Arab-Norman Palermo, a reflection of al-Andalus

By Ana María Carreño Leyva

Fundación El legado andalusí

Islamic culture left a vast legacy spread over different regions in the Mediterranean area, living with the local cultures and giving as a result new artistic forms.

The intensive human traffic that spread across the Mediterranean Sea since before the Middle Ages was mainly due to the development of maritime navigation. It was the easiest way to travel, and it established connections to the most important commercial and cultural places across the then-known world; shipping lanes were simply more feasible than those on land.

In the lands surrounding the old sea that the Romans called Mar Medi Terreneum (Sea among Lands) and that the Arabs called al-bar al-abyad al-mutawassi, The White Middle Sea) Arabic was the predominant language.

Following the example of al-Andalus on the other end of the Mediterranean, when Arabs reached the island of Sicily, they found the remains of former cultures which had been set out there since Antiquity.

It was the Phoenicians the first to set foot in the island. Greeks, Carthaginians, Romans, Vandals, and Byzantines followed. Sicily was quite a coveted place throughout all the ages.

It was in late 9th century when the first Arabs landed on the island. They belonged to the Aghlabid dynasty from Kairouan, in what is now Tunisia. The conquest lasted over one hundred years. As a result of Dar al-Islam’s expansionist policy, Arabs were progressively annexing further territories, together with the Arabization of the population and their toponyms. Hence, once they took over the port of Palermo (named Panormo by Greeks), it was Arabized as Balarm. The Aglabid conquerors put into practice methods that had proven largely succesful in other places: a genuine integration into society of different cultures, the freedom of worship and, above all, the implementation of diverse advances in agriculture, science, architecture and practically every aspect of daily life. And due to its central position in the Mediterranean, Sicily spread a great influence as an example of cultural lustre and economic growth all around.

Of greatest importance was the management of agriculture, the primary engine of economic development. In Roman times, the island was already famous for its excellent cereal crops. With the Arabs, the large properties were divided into smaller ones managed by farmers who successfully introduced the cultivation of new products like cotton, papyrus, pistachio, rice and dates. But it was the cultivation of citrus fruits that gained the upper hand. It was by far the agricultural outputs that generated the most revenue, as well as prestige for their exceptional quality. In Palermo, the Conça d’Oro (Golden Basin) is so called precisely due to the colour that the vast expanse of orange and lemon groves added to the landscape in the past.

As a result of the two centuries that the Arabs remained in Sicily, and thanks to the implementation of many innovations in diverse areas, an unprecedented economic and cultural flourishing took place on the island.

Architecture, inserted into well-taken care urban solutions and surrounded by lush, manicured gardens, represents the most obvious example of this cultural booming. As they did in al-Andalus, the Arabs reused the materials they found belonging to the constructions of previous settlements, mainly Roman. However, they masterfully applied their own techniques and improved the extant hydraulic systems like cisterns and aqueducts. They implemented technical solutions such as building subterranean water channels to avoid water evaporation caused by high summer temperatures. Spectacular gardens never seen before in Europe adorned the urban and palatial spaces, such as those existing in al-Andalus, of oriental inspiration, with water as the focal point.

The political dynamics that rocked the Mediterranean in those times, made it so lands passed from hand to hand in few centuries. By the end of the 10th century, the ascent to power of the Fatimid dynasty −the rulers of almost the entire Islamic world, formerly in the hands of the Abbasids−, led to the weakening of the Aghlabids in Sicily, once they were defeated in the North of Africa.

Former dwellers of the island, the Greeks, returned then to the island, this time allied with new conquerors, the Normans, of Viking origin (Norman means “men from the North”), who after establishing a duchy in Normandy (France) in the 9thcentury, conquered England, and came to become more powerful than France. After having invaded almost the entire south of Italy, they conquered Sicily in 1061, and in 1072 they declared Palermo its Christian capital. Half a century later, the son of Roger I, the conqueror of Sicily, Roger II was crowned as king of Sicily.

Upon the Norman arrival to Sicily, they found the vast and fabulous legacy left by the Arabs. Then they knew how to make the most of it to create their own contributions. Roger II’s kingdom was one of the three largest in the Europe of his time. At the beginning of the 12th century, the Norman kingdom was not only today’s Sicily, but also the mezzogiorno of Italy (the duchies of Apulia and Naples). By the middle of the same century, Norman frontiers expanded to Spoleto in the province of current Perugia. The coexistence of Normans, Byzantines, Greek, Arabs, Lombards and native Sicilians marked an era characterized by a prolific interculturality.

