Valle del Zalabí. A primitive landscape

There are places whose landscape speaks volumes. In the north of the province of Granada, scarcely two kilometres from Guadix, the Valle del Zalabí (Valley of Zalabí) unfolds in a singular historic scene that fascinates the traveller.

The uniqueness of these lands was no doubt a decisive factor for different cultures to settle here since the Neolithic period. Valleys and river courses provided natural access for these primitive settlements, and the fertility of its irrigated lands, together with the newly developed uses of metals to build rudimentary tools to work the fields, all boosted the development of new agricultural techniques. This was the birth of the first urban centres in an enclave considered ideal for the richness of its resources, provided thanks to numerous favourable circumstances.

The favourable climate of the valley, which runs shielded by hills of clay, together with its superb location on the transit route to Almería, made of Exfiliana and Alcudia de Guadix the anteroom of the historically prominent city of Guadix. This city started to become important in times of the Roman Hispania, as it was crossed by the famous Via Augusta[1] , Julius Caesar founded the city in the year 45 B.C. under the name of Iulia Gemela Acci, giving it the political status of “Colony”. And scarcely two kilometres away is Exfiliana, or Esfiliana, so called due to its affiliation to the Roman centre of Iulia Gemella Acci (Ex- Julia, or on the outskirts of Julia).

[1] The Vía Augusta was the longest and busiest road built by the Romans in Hispania, with a distance of 1,500 kilometres. The road linked the Pyrenees with Cadiz.

The striking relief of the terrain is the result of an extreme and varied climate, which has caused extraordinary effects due to the erosion of rocky outcrops and clay hills. This has had a massive impact on the natural environment, creating a capricious morphology and intense contrasts of colours: the greenery of its fertile plains and pine forests alternates with the red ochre hillocks against the background of Sierra Nevada that adamantly switches the landscape from winter to summer.

Tracing the existence of this valley in the times of al-Andalus, we find numerous references, among them those from the great Algerian writer al-Maqqari (Tlemcen 1578 – Cairo 1632), who describes this cluster of populations as “a castle so big that it looks like a city.” The renowned geographer al-Idrisi also refers to it as Isn- Yiliana in a passage that describes the distances between Guadix and the village of Dólar, where he mentions that it is well-known for its pears.

According to professor J.A. Rodríguez Lozano, expert in Medieval History and History of Islam at the University of Granada, “the identification of Esfiliana has gone through diverse processes, and after recurring to phonetic, historical, documentary and geographic reasons, among others, in this work we try to stablish the most plausible identification of Esfiliana, is as a ‘towns to the south of Guadix (Granada)’. It is probable that it looked like a city, since it maybe had under its control Esfiliana, Alcudia de Guadix and, between them, the Salabín, mentioned by Mármol, and all of them together with Zigüeñí, from which depended administratively Esfiliana y Zalabín, which on its turn was dependent on Alcudia.”[2]

[2] Rodríguez Lozano, J. A. “Hisn Ŷliāna. Esfiliana”. Miscelánea de Estudios árabes e islámicos. N. 40. Universidad de Granada, 1991.

Shustar, home of Shustari

The prominent mystic poet Abu al-Hassan al-Shustari was born in the 11th century in Esfiliana, then known as Shustar. He was first educated in Xátiva (Valencia), and started to be interested in Sufism already in his youth. He was a mystic traveller, and after living in Morocco, where he became sheikh (master), he travelled to the Middle East and to Mecca in 1253. There he met his true master, Ibn Sabin al-Mursi, whom he succeeded, and overseeing also his disciples with whom he departed to Egypt. There he died in 1269, in the city of Damietta. Ruled by the Ayyubids ̶ the dynasty founded by Saladin ̶, the Knights of the Fifth Crusade sieged the city scarce fifty years before al-Shustari’s arrival.

