The vanished Arab monuments of Granada

The capital of the Nasrid kingdom was extraordinarily populated for its time, with a considerable architectonic density. At the beginning of the 19th century, there were still many remains that survived from the legendary times of Al-Andalus, and Granada was the city in Spain with the most monuments from its Islamic past.

Upon the gradual expulsion of their inhabitants and the installation of new settlers, parish churches and convents, along the lines of the Ancient Regime, resulted in important transformations that turned the place into a city dominated by domes and bell towers of churches.

Obviously, the more we know about a building, according to its descriptions and images, the more we mourn its loss, and it remains in our minds that those lost in the Ancient Regimes are like a nebulous abstraction that leaves us indifferent, while the most documented destructions from the last two centuries hurt us like cruel mutilations. Yet, it would not be fair to say that in these centuries more has been destroyed than in the previous ones; suffice to say that between 1492 and 1571 the greater part of the mosques disappeared. What is true is that demolitions that have taken place in contemporary times are more unforgivable. For, even if maurofobia (fear of Moors) does not exist as it did in the past and given the increasing importance that everything related to Al-Andalus has gained since the Romantic movement, municipal authorities and Granada’s citizens may well have been more conservationist rather than being so involved in imitating the urban fashions and the architectures that were being developed in the big European cities. In any case, the interest in the legacy of Al-Andalus allowed people who were sensitized to heritage to leave us descriptions, drawings, and pictures of these painful losses. That is why I will mostly talk in this text about the demolished buildings from the liberal revolution until today and make only a precise reference to any outstanding monument from the many that we know have disappeared before, from which we hardly save more than its name. I will leave the Alhambra and its environment aside, as it might deserve its own article.

Talking about the Muslim buildings that have disappeared in Granada is in principle a subject of wide chronological scope that would lead us to its medieval city for, after all, the legendary palace of king Badis, (located at the Qasabat Qadima in the Albaicín), and known as the “Rooster House,” named for the weathercock that crowned it, might have disappeared already before the Catholic Monarchs arrived to the city, given the existing tradition among the Arab monarchs of demolishing the palaces of preceding dynasties. Today, not even its archaeological remains have been found, which poses an archaeological puzzle.

The best-documented of the buildings that have been demolished in order to open the Gran Vía (1895) was the palace Cetti Meriem —or Casa de los Infantes—, whose owner was a family related to the Nasrid dynasty.

Among the most regrettable destructions we can mention is the Casa de las Monjas (House of the Noons), built by no less than the king Muley Hassan. The building was already quite renovated when the Baroque painter Fernando Juan de Sevilla inhabited it, but it kept a beautiful courtyard which Mariano Fortuny and other artists painted before it was demolished in 1877.

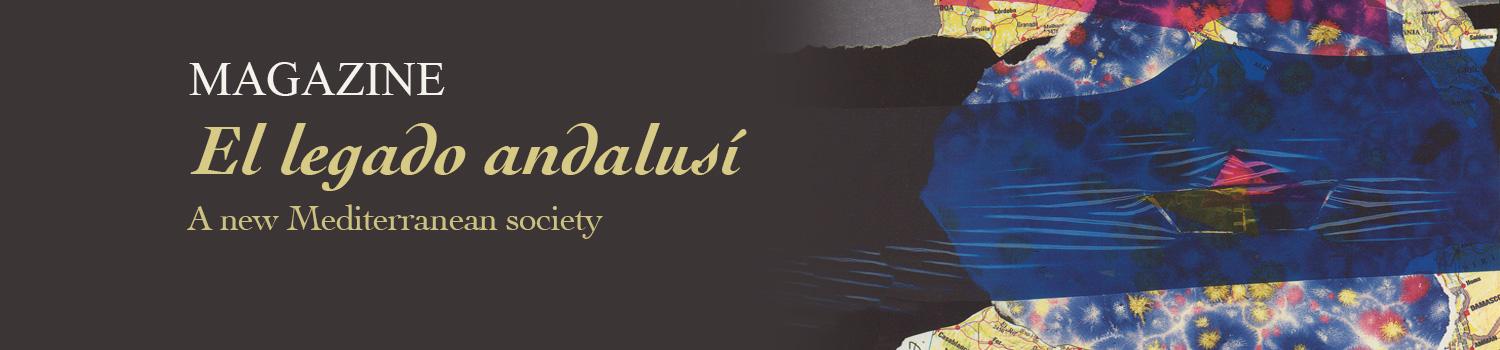

When the quaint river Darro was transformed into a street open to traffic, a part of the city, with its little bridges and hanging houses, the so-called Riberilla that had mesmerized some Romantic travellers, disappeared.

