forementioned elements, factors, purposes, risks, obstacles, and constraints converged. He came into existence in a date yet to be determined, in a wealthy family from Feldkirch, a small town in the Austrian province of Vorarlberg. The town, located in a frontier area rich in forests and mild in climate, was in the western-most area of Austria and belonged to an administrative section which formed in other times a region with Tyrol, from which it is physically separated by Arlberg, the well-known mountain pass of the Alps. According to the dates which reflect some of his activities, we can assume that he was born in the year 1460, a time when the Austrian domains were divided. Frederick III and Albert IV respectively shared the Lower and Upper Austria. Then, not much time later, Maximilian I, son and heir of Frederick, Philip “El Hermoso” (“The Handsome), and hence, grandfather of our closer Charles V, brought to pass a first phase of greater regional cohesion. Emperor Maximilian was a huge advocate of sciences and arts, and he was very interested in promoting the new humanist culture, always knowing how to surround himself with great scientists and men of letters. It appears that those were precisely the concerns that led him to ask Münzer personally to address a letter to the Portuguese monarch John II, requesting him to taking part in a maritime endeavour like that of Cristopher Columbus. Thus, we planned to reach the Asian coast via the Atlantic Ocean. At the sight of his intellectual drive, and once Maximilian I saw how queen Elisabeth had supported the famous sailor, and having been informed the triumphal way he was welcomed in Barcelona by the Catholic Monarchs, it would not be surprising that Columbus’ success fostered in him a desire to imitate his deed. The important thing was to find a person who could oversee the details of the operation. And it is believed that it was Münzer who was selected.

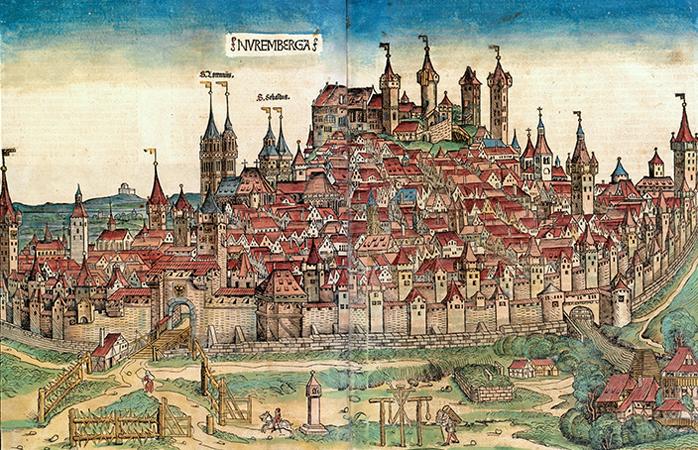

Nüremberg in the Liber Chronicarum (1493).

We have made assumptions before of the Austrian traveller’s date of birth. To this effect, we take as reference the year 1479, the moment when we know that Münzer obtained his doctorate in Medicine. His graduation took place at the renowned University of Pavia, in the banks of the Tesino River, after having furthered studies in this same Lombard city. Nevertheless, months later, when he had his doctor degree in Medicine under his arm, when he was not yet twenty years old, he moved to Nuremberg, a city that soon received from Italy in a direct way the seeds of Renaissance civilization.

It is quite probable that it was here that he met he German historian Hartmann Schedel. He, after having studied Medicine in Italy, had returned to his hometown not only bearing his degree in Medicine, but also with a high interest in classical antiquity, and with a certain talent to depict the notable things he had seen in the Italian cities. It is worth mentioning the name of this famous humanist because at the Munich Library is kept a miscellaneous manuscript ̶ the Codex Latinus Monacensis 431 ̶ which having belonged to Schedel, contains a section with more than two hundred long folios corresponding to a work from Münzer. The librarian from Munich, A. Schemeller reported this and other works from the same author in the 19th century. Then, soon after, Friedrich Kunstman would decide to publish one of them, together with some scattered fragments from Münzer’s work. The itinerary had taken place in the years 1494 and 1495, and its results were later published under the title of Itinerarium sive peregrinatio per Hispaniam, Franciam et Alemaniam (Itinerary of the pilgrim through Spain, France, and Germany). It was the prominent multidisciplinary writer Arthur Farinelli who, after consulting the manuscript in Munich, was the one who insisted in advisability of its publication. The Italian professor’s praises must have weighed on the spirit of the prominent Hispanophile Foulché-Delbosc, and he hosted part of the account related to the Iberian Peninsula in the pages of the Revue Hispanique the publication he both founded and edited. The work of this edition was also carried out by Ludwig Pfandl, who published it in 1920 under the title of ltinerarium hispanicum. Four years later, the scholar Julio Puyol presented in the Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia the translation into Spanish of those fragments entitled Viaje por España y Portugal en los años 1494 y 1495. Subsequently, in 1951, José López Toro would be in charge of releasing a new Spanish version.

Doctor Monetarius had to leave Nuremberg in 1484 due to an epidemic of plague hardly five years after he started to practice medicine in this city. It was the year 1484. He departed from there to Italy, where he lived over a decade, returned to Nuremberg only to leave in 1494 because of new outbreaks of plague.