Roger II’s own personality shaped the cosmopolitan character in Sicilian society. Educated by Arab and Greek tutors, his palace halls bore witness to the most eclectic exchanges of those times. His court was a compendium of all the former legacies, to which the scholars from the Latin, Byzantine, Greek, and Islamic worlds added their respective contributions, furnishing Norman culture with its own personality with a unique artwork whose splendour has come down to our times.

If Arabs had taken advantage of the infrastructures left by Romans, the Normans did the same with the legacies they received from the Arabs. Roger II went further and improved and adapted them, commissioning the very same Arabs to the tasks for which they were originally responsible. Roger II knew also how to harvest the results of other activities whose way of management he implemented, as for instance, statecraft and public administration, which the Arabs masterfully handled. In fact, Arabic was the language of government, and Sicilian today has many words of Arab origin, as it happened in Spanish. Geographer from al-Andalus Ibn Jubair included Palermo in his itinerary when he returned from Mecca in 1183, and he left us an account enriched by the words of Roger II whom he interviewed several times. He describes Palermo as the metropolis of the Mediterranean islands, how daily life was for Muslims in the Christian kingdom, and he describes how were its cities, palaces and other structures. He provided testimony of how administration was handled and how they combined the benefits of wealth and splendour, “ having all that you could wish of beauty and all the needs for subsistence. It is an ancient and elegant city, magnificent and gracious, and seductive to look upon. It proudly sets between its open spaces and plains filled with gardens. It is a wonderful place, built in the style of Cordoba, entirely from cut stone known as kadhan (limestone), with broad streets and roads, it dazzled the eyes with its perfection. The women of this city still follow the fashion of Muslim women, and they are also veiled.” ”.

Another illustrious Andalusi who knew Roger II’s court first-hand was the geographer al-Idrisi, who undertook the giant geographic work assigned by the Norman king in 1154. Known as Tabula Rogeriana, the king christened the ensemble of works Nuzhat al-Mushtak, recognised in history as the Book of Roger.

Twentieth-century historian Julius Norwich, author of several distinguished works on Sicily, wrote that Norman Sicily “stood forth in Europe −and indeed in the whole bigoted medieval world− as an example of tolerance and enlightenment, a lesson in the respect that every man should feel for those whose blood and beliefs happen to differ from his own.”

The compendium of cultures, whose echoing legacies still resonate in Sicily, are clearly shown in examples like Arab-Norman architecture.

The church of Santa María dell’Ammiraglio, also known as la Martorana, which stands in the core of historic Palermo downtown, is a perfect representation of this cultural palimpsest in its architecture: Byzantine mosaics adorn Arab pointed arches and are crowned by ribbed vaults above, while geometric mosaics covering the floor show both Roman and Arab influences.

This beautiful construction is but one of the many “open books” of Palermo’ history, where we can learn how Normans understood Islamic art. Santa María dell’Ammiraglio was built by Syrian architect of Arab origin Giorgio of Antioch, who was also an admiral of Roger II, and this is why the church bears also his title. In a column in its interior there is a column with a Qur’anic inscription in Kufic Arabic script. (There is another inscription like this in the Monreale cathedral, outside Palermo).

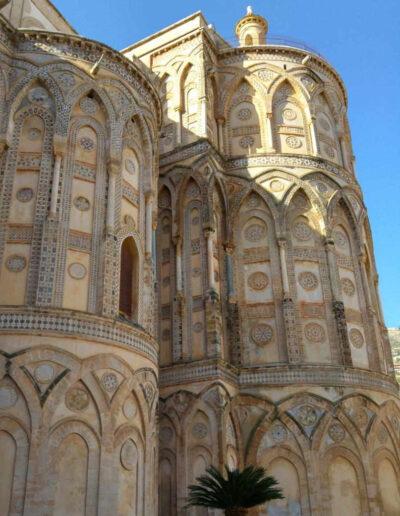

Another outstanding example is the Palatine Chapel.. It was built by Roger II on the site of a former chapel, from which just the current crypt has been kept. It has a basilica dome and three apses, according to the canons of Byzantine architecture. Yet its lush decoration, crowned by a gloriously elaborate wooden muqarnas ceiling, boasts the most genuine Islamic style, something almost unbelievable in a Christian church.

When Roger II died in Palermo in 1154, he was succeeded by William I, followed by William II, whom history later would nickname ‘The Good’ to distinguish him from his brother William I.

