The discovery of Granada by the French Romantics

By Youenn Rault

Travelling by the first French to visit Spain was for a military purpose: the Napoleonic Wars.

Yet, they found an arsenal of poetic inspiration that was to nurture the spirit of the Romantic artists who never ceased visiting Spain, especially Andalusia.

Spain, but specially Andalucía, have aroused a true passion among French Romantics, with Chateaubriand and his Last Abencerrage, for instance, and also Merimée and his Clara Gazul’s Theatre, his celebrated work Four Lettres from Spain, and above all Carmen, which became a legendary figure. This includes Victor Hugo, who besides his theatre and numerous poems about Spain, has left us the tale Travel to the Pyrenees and Alps.

The list could be endless, and it shows the real obsession with this country. But what is the reason behind the interest of the French towards Spain? How is travel come to be combined with creative work? What will be the resulting image of Spain and specially of Andalusia they would create, and specially of Andalucía? Is the Romatic impact still visible?

The first French people began to reach Spain in the first years of the 19th century, when the country was devastated by the Independence War; they were soldiers who cared little for the narrative of their journey. However, this military presence inaugurates the first wave of travellers, writers and poets determined to describe Spain.

This journey, this “search of the absolute” will become another search: that of the “lost paradise” −Oriental, yes, but also poetic.

Focusing on Granada, the vision that will be created departing from this Romantic drive to contribute to the making of more than a few myths and legends, to a poetic vision that will lead to common criticism and, finally, to failure.

How did these travellers get to Spain? What drew them to visit the country? Who were the first to describe Spain?

The approximate context of the Romanticism that was experienced in Granada is framed within the political, social, and cultural situation of Spain in the early 19th century, when the initial wave of French people arrived, which not only included soldiers, but also literary figures, members of the aristocracy and persons of a high social rank. Figures such as, among others, Jean de Rocca, hussar and second husband of writer Madame de Staël, and Chateaubriand, at the time Minister of Foreign Affairs. Immersed in the war as they were, the vision they offered was different, which despite being more technical than literary, it was also personal, a factor that appealed to the Romantics.

JJean de Rocca, a member of the prestigious corps of hussars, reflects this in his account Mémoires sur la guerre des Français en Espagne, (Memories of the French war in Spain)where both thoughts and feelings meld: «The sky in Andalusia is so pure and clear that you can sleep in the open air almost throughout the year; in summer, and sometimes even in winter, men sleep under the porticoes. There are many who, lacking money, travel without any regard for finding accommodation every night; they either bring their own foods or buy them for the women who prepare them for passers-by in stoves at the entrance of big towns or in the public squares […]. In Andalusia, more than in any other region of the Iberian Peninsula, we find at every turn the Arabs’ traces and memory, being the singular blending of Oriental and Christian customs that distinguishes Spanish people in particular with respect to the European people. »

If travel embodies one of the main subjects of Romanticism, it is due to the incorporation of aspects such as the spirit of freedom and adventure, the discovery of the unknown and the exotic natural landscapes that inspire deep emotions to the artist. . In southern Spain in particular, the remains of ancient times, of cultures such as the medieval or the Oriental, which they did not know but they were about to discover, are meant to be the source of literary inspiration, the counterpoint to classical uniformity and the rationalism of the preceding centuries.

To the left, a portrait of Jean de Rocca, in his hussar uniform while serving in Napoleon’s army during the Spanish War of Independence, on the subject of which he wrote Mémoire sur la guerre des Français en Espagne (Memories of the French wars in Spain). He was married to Mme. De Staël, who introduced German Romanticism in France. She was a pioneer feminist who advocated education for women. Her “salon littéraire” in Paris was renowned and her ideals on monarchy caused her expulsion from France by Napoleon, who considered her a disadvantage for his politics.

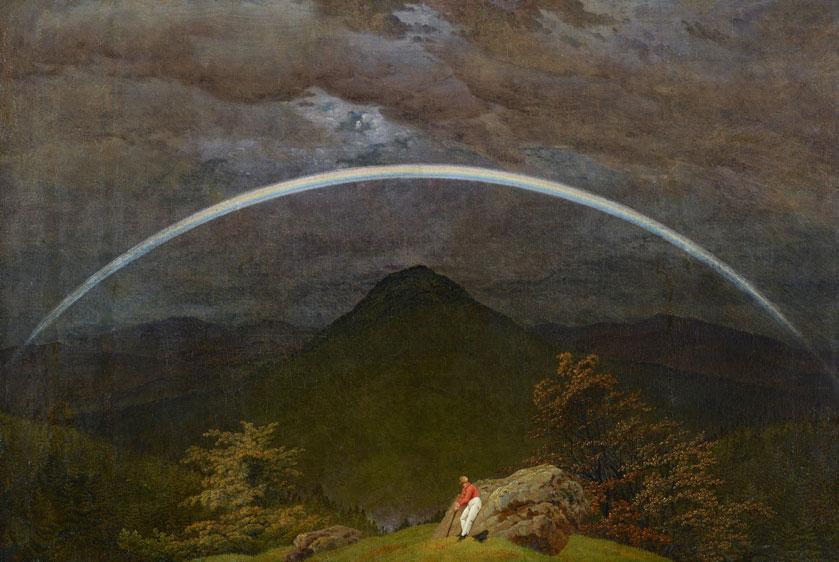

Right, a clearly Romantic painting of the great writer and driver of French Romanticism, the Breton François-René Chateaubriand. He was a Napoleon’s Minister, despite he was initially against the revolutionary process, since he was a supporter of monarchy and a member of aristocracy himself, for which his family was executed and he was also persecuted.

The melancholy of History

History and travel hence occupy the same creative space, but it is history that is the heartbeat in the writing of the Romantics. The work of writing draws out over the time, and hence its relationship with History takes different shapes.