This image shows it with the vanished bridge of the Baño de la Corona at the back, and that of San Francisco in the forefront, towards 1870.

The palace of Cetti Meriem had a courtyard with elegant porticoes on pillars and its spacious rooms were very well preserved before being demolished. The Monuments Commission studied it in detail, saved some elements and drew some replicas of the plasterworks because its intention was to rebuild it in another place, a project that was ultimately abandoned due to the lack of funds.

Other houses with Nasrid elements perished also because of the construction of the Gran Vía and, unfortunately, they were not as well documented as the former one. There were remarkable remains in some buildings that were altered previously, like the Ecclesiastic School (Colegio Eclesiástico) or Casa de la Posadilla, or in the streets that tourists would seek in vain on a map (Azacayas, Pozo de Santiago, Lecheros, etc). In the opinion of those who promoted the opening of this avenue, those buildings were old and unhealthy, a quite trite argument that is still used when a historic building or quarter is intended to be demolished. However, the demolition of the downtown area’s ancient Muslim madina, aside from the irreparable losses of patrimony, also aggravated the chronic problem of housing for the working classes —who were driven to peripheral neighbourhoods, like the Albaicín.

In this quarter many Nasrid and Morisco houses have been lost over the last two centuries. These buildings were turned into tenement houses and weaving workshops, the occupation of their poor dwellers. The low rent that owners got from the leases did not encourage them to undertake maintenance works, so the buildings gradually deteriorated until the inhabitants were dislodged and the buildings demolished.

The house at number 12 Benalúa Street was also a remarkable palace, whose elegant marble columns informed us that the building originally housed an octagonal pavilion; had it been preserved, it could have been one of the most significant works of Nasrid architecture; yet it was already dismantled when historian Manuel Gómez-Moreno Martínez was born in the building. Later, it suffered successive transformations which distorted it, until being demolished in 1975 to build the Residence San Rafael.

Many other houses in the Albaicín had Andalusian elements that were lost after their demolition. Of a few we know their name and location (Casa de la Columna, house 22, Placeta de Fátima; house 1, Bravo street; house 12, San Luis street…), but of others we have only very confusing notes such as that written by an editor of the Granada newspaper El Granadino published in 1848 telling us that “a beautiful monument of Arabic architecture, which can be seen in every collection of Granada’s views, from Spain and abroad” was dismantled to reuse its materials, and also, how another remarkable house near the church of El Salvador was demolished, and that a fan of antiques purchased “three dainty arches which adorned the doors of the yard gazebo”.

It is even more outrageous that already in 1945, the town hall authorised the demolition of the house at 3, Plaza de Villamena, to build a bombastic building of neo-imperial airs. It was about a remarkable palace from the 16th century, which had later suffered important subsequent reforms, although it still preserved a cistern and the beautiful embellishments of the courtyard porticoes. No less pitiful was the destruction of the big pool which complemented the Alcázar Genil, where the Nasrid kings enjoyed simulating naval battles. A part of this big pool was swept away because of the works done in the Camino de Ronda, and of that which remained, it was destroyed recently by the construction of blocks of flats. Recently, during the constructions works of underground in Granada, an important part of this pool, of large dimensions, has been excavated, and it is on display at the Alcázar del Genil station, where it can be visited.

Urban reforms, particularly the broadening and the opening of new streets, were what left the deepest footprints in the architectonic legacy and in the medieval urban layout during the 19th century. The destruction of houses and bridges, to give birth to an anodyne street, was the most regretful loss that Granada has suffered from the perspective of the urban picturesque.

