Ali Mandri,

from Granada to the White Dove. The emigration of a free man.

By Rodolfo Gil-Grimau Benumeya.

“Tetouan is the city on the edge of the winds, for it sits in a valley where gusts come and go while the sun and the clouds deliver hazy glare. And this valley, saturated with the scent of orange trees, is so enjoyable that is increasingly filed with new white suburbs, open and ventilated.”

“So they, Morocco and Andalusia, are like the obverse and reverse of the same medal that complement each other’s styles, and it is not possible to understand one side without also seeing the other. This is the sense in which the country of the Maghreb imposes its most visible character: that which evokes the centuries of our ancient South, where Cordoba and Seville, Granada and Murcia were also a parade of arches, white swirling fabrics and vibrant and enthusiastic speech.”

Panoramic view of Tetouan.

Abu-l-Hassan ‘Ali-Manzari al-Garnati came from a family from Bédmar or al-Manzar −“the landscape, the scenery”− in Jaen today. His family name was phonetically transformed into al-Mandari, then al-Mandri, and in the way it appears as a family name in the Granadan documents: al-Manzari or al-Manziri, as well as Mandari in the documents related to the Granadan Moriscos. The vernacular form of his name –‘Ali al-Mandri− is the one that has remained in memory, which is still indelible in Northern Morocco and in history.

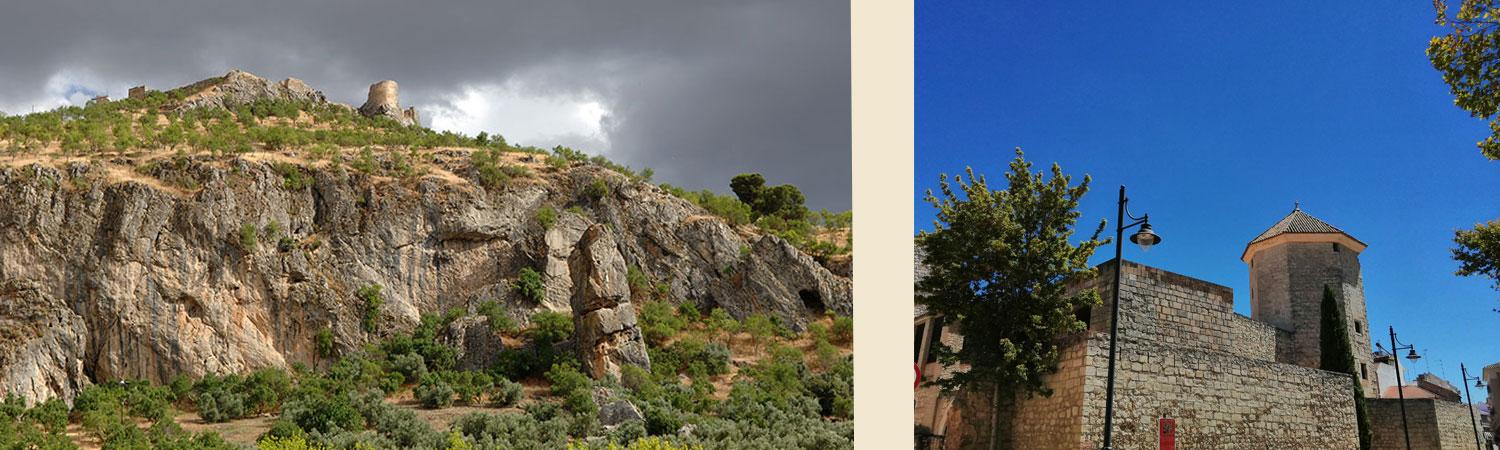

In the first part of the war of Granada against Ferdinand and Isabella and the parallel civil war, he was governor of Píñar, in the Montes Orientales Region (East Mountains) of Granada, and successor of King Abu ‘Abd Allah, namely Boabdil, against his uncle King al-Zagal. Harassed by Zagal’s troops and those of the Christians who occupied the fortresses of Cambil and Alhabar, and also by those following the orders of Boabdil, who the Christians kings had momentarily taken prisoner after the siege of Lucena −where he surrendered several locations− he abandoned or delivered the city of Piñar. Then, rather than reintegrating Granada, he decided to emigrate to the Maghreb, accompanied by many nobles and hundreds of warriors, with their families, willing to establish a bridgehead from where he could be able to keep on fighting and return one day.

Al-Mandri married Lahla Fatima, a princess from the Granadan royal family, who was nevertheless taken prisoner by the Count of Tendilla and detained for some time in the fortress of Alcalá la Real, from where she later travelled to the Maghreb, once his husband was established in the region north of Morocco. With Lahla Fatima, al-Mandri had several descendants who should have formed part of the first aristocracy in Tetouan.

Left, Castle of Píñar, Route of the Nasrids. Right, Castle of El Moral in Lucena (Cordoba), Route of the Caliphate.

Tetouan geographical position and its surrounding region made of it, together with its immediate proximity to the Strait of Gibraltar, a strategic and sensible point for the Mediterranean civilization probably since times of old. Proof of this are the name of its Mount Gorges, a variant of the name of the European Neolithic solar god, in the Amazigh Tittawin −Tetuán− “Las Alfaguaras” (Water Springs), the Phoenician-Punic settlement of Tamuda, and its river, partially navigable until the 19th century. Destroyed by the Portuguese in 1437, it had remained abandoned during ninety years within the territory under rule of Muley ‘Ali ibn Rashid, prince almost independent of Chaouen, the mountain town he founded himself and populated mainly with other Granadans and migrants from al-Andalus. In fact, ‘Ali ibn Rashid was married to Lahla Zuhra Fernández, a Mudejar or Morisca from Vejer de la Frontera, close to Cádiz.