Illustration that depicts the Attack to the port of Damietta, by C.C. Van Wieringen. ©WikiCommons

The category of these places, located at the edge of a significant route of communication, were upgraded particularly during the Umayyad caliphate. It was an obligatory route to reach the port of Almeria, one of the greatest in al-Andalus. It connected the western Mediterranean with the East ̶ an area which comprised almost the whole of the then known world ̶ , and its importance derived not only from the vast amount of business transactions that took place there, but also from the defensive and military possibilities that its fabulous strategic location offered.

In 1489 this area in northern Granada province became part of the Crown of Castile, following the surrender of King Muhammad XIII, known as al-Zagal, uncle of Boabdil, the last king of Granada.

During the Moriscos’ rebellion, which in Guadix had a great impact, Exfiliana played an important role, given its proximity to this city. It not only supported the revolt, but also gave refuge to those who were expelled from nearby areas such as Alcudia, Cigüeñí and the Zalabí, even though Hernando al-Havaqui was from Alcudia. Known as the “Great Constable”, he actively participated in the Moriscos’ rebellion against Phillipe II, while he (Hernando) was captain of the area comprising Guadix, Baza and the Marquesado (Marquisate) del Zenete when they revolted in the Alpujarras.

Accounts about the Moriscos in official documents of those times that are preserved, such as the titled Apeos que se hicieron por el Doctor Miguel de Salazar, en el año 1571, de todas las Haciendas de los lugares de Exfiliana, Zalabí y Cigüeñí que fueron moriscos (Demarcation made by Doctor Miguel de Salaza, in the year 1571, of the properties of Exfiliana, Zalabí and Cigüeñí that belonged to Moriscos), In 1571, after they were expelled from the Kingdom of Granada, the locality was left empty, and it was repopulated by Christians.

The fertile soils that have given these lands their fame still persist in its wide lowlands. In the image, Exfiliana and Alcudia, almost together, as they were centuries ago, according to historical sources.

This thus began a strong Christian tradition. Its patron saints are the Holy Martyrs Saint John and Saint Paul (both former officers of the Roman army, who suffered persecution by the Romans in the times of Constantine the Great, being martyred by their conversion to Christianity and decapitated in 362) and through the commemoration of the Virgen del Rosario (Our Lady of the Rosary), the victory of Lepanto (that took place the 7th October 1571) when it was traditionally celebrated.

It is not surprising then that this small village was to be home of one of the top representatives of the religious art of the Late Baroque period: Torcuato Ruiz del Peral, the author of the sculptures of the saints located in the choir of the Guadix cathedral, and that of the Virgin of Santa María de la Alhambra, among many other important works.

In the 16th century, the small village is named Ysfilyna and two centuries later, in 1750, it is described, according to the Catastro de Ensenada (Ensenada’s Land Registry), as a “small town of 80 houses and 5 grinding mills. The inhabitants of the municipality used to earn their living by cultivating orchards, vineyards, poplar groves, mulberry and other fruits trees, chestnuts, and some olive trees as well as by the production of silk.”.

Returning to the historical natural environment of this land, we find how it is described in many medieval sources that refer to the beauty of this setting. Historian and soldier Luis del Mármol Carvajal, born in Granada in 1524, wrote: “the river, going down from Sierra Nevada finds Alcudia and Zalabin and Ixfiliana… with very fine groves in the banks of the rivers, which waters throughout the orchards and plantations of the fertile plains, in which apples of great fame were produced, as well as the apricots, registered in the Castilian proverb books as ‘the apricots from Exfiliana, if they do not fall today will fall tomorrow’.”

A bird’s-eye-view of the valley allows us to see the variety of its geographic composition, which alternate cultivated meadows, pine groves and river courses.

As for Alcudia, it is believed that its traces its origins to prehistoric times, when it was located opposite its current setting, on the other side of the valley where the Zalabí hermitage dedicated to Nuestra Señora de la Cabeza stands now. However, it was not until the 8th century, at the dawn of the history of al-Andalus, that first Muslims, the Yund Syrian family, settled here. This tribe managed to escape Damascus after the massacre of the Umayyad family members, at the hands of the Abbasids, the rival dynasty.