The river was vaulted in stages from Plaza Nueva toward the Genil River. The bridge of Baño de la Corona, the most important in the river Darro, had been enlarged by the Christians to give shape to the square, and on the old arch of the bridge they erected a five-story building which helped to reduce the cold air flows which make the winter harsh in this part of the city. Further down, there are the humble bridges of San Francisco and del Carbón, whose keystones and artless parapets were similar to the ones that we can see today in the Carrera del Darro. Next to the current post office building was the bridge named del Álamo (the Poplar) or de los Curtidores (the Tanners). In Muslim times, it probably was part of the wall and had a grating to prevent walking on the riverbeds. In 1875 the bridge of Santa Ana, also called the Cadí, perished, this time to enable the enlargement of Plaza Nueva at the expense of reducing the Carrera del Darro. All the disappeared bridges were single-span, and they showed the story of the river in their architecture by means of stratified marks. The demolition of the walls was one the characteristic measures of the nineteenth century urbanism. Given that the ancient fortifications had lost their military function, by demolishing them new streets could be built that also embellished the city according to the criteria of the time.

In Granada, it was the willingness of improving traffic, the organization of housing layout or speculation which were the reasons that led to the destruction of numerous gates and some stretches of the walls that the city had outgrown in preceding centuries.

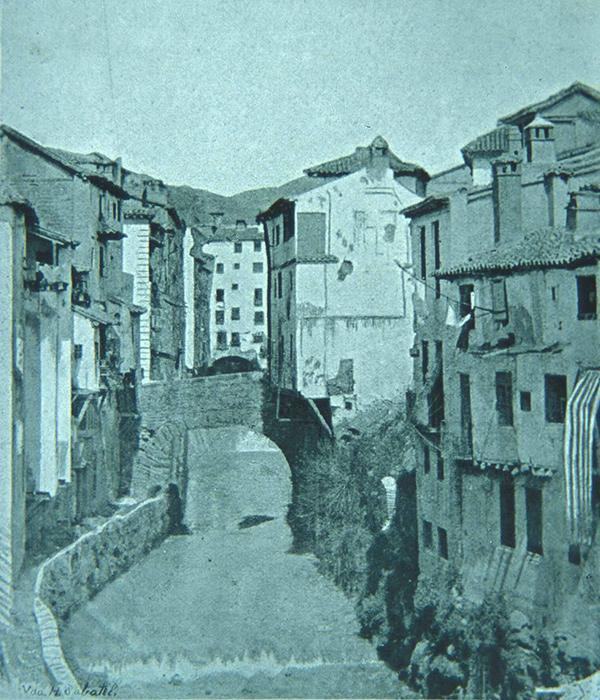

Alhacaba Gate near of Elvira Street. (Meldhal, 1860).

The Puerta de Elvira (Elvira’s Gate), which today has been reduced to a large arch, was actually a small fortress where several gates directed people in different directions. As it was a very busy place, around the 19th century, those gates were demolished, among them the so-called Alhacaba, whose pointed horseshoe arch was from the Zirid era.

In these same times, the Puerta del Sol (Sun Gate) was also built, which opened inside a solid tower and named this because its arches pointed towards sunrise and sunset. The gate was part of the wall which was descended from the Bermejas Towers that separated the neighborhoods of Mauror and Realelo, and was devastated in 1867 simply to regularize this place that was hardly frequented.

The Nasrid castle of Bibataubín suffered a profound remodeling in the 18th century to become a headquarters. The moat and some towers were eliminated, and all the rest was outgrown, including the big octagonal tower that is still preserved. A high tower rose next to Plaza de Mariana Pineda which was unfortunately demolished in 1967 to build a block of flats. Annexed to the castle there was a gate in the city wall in which the Christians had installed a chapel dedicated to Nuestra Señora de los Remedios. Its destruction was planned by the municipality to take place on the eve of the War of Independence, although finally it was the French who tore it down. Napoleonic troops also dismantled it and afterward dynamited the Olive Tower. At the end of the war, a small oratory in neoclassical style, the hermitage of San Miguel Alto, was raised there, which diluted the military character of that part of the city.