William II was the King of Sicily and Naples from 1160 to 1189, and his rule was crucial to follow up the development of art in Sicily his father had begun, together with the consolidation and unification of the Norman conquests in the island and the South of Italy. In the same way, he managed to keep the places in North Africa, by establishing the Kingdom of Africa in Tripolitania and Tunisia in 1135, until 1160.

William II undertook great constructive projects, among them the Monreale cathedral on the outskirts of Palermo and the palace of Zisa (a name that means “splendid” in Arabic) which his predecessor had begun. This palace epitomizes the Arab influence in the palatial constructions. As in al-Andalus, open spaces included water to accomplish its noblest task: the embellishment of places and to establish a comforting dialogue between architecture and gardens, always bearing in mind its practical reason, such as providing relief in the summer’s torrid temperatures in the Mediterranean area.

The mastery used by the Normans to adapt the different forms of art, show how they understood Islamic art and make it their own, by balancing the different influences and cultures that enriched the Sicilian society. This phenomenon has given as a result an art that has lasted throughout to our time, to let us know the extraordinary effects of multiculturality.

By Ana M. Carreño Leyva

Fundación El legado andalusí

Apses of the Monreale cathedral. CC 4.0-BY NC ND. panormus.es

The three apses decorated in Fatimid style excels on the austere appearance of the cathedral of Monreale

Arab inscription in a column inside the church Santa María dell’Allmiraglio, also known as la Martorana.

Sala della Fontana. CC 4.0-BY NC ND. panormus.es

Baroque frescoes were added in the 17th century in the walls of the Hall of the Fountain.

Benedictine cloister in the cathedral of Monreale

Built in an annex to the cathedral, the Benedictine cloister of Monreale shows the talent displayed by the Arb-Norman culture. Columns, everyone decorated differently with golden mosaics, are supported by capitals highly crafted. The basin of the fountain is shaped as a palm tree truck, always evoking the garden.

zisa-da-ferla2

Vista de 360º de la Zisa con el nuevo jardín, tras las obras que comenzaron a ejecutarse en 1993 y terminaron en 2011. ©Universidad de Palermo para iHeritage Las residencias de verano eran algo frecuente en la corte normanda, un gusto heredado de los árabes, grandes conocedores de las técnicas jardineras que desarrollaron con maestría aprovechando la abundancia de agua.

iHeritage

This Project has been developed thanks to the European Union financial support through the iHERITAGE I ENI CBC Med.

This innovative approach is aimed to introduce advanced technological as solutions in the monuments declared World Heritage by UNESCO, selected in the Mediterranean area for their reinterpretation in today’s world and their dissemination in the 21st century.

The Foundation El legado andalusí is involved in this project, together with other Mediterranean countries like Italy, Lebanon, Portugal, Egypt, and Jordan, and its work has consisted in the virtual archaeological reconstruction of the Generalife.

The monuments and sites inscribed in the UNESCO registers included in this project have been also collected in a comprehensive database of the Mediterranean cultural patrimony, which has been possible thanks to the transnational cooperation.

The part of the project which deals with the Arabo-Norman Patrimony in Sicily, has been developed by the Architecture Department of the University of Palermo, curated by Professor Rossella Corrao.

The main aim is to improve the level of information and communication and extending the valorisation of the Norman patrimony in Palermo and abroad by using augmented and immersive virtual experiences, and the innovative ITC technologies (Information and Communication Technologies). This system maximizes the involvement of public, both researchers, students and public, being also useful for including people with disabilities, overcoming the limits derived from the architectural barriers, without compromising the aesthetical integrity with ramps or elevators.

Webs generated by the project:

Immersive virtual experiences: Arab-Norman Itinerary in Sicily, Byblos (Lebanon), Alhambra, Generalife and Albayzín (Spain), Pyramid Fields of Giza (Egypt), Petra (Jordan) and Mediterranean Diet.

iHeritage in Palermo

Among other structures from the era of the Norman Kingdom of Sicily, the palace of the Zisa, and the Cuba have been reconstructed by giving evidence of their original aspect and functions, mixing scientific information and reconstructive hypotheses, with effects digitally created. In the same way, the qanats, subterranean infrastructures for the conduction of water, has been it has been reconstructed in 3D

The palace of Cuba, as well as the Zisa, were vacation homes dedicated to entertainment, relax and hinting, built in 1180 by William II of Sicily. It was a place to escape the summer heat, so it was surrounded by water ponds and fountains together with many exuberant gardens.

3D-virtual recreations of the Cuba, University of Palermo for iHeritage.

QR to visualize the 3D-virtual recreation of the Cuba.