Before undertaking a journey, the author forms an idea of what he is about to discover by means of what he has read, but also, based on what the culture has transmitted. During his sojourn, the author is in constant contact with history. Every monument, every music, every landscape is new to him.

The writer and French Hispanist Martinenche (1869-1939) writes, in his chapter entitled “Les Maures et Leurs Monuments en Espagne” (“The Moors and their Monuments in Spain”) from his work Propos d’Espagne (On Spain): “Of all these wonders that have flourished on the ground of that picturesque Spain […] Arab monuments are perhaps the most attractive. They possess for us the enchantment and the sweet melancholy of lost civilizations”.

A physical or a symbolic journey?

History is one of the many reasons that motivated the Romantics to travel to Spain, but this becomes more specific when the fascination for the East that started to take place in Andalusia uses the mixing of cultures; the journey offers an itinerary between East and West. In Dumas’ work Impressions of a Trip, we can read: “To travel is to live in the absolute fullness of beauty; it is to forget the past and the future in virtue of the present; it is to breathe deeply, to enjoy everything, to seize creation as if it were something that belonged to us. Many have passed in front of me, or I have passed in front of them while they have not seen what I have seen there, they have not understood the account I have been offered, and by their return they have not brought the myriad of poetic recollections that my feet have appear by removing, sometimes barely, dust of times of old”.

The Spain they knew up to that moment by means of books was a Spain devout, heroic, and picturesque that they considered Romantic par excellence because it kept the Oriental and Medieval essence that no other European country could offer. The word “Spain” became magic for these authors. Chateaubriand exclaims: «How my heart was beating by approaching the coast of Spain! » In 1865, Gautier would even write: «we are ready to depart as soon as one pronounces that magic word: Spain.» That unexpected treasure of the Orient in Spain would make it into the beacon of the Romantic destination.

For Romantics, nature, rather than culture, is what really generates a true passion: spectacular landscapes, natural sceneries with grandiose monuments and vestiges of the past are the alma mater of their inspiration. Their personal experience on the ground is the heart of the narrative, which nurtures and gives sense to it. But it is necessary to elaborate carefully the way in which the account is told so as to be suitable for publication. Travel literature constitutes a literary genre of its own which is allowed to consider culture, customs, and common heritage while also taking into consideration critics to the establishment and society. According to the famous author of the Tales, Hoffman (1881), “French people were precisely the first ones, and later the most diligent in proclaiming the beauty of Spain. It was their books, credible or not, that drew the attention of Europe and the entire world.”

The contemporary author Nikol Dziub writes in 2015: «Awakening dormant stories and listening the people’s voices: that is the task of the Romantic travellers, who take into consideration the ancient history of the region and modernity as a whole. This way, journey and history have a double aim, which is unique to the poet, the writer, whose purpose is to convey their experience, and that of the historian who “awakens dormant consciences” […]. Orientalism then become rapidly one of the main characteristics of this Romanticism that spreads in places like Seville, Córdoba and, above all, Granada. What is translated in the Romantics texts is an authentic “alchemy of the word.”

In search of the lost paradise

Romanticism is shelterd, as far as Granada concerned, in the legend of the “Moor’s last gaze” to create here a myth, from which is born the true myth of Granada, “the eternal nostalgia”. When Chateaubriand talks about the Alhambra, he exclaims: “Over there rose a tower looked out by the sentinel in times of wars between Moors and Christians, over here appears some ruins whose architecture announces its Morisco (sic) origins, one more object of pain for the Abencerrage.”

Haunting Granada

The Romantic image of Andalusia is sometimes limited solely to the city of Granada, as shown in the many writings in which the traveller imagines it, even before visiting it, as an extraordinary place. The prolific French author François Quinet (1803-1875), writes in this respect: “Everything produces the effect of the intoxicating plants from the Orient […] I imagine that the dizziness of opium or hashish can give an idea of this somnambulism of the soul into which the Alhambra invites us, as they dwell in the same territory of dreams and contemplation.”

Granada, the Vega (Fertile Plain) and the Alhambra are then assigned status as a true, ideal place exalted by the Romantics, who find here an “Eden”, a source of “the sublime” that will breathe life into their accounts. Is this idea of “Eden” located by the Romantics in Nasrid Granada and the Alhambra? Is it a coincidence or is it due to the intervention of the “magic” of Granada? In any case, what their writings convey is the real evocative power of Granada and of a symbolic monument such as the Alhambra.

The writer Nikol Dziub, adds: “The journey, then, as a search for infinite, is transformed into an absolute truth; the landscape forms part of the cosmos that is the extension of the poetic Self, that is, revealed in the figure of the “writer-creator.” The Romantic writers see in Andalusia a sort of last refuge of Nature, a place where not only literature of past times, ruled by orality, can return −so that the transmission of knowledge is not produced by a particular author, but by the people, who are at the same time receiver and emitter − but also the mythical and glorious age of religious conviviality. The Andalusian geography incorporates both the scientific coordinates and the mythical elements inherited from the legendary al-Andalus and the Orient.”

CodaAlmost two hundred years later, Martinenche’s words, for whom the monuments from al-Andalus “possess for us the charm and sweet melancholy of lost civilizations”, also show the deep mark left by al-Andalus and the way of life and receiving this artistic and historic legacy. While it is true that the Romantics were the ones truly pushing for this melancholic and lyric image of the Hispano-Arabic heritage, nowadays we do not stop to reflect on its importance in our culture. What is more, we might wonder if the Andalusí culture has really “disappeared” as Martinenche said. Tourism may be the most effective proof of a living and present Andalusí legacy in Andalusia in general, and in Granada in particular, which breathes an undeniably Oriental atmosphere. |

By Youenn Rault

Cultural Manager.