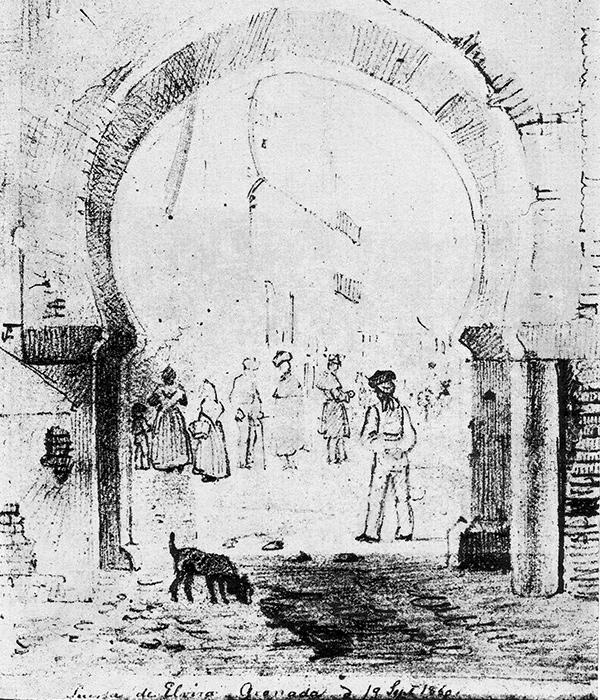

Depiction of the Gate de las Orejas on its original site made by David Roberts around 1834.

Remains of the same gate that could be saved, which are now in the woods of the Alhambra.

Next to the Plaza Bibarrambla was the door of the Ears, so named in Christian times for the perverse tradition of hanging there the amputated limbs of criminals. The gate consisted of a big square tower where a formidable, pointed arch with stone voussoirs opened to another, smaller horseshoe arch and a bended shape passage. Christians added a chapel, and it was so as the Romantic artists drew it, for in it they saw one of the most beautiful corners of the city. The city mayors and architects of the second half of the 19th century did not share the same opinion; it became a bother for them in an area under regulatory plans, and besides, there was a prominent individual interested in its demolition to revalue his property.

After several frustrated attempts to demolish it, including the one in 1873 that President of the Spanish Republic Pi i Margall managed to stop, and despite having been declared national monument, the gate was demolished by surprise in 1884. The mayor celebrated his achievement by firing rockets, while the Monuments Commission, feeling outraged, offered their resignation. When the demolition was taking place, some remnants of the stoneworks were kept, and they were used by Torres Balbás to reconstruct a part of the gate located in the woods of the Alhambra, where it still remains camouflaged by vegetation.

Similar to this was that of the Fish, built in the 18th century and whose name was given by the Christians because this was the place where fish from the fish from coast of Granada were unloaded. According to the playwright and liberal politician Martínez de la Rosa, it also had a vaulted passage with three arches. The gate, together with the terraced platform that was added, and a part of the wall which connected it with the Cuarto Real de Santo Domingo, was demolished during the middle of the 19th century. In the same way as the former one, the Millers’ Gate was part of the wall which protected the potter’s suburb, the current Realejo, and it was located at the end of the homonymic slope. Demolished in 1833, we know nothing about the physical properties of the gate through which the Catholic Monarchs entered Granada to the dismay of the Muslim population.

Some convents, such as the Jesuitical Colegio de San Pablo and the Santa Cruz la Real, marked out their properties by long stretches of walls and towers. The exclaustration of these monasteries meant their disappearance, in the first case to create the botanic garden, and in the second to open a street. Also in the Albaicín, the secularization of the convents of Agustinos Descalzos and Mínimos de la Victoria involved the destruction of the walls which passed by their orchards, being transformed into the gardens of the carmenes (typical houses of the Albaicín).