Given the weakness of the Wattasids, who succeeded the Marinids and the Saadis who were to come later, both the defence of the frontiers and the attacks onto the Christian occupants came into the hands of these Muslim champions, the mujahidin, who were practically independent within their territories.

[1] Moroccan Berber dynasty that belonged to the same branch of the Marinids.

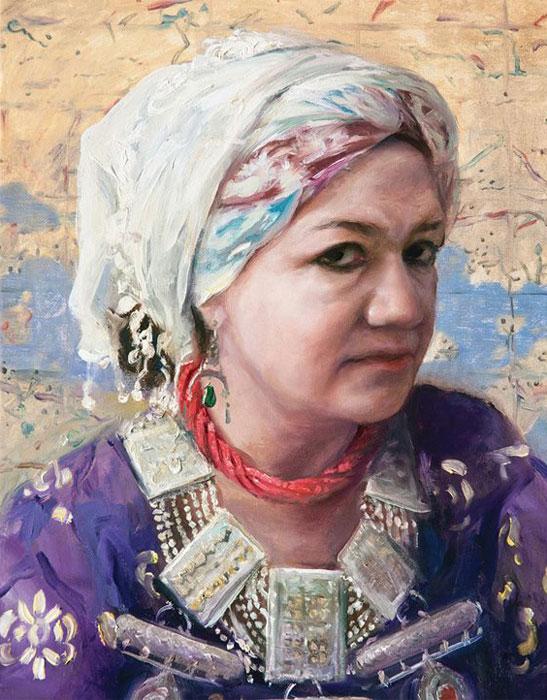

Muley ‘Ali ibn Rashid and al-Mandri probably had met in the very war of Granada, where many of these mujahidin had gone to fight. It is known that both chiefs kept, since the arrival of the Granadan, a strong friendship and alliance, which led to the marriage of al-Mandri with the daughter of Ibn Rashid and Lahla Zuhra, probably named ‘Aisha and known in history as Sayyida al-Horra, or more colloquially, Sitt al-Horra.

We do not know what had happened to Lahla Fatima; her mention disappears in the course of events. The marriage between Sitt al-Horra and al-Mandri might have taken place towards 1500, when she was some fifteen years old and he was around fifty. The age gap was not an obstacle to their mutual understanding and their ongoing collaboration until the death of al-Madari in 1540. She had learnt from him how to rule, a habit she already brought along from her father, Mouley Alí, and surely from her mother, Lahla Zuhra, the Morisca, both with strong personalities. The fortitude of her own character and the strength of that of al-Mandri connected well and, almost from the beginning of their marriage, she helped him in the management of the new city while he was out fighting, representing him entirely in the government later when he partially abandoned daily affairs.

They married their two daughters with the sons of other noble Granadan emigrants towards 1527, and approximately in those dates al-Mandri stopped entering into combat, afflicted by his injuries and a progressive blindness that left him without ease of movement. She was the ruler de facto, although legally and concerning authority, it was to be him until his death.

The free and autonomous city grew among volumes of white buildings plaiting its streets where its artisans worked extending their Andalusi knowledge. And the songs known as “Garnatí music” (music from Granada) sounded again, in memory of their origins, in the shores of the Genil and Guadalquivier Rivers, where this soberly refined music was born. Terraces were covered with flowers and plants curated by women who joyfully spoke from one to another wall.

But the Granadans did not know how to stand still; they plotted among themselves to get the power and the lineages in the same way they did in Granada. Al-Mandri and Lahla Fatima’s sons probably took part in this, together with other people like their son-in-law Hassan Hashim, native from Baza, and another of their sons-in-law, Abu ‘Ali. Immigrants from Granada, as much of from the rest of al-Andalus, and the Moriscos who arrived later, were actively involved in the corsair navigation a task officially permitted and boosted by the states, which generated wealth and limited the commercial, human and military capacity of their opponents, mainly the peninsular Christians. It was quite logical that in this “business” existed rivalries and disagreements intertwined with jealousy and politics, which was addressed both to Chaouen and Fez as much as Portugal and Spain.

The eagerness that al-Mandri, and above all his wife, showed to foster that activity, protecting and financing it, caused a stir around them, provoking feuds and mistrust both from abroad and Morocco. This started to be against them and the Sultan, who permitted it no matter the international agreements. But this seemed not to be important for them until 1539 and 1540.

Street life. Tetouan. ©Jesús Conde Ayala.

And in 1540 al-Mandri died. He was probably more than ninety years old, active in fact, never losing hope to be able to return, always negotiating even with the Austrias −“the old warlord still yearning for Spain” according to a contemporary witness. [2]. It is true that his difficult life and the age difference with Sayyida al-Hurra did not appear to have undermined their mutual support, since she was supporting him since the early years of their marriage and to the end took care of him and his work for freedom until his death.

[2] Gozalbes Busto, Guillermo. “Sitt al-Hurra, governor of Tetouan”. Proceedings of the International Congress the Strait of Gibraltar. Madrid 1987.

“Andalusi patio” in Tetouan by Jesús Conde Ayala

The truth is that Tetouan was an almost independent state, ruled by people from Granada and their heirs for a long time, and still retains the atmosphere and character of Granada within Morocco to which it fully belongs.