From this massacre also escaped the young prince who later became the caliph Abd-er-Rahman I, who started the Umayyad saga in al-Andalus, marking the most brilliant period of Muslim Spain. Yet, the population of Alcudia shifted in the 10th and 11th centuries to be composed of North African Berber groups, and other tribes’ groupings like the Kalbids (a Muslim dynasty of Yemeni origin who came from the Emirate of Sicily) Alcudia begun then to be known as Alcudia al-Hamra, Alcudia the red one, in an allusion to the colour of its land.

The castle of La Calahorra, the most medieval symbol of Middle Ages in the plains of the Marquesado was built in the 16th century over the rests of an old Arab fortress.

It is located on top of a 1.200 metres high hillock that overlooks the Marquisate of Cenete, it constitutes the first work in Spain with Italian artists and material from Italy, whose interior contains one of the most beautiful examples of the Renaissance architecture.

After the conquest of the Kingdom of Granada by the Catholic Monarchs, and once it was integrated into the Crown of Castile, Alcudia earned acknowledgment by its fine farm production, and because of the advanced standard of living for daily life of the time: there was water in every house, its inhabitants could benefit from a myriad of communal goods, and it was also popular because of the fame of its baths, which became nightly parties mainly in wedding celebrations.

Throughout the Middle Ages, the area remains imbued with an unmistakable medieval tradition. We are acquainted with figures like the Marquis of Zenete, or the acclaimed Granadan admiral Álvaro de Bazán (whose most important campaign took place in the Battle of Lepant) had properties in the Valle. This admiral had a vast property in Exfiliana, about which it is said his orchards had great fame due to their highly productive agriculture.

Spanish politician Pascual Madoz (1806-1870), who gave name to his famous Diccionario geográfico-estadístico de España y sus posesiones de Ultramar (Geographic and Statistic Dictionary of Spain and its overseas possessions) known simply as Madoz’s Dictionary,describes in it: “outside the walls of Exfiliana towards the east, in the site known as Zalaví, that is to say the place which already was a population nucleus in the times of Mármol Carvajal, it can be even proven how important and close were the four nuclei, as they were almost united.”

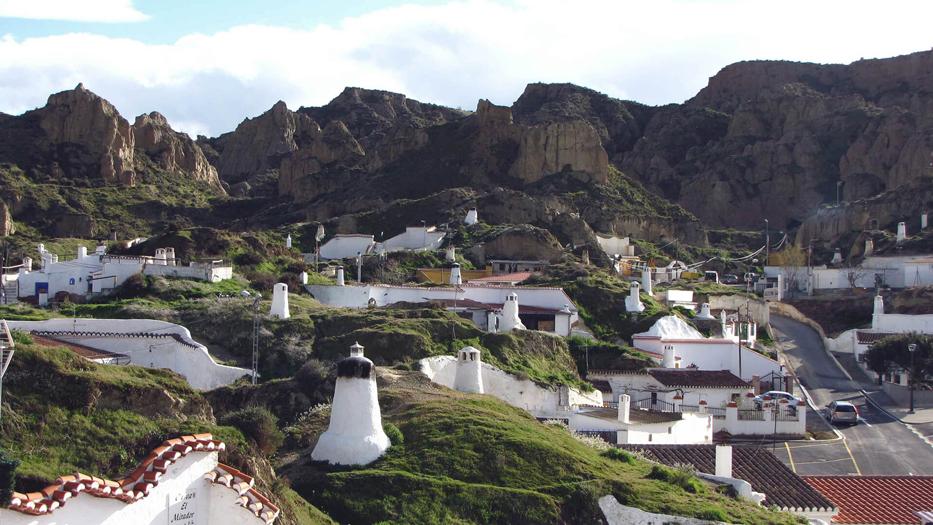

What adds most to this primitive landscape’s distinctive character is the way its fertile plains, poplar, and pine groves alternate with the clay formations of its hills. They have been and still are, ideal for troglodyte habitations, so common in this area.