This time he departed accompanied by two young men who were friends from the city, Nicolas Wolkenstein and Gaspar Fischer, together with a friend from Augsburg named Antonio Herwart. They started the journey on 2 August, travelling together through Germany, Switzerland, France, Spain and Portugal. Upon returning to his country, the Austrian doctor had still time to outline all he had compiled during the tour. Thirteen years later, on 27 August 1508, Jerome Münzer died in Nuremberg, at the age of almost fifty. Before passing away, he was acquainted with the death of the famed German geographer Martin Behaim, which had occurred one year before in Lisbon, in July 1507. We mention this fact because it was with this famous navigator and friend of Columbus, with whom Münzer had the opportunity to take part in the construction of the terrestrial sphere, to whom Behaim owes his indisputable glory. It is precisely his participation in the construction of this famous globe, as well as his collaboration in the Latin edition of the Liber Chronicarum by Hartmann Schedel, that makes it possible to include Jerome Münzer among the renowned geographers from Nuremberg.

Martin Beheim’s globe, known as the Erdapfel (“aple of the Earth”) was produced between 1492 and 1493, being considered the oldest one preserved. The Americas are not included since Columbus returned from his trans-Atlantic voyage a year later. It is preserved in the German National Museum in Nuremberg.

Because, in effect, Münzer can be considered a humanist expert in geography and astronomy. It should be pointed out the interest that both Maximilian, as much as the very Austrian doctor, showed toward the maritime adventures that took to the East through the West. Since both were surely acquainted with Columbus’ navigations, it would not be surprising before the speculations by certain researchers, whether Münzer might not have been sent to the Iberian Peninsula as a secret ambassador to gather information about the results of those first travels by Columbus and the projects that the Spanish monarchy kept in such secrecy. In such a case, there is no doubt that he would have had power to deal with the Portuguese on maritime agreements. We should not forget that the mentioned letter, promoted by Maximilian and written by Münzer, was addressed to King John II. The Portuguese monarch, apart from demonstrating a great erudition, showed a great interest in promoting discoveries. But leaving aside all this, whatever the real reasons were that motivated Münzer to undertake the journey, what is certain is that the doctor born in Feldkirch has left us a rich material legacy which enables us to draw today all sorts of scenes and details of the Iberian Peninsula during the final stages of the 15th century.

Farinelli already said it: Münzer’s account was for him the most valuable description of travels around Spain in medieval times.

After leaving Nuremberg and after going through Germany, Switzerland, and France, on September the 17th, and having travelled seven leagues from Narbonne, the four friends reached Perpignan. It is from now on that Münzer’s account is credible in many of its aspects.

The Münzer’s account shows credibility when talking about circumstances, places and people that are known to us; it charges interest for the peninsular people interested in having information on the most varied questions, from the ones related to the customs of the Spanish population, to those registering the country agricultural production.

“The siesta”. Memory of Spain Series by Gustave Doré

Münzer also relates the traditional processes of the guilds that he becomes involved with; he reports the tastes of the working class as well as the refinements that preside over the lives of the powerful.

In the same way, he registers the humble buildings and the lavish ones upon which he gazes, the monumental constructions he finds, the decorative motifs that astonish him, the treasures safeguarded by the places he visits, and a long list of peculiarities that would be long-winded to reproduce here. He offers his particular view of all that by reproducing picturesque scenes that sometimes he portrays in an exaggerated manner. We must be very much aware of this last point, for it is quite likely that he made mistakes when dealing with certain events.

Münzer’s stay in Spain lasted five months, from 17 September 1494 till 9 February 1495. Since he arrived in Perpignan until he reached the Kingdom of Granada, he went around many points of the peninsular geography, among them, Figueres, Girona, Barcelona, Poblet, Cherta, Tortosa, Villarreal, Valencia, Alcira, Játiva, Alicante, Elche, Orihuela, Murcia, Alhama and Lorca. On 16 October 1494 he set foot in the Kingdom of Granada in the town of Vera. To this city followed Sorbas, Tabernas, Almería, Fiñana, Guadix and La Peza. From 22 to 26 October he remained in Granada, a city he left on the 27 to go to Alhama.

From there he travelled through Vélez-Málaga, Osuna, Marchena, Mairena, Seville, Niebla and Sanlúcar. On 12th of November, leaving behind the frontiers of the Kingdom of Castile and getting into the territories of the Kingdom of Portugal, he reached Serpa.

Sanlúcar de Barrameda (1567). Anton Wyngaerde.

Unfortunately, despite the formation that Münzer supposedly had, a doctor’s degree in medicine and a vast amount of knowledge he acquired in his many journeys, his accounts sometimes lack accuracy. Maybe his wide culture could have allowed him to expand more upon some events on which he assured he had firsthand information. And no doubt he had many talents, appropriate enough to go more into depth regarding facts and situations he could personally check. All in all, despite the importance of his chronicle, which we cannot deny, we must take a precautionary approach regarding certain information.

One of the main difficulties Münzer had in compiling information was his ignorance of Spanish language, so he could only deal with clergymen with whom he communicated in Latin.

Regarding this latter point, we should not forget, for instance, that Münzer knew little of our history; besides, he did not know our language, so Latin was the only oral medium he had to address to the Hispanic population more directly. Such limitations reduced the scope of his interlocutors, mainly composed of clergymen. Consequently, all these factors should have been taken much into account when considering some of his assertions. They were often called into question as long as they came from someone with scarce critical resources to describe accurately what he saw and heard in our country.

There is much to say about Münzer, for just by reading a little about any episode, his disproportionate patriotism catches our attention, for this feeling leads him to identify with his Germanic origins in multiple passages. Such a disproportionate fervour makes him fall into continuous allusions to places from the country he comes from, settings that are compared, at the same time, when he recreates the new place that he visits. This is moreover reinforced by the fact of referring repeatedly to the contacts he confesses he had with people from his own land who had settled in the Iberian Peninsula. For instance, he tells us about his encounters with German traders who live in the regions he passed by, a circumstance which, apart from satisfying him enormously, provides him warm hospitality, allowing him to communicate easily.