Regarding to mosques, we could talk about the dozens of them that were demolished to build churches in the process of the deployment of Catholicism in the new Jerusalem as, so say the rhetorical chroniclers of the Ancient Regime, was the city of the river Darro. It would be hard to point out how many of those mosques had any great size or ornamental richness to stand out over the usual simple décor of the oratories from Al-Andalus. We would think immediately of the great mosque of the Albaicín, which the traveler Abd al-Bassit classed as “wonderful,” which Hieronimus Münzer, who visited Granada shortly after the conquest of the city, described as “an extremely beautiful mosque, with eighty-six isolated columns”. Today, we only have an entertaining yard with lemon trees.

Despite being older and rustic, but of inestimable value, was the aljama mosque (main mosque) of Granada, a Zirid building whose prayer hall was constituted by a forest of columns, each of them opening to four arches that held up small vaults. It had three Access doors, plus another one which connected with the home of the faqīh (expert in Islamic jurisprudence), and in its yard there was a big water fountain for ablutions.

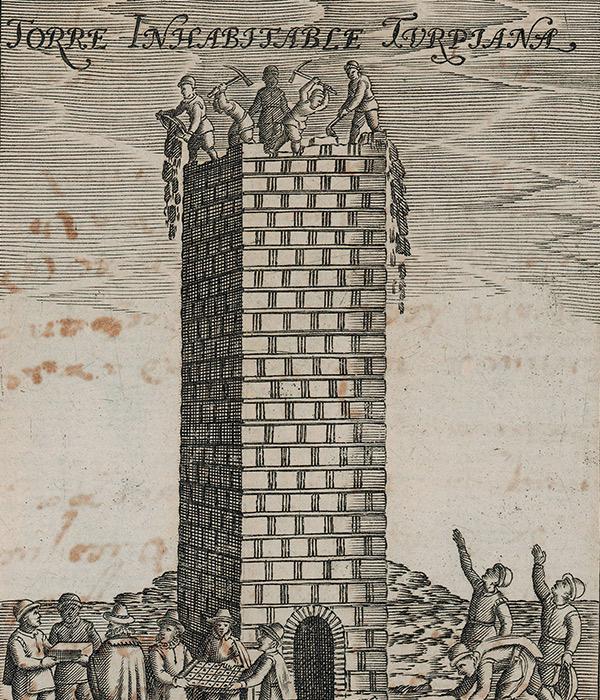

Francisco Heylan, «Detail of the inhabitable Turpiana Tower”, (ca. 1610) 1610. Archives of the Sacromonte Abbey of Granada.

The mosque lost its minaret at the end of the 16th century, known since as Torre Turpiana, at whose base have appeared the first findings of that opera soap as the fraud of the Libros Plúmbeos (Lead Books) of the Sacromonte. The prayer hall, however, was kept as the sagrario (tarbernacle) church, with the perimeter naves converted into chapels, as can be seen in the mosque of Córdoba. Unfortunately, the ecclesiastical council decided to demolish it in the beginning of the 18th century to build a Baroque church, according to Hurtado Izquierdo’s Project, which later on was modified by José de Bada. Although the new building was an example of notable architecture, there is no doubt that the aljama mosque, under whose arch had passed the generations of seven centuries, was a building unique in its architecture.

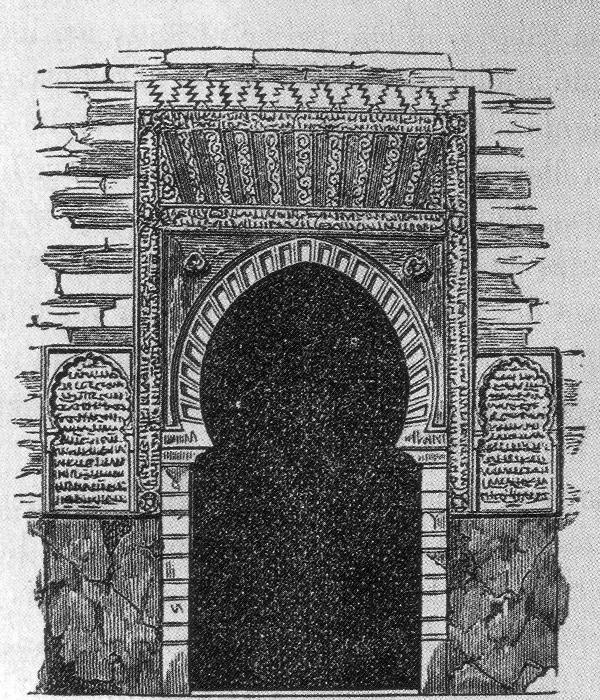

Hypothetical design of the façade of the Granadan Maristan (presently Madraza palace).