Hills pierced with this cave-habitations are very common in this area, and nowadays they are a very sought-after housing alternative, whose construction has grown very much.

The date caves began being used as housing in this region is uncertain, although some theories point out that its origin might go back to times when the Berber tribes settled in the area, since the oldest caves ̶ which originally were used as fortresses ̶ were from the late 10th and early 11th century. During the Almohad period (12th-13th centuries) their use diversified, and they served both as defense and housing units. The last Hispano-Muslims who inhabited these lands, the Nasrids, started to use them for residential purposes, just as they are used nowadays, and there is evidence of the existence of inhabited caves when the Catholic Monarchs arrived in Guadix in 1489.

It is this typology, unique in Europe, which today represents one of the greatest appeals of the area, attrackting many visitors. Living in a cave entails a fabulously ecological housing possibility, and even though its benefits are known since times of old, in our days it is highly regarded, mainly because of its sustainable conditions. As for their climate, a temperature inversion occurs in its interior, which results in a cool temperature in summer and a warm one in winter.

The building of caves is possible thanks to the softness of clay. They are dug out along the slopes of hills, canyons or ravines departing from a vertical plane to continue piercing galleries on the horizontal making as much branches as you want. Resulting rooms are coated with mortar, and then whitewashed. Smoke is evacuated through chimneys that are built by piercing the hill vertically, to then appear at the surface, which gives the scenery a surreal appearance. Access takes place through a wooden door, sometime split into two parts (the upper serving as a window), a tradition of Morisco origin.

Regarding the rise of this type of housing in our days, architect Meritxel Álvarez drafted a project in 2013 about the interpretation of this characteristic habitat, from which we can extract interesting information:

“People have applied very simple and intelligent techniques to benefit from the favorable conditions that this environment offers to create this singular habitat. On the other hand, the Mediterranean climate, predominantly continental and with tendency towards aridity, determined the natural framework in which it was possible to dig these dwellings. About construction, we can consider it a vernacular architecture, as it is a way of habitation brought about by the inhabitants of the region and in a given period, by means of their empirical knowledge and experimentation.

The fact of being built using materials available in the surrounding environment achieves the objective of generating microclimates to obtain a certain degree of thermal comfort and hence to minimize the conditions of extreme climates. From today’s perspective, it is also important to consider the socioeconomic role played by a bioclimatic and sustainable architecture integrated into the environment and landscape.

Considered as non-aggressive, this housing represents an important legacy concerning popular architecture, and its residential use has led to such reappreciation that it has moved from being considered a type of housing for the poor to be a bioclimatic housing that meets today’s needs and enjoys a promising future. Therefore, together with the traditional residential use, the tourist development of caves has become over the last years a reality, with a potential differentiator that makes it one of the major attractive of the sector. Despite not being possible to quantify the process, we can ensure that particularly over the last twenty years ̶ from the 1990’s ̶ the proliferation of these dwellings has taken a great leap ahead. This has been possible because of the positive perception towards this type of housing by the population and the political support given by local authorities.”

Located between Alcudia de Guadix and Exfiliana, “TROPOLIS” is an interpretation center hosted in caves where different rural activities are organised around five paramount presentations: BREAD, WINE, CHEESE, CRAFTS and TROGLODYTE HABITATION.

The increasing Interest on rural and cultural tourism has well placed settings of this kind in front of the lists of “getaway destinations”: its landscape telling its long history, its gastronomy, the high quality of its farm products, long recognized, together with the welcome of its people and its genuine traditions, make of this valley a place worth being enjoyed.

Ana Carreño Leyva

El legado andalusí Andalusian Public Foundation