By the aljama mosque there was the Madraza, the Koranic university converted by the Castillians into the headquarters of the city hall. The necessary work to adapt the building to its new function were undertaken started earlier, but it was in 1722 when the extent of the changes left the Muslim architecture destroyed or concealed. The building could only be accessed through a door with inscriptions from which only some remains can be seen in the Archaeological Museum. Classrooms, rooms and the oratory, which can be visited very much restored, were accessed through a courtyard.

A very simple type of construction, at the same time religious and funerary, of a kind we can find hundreds examples in Morocco, but which has been almost totally erased in the lands of Al-Andalus, was the marabout. These building built in high spots to perpetuate the memory of some Muslim of exemplary life, consisted in a single square room roofed by a dome. From the many marabouts that should have been in Granada, only two have been preserved, thanks to their use as hermitages. One of them is that of San Sebastian, which still exists, and the other is the San Anton el Viejo, located in a promontory near the Puente Verde, which seems to have been decorated with tiling. San Anton’s friars took care of the hermitage, but when the Ecclesiastical Confiscation took place, the building was sold to an individual who demolished it. At that moment, the popular pilgrimage during which the hermitage was visited every 17th of January, had already disappeared.

Baths were an essential part in the urban layout, and they were very numerous in the big cities of Al-Andalus. However, many historians have pointed out that the epidemics of plague during the 14th century provoked in Christian Europe a great distrust of water, as they considered it to penetrate the skin and carry disease. If we add to this the religious jealousy towards a habit they considered hedonistic —during Roman times many were the stoics and Christians presumed not to frequent the baths—, we can understand that hygiene was reduced only to the bare essentials among the Christians who conquered the Kingdom of Granada.

Baths were closed in the first periods of Christian rule, but were not destroyed, because they were strong constructions with solid walls and vaults which were useful to store foodstuffs, washing, and to be subdivided into different dwellings or even transformed the cellars of the new buildings which were erected over them. This is the reason why there are many baths that have survived until contemporary times even though urban reforms and the faster process of architectonic renewal have unfortunately meant the disappearance of many of them.

There are still remains of the sumptuous bath that was popularly known as Casa de las Tumbas (House of the Graves) near Elvira Street. At the beginning of the 20th century, the building conservation was complete, although it was divided among several owners that demolished it gradually. We can regret, above all, the loss of its wide temperate room, whose nine-pointed arches were supported by columns of diverse epochs.

We can tell a very similar story related to the bath located in the Albaicín’s Agua Street, the biggest the city ever had, and whose ruins, very fragmentated are spread today among four houses. Much worse luck befell the bath in the Arrabal de los Alfareros (Potter’s Quarter), whose last room was destroyed in 1967. It was a bath of huge dimensions from which some archaeological remains have been excavated lately. Much earlier, during the works undertaken to build the Gran Vía, the Baño de la Zapatería (Shoestore Baths) perished, even though it was well preserved and was distributed in several homes, it was hastily demolished before being properly studied.

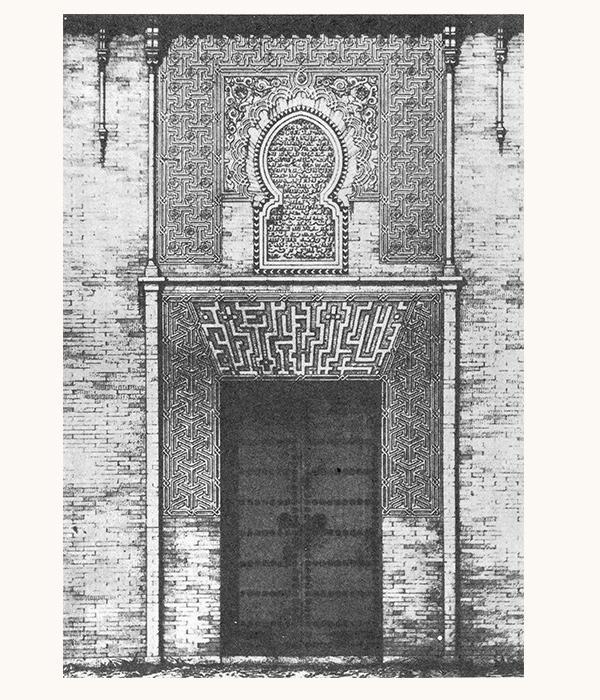

One of the buildings whose loss it the most painful in the Maristán, a hospital for the poor, built at the peak of Nasrid art. The building had a very beautiful façade whose reproduction to scale can be seen in the National Archaeological Museum, and a big rectangular yard from which a gallery is kept, as well as one half of the others. In the pond in the centre of the yard, there were two lions pouring water, which can be seen in the Alhambra Museum. The building had been a mint, a tenement, a military headquarters, and a jail. However, neither its historical nor its artistic value prevented its owner from demolishing during the middle of the 19th century. The most important remains that we keep as well as the detailed graphic documentation elaborated prior to its demolition justify its reconstruction.

. In order to accommodate the traders and peasants who went to the souk with their merchandise, alhóndigas, a sort of hostel named funduq in Morocco, were built. We only have kept one in Granada (as there were several) known as Corral del Carbón, headquarters of the Foundation El legado andalusí. According to architect Carlos Sanchez’s assumptions, it is probable that another one was in Plaza Nueva, the building that the Catholic monarchs turned into a hospital named de la Encarnación. A view of an imposing wooden balcony covering its façade stands out can be seen in engravings from the 18th century, and we also know that in its interior there were good frames as well as an austere patio. Unfortunately, it was demolished in 1944 to enlarge the square. The Alhóndiga Zaida was an old Nasrid building adapted to be a market, that was used by the settlers. Although in the 19th century it was found already transformed and diminished, it conserved very interesting Muslim remains until an accidental fire in 1856 destroyed it, which brought about the construction of the building El Suizo. We can see in the Alhambra Museum a beautiful capital from the 14th century which was lifted out of the ruins.

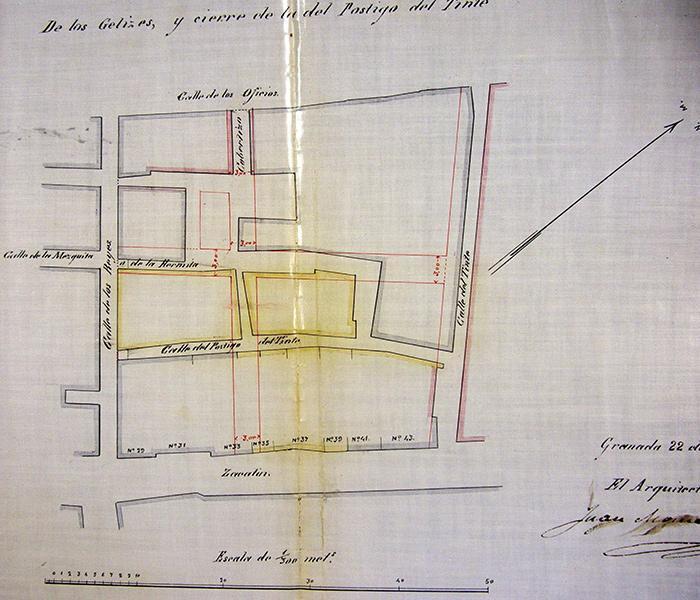

Plan of the setting of a sector in the Alcaicería (Juan Monserrat y Vergés, 1884).

Another fire destroyed the west part of the Alcaicería in 1843, while the east part was a victim, decades later, of the realignment of streets, which entailed the destruction of all the buildings, including the Silk Customs, which had an arch decorated with plaster and some interesting ceilings.

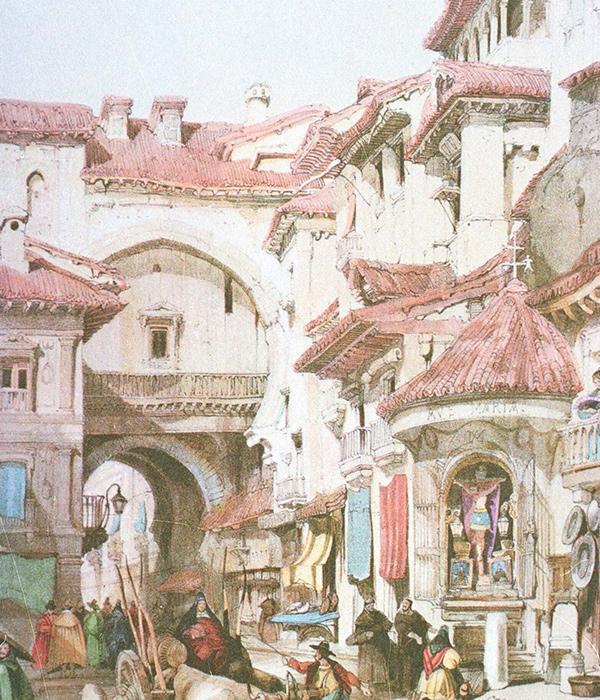

The Alcaicería was a section of the souk closed by doors to protect the valuable goods. Its narrow streets hosted two hundred small shops closed by wooden gates which could be disassembled and even used as eaves. In its intricate network there were very picturesque corners, and even a mosque that was rebuilt as a hermitage, a sacred action that Christians completed by placing niches over the entrance arches to access the place. The reconstruction of the Alcaicería from 1844 was mainly directed by architect José Contreras, popular for having started at the Alhambra a dynasty of restorationists who substituted the original ornaments with faithful copies. This skill of copying the plasterworks was used in the Alcaicería, rebuilt as a neo-Arab shopping arcade, whose shops were inspired by the structure of the tabernaeof the ancient Roman world. The new Alcaicería was very different from the Muslim one, but today we see it as a pioneer example of orientalist architecture that was to be so much in vogue in the coming decades.

Epílogo

When a building is demolished, a piece of the story of a city and the people who inhabited it is lost. If that building is part of a city that was the capital of the Zirid Taifa Kingdom, of the Almoravid and Almohad Al-Andalus, and of the Nasrid Kingdom, then we are talking about the loss of an important chapter of the Spanish medieval history. The tragedy of the destruction of historic heritage is almost always due to narrow reasons like an individual’s speculation or the mimetic matching to a passing fashion. With regard to the many voices that have been raised, and that are still being raised in Spain to denounce the urban problems of historic cities or to justify that destruction is the price we inevitably must pay for progress, suffice to point out that the challenge that preservation has always presented in Granada is nothing but a bagatelle beside the ones that Venice has had to face, and however, the conservation of the Italian city is much better, and nobody will dispute that it has been for good.

Since the times when Romanticism became the frame of reference for Granada, the three main elements of its amazing layout have suffered a variety of fates. The need of preserving the Alhambra has led to a broad consensus, and its state of conservation is excellent. The wild and contrasting landscape that surrounded the city underwent a more dire fate, for it has been the victim of severe ravages. Referring to the picturesque city, we have undertaken an overview of the losses that the medieval heritage has suffered and is arguably neither small nor secondary.

The Romantic travellers knew buildings in a seemingly irreversible deterioration, like the Corral del Carbón and El Bañuelo, which are now restored and open to the public, a fact that we are proud of. Yet it is a shame, however, that we cannot cross the bridges of the Riberilla, sit in a gazebo at the Cetti Meriem palace, or see ourselves reflected on the pond of the Maristán.

Juan Manuel Barrios Rozúa

Professor at the High Technical School of Architecture of Granada,

and author of the book Guía de la Granada desaparecida (Comares Publishing house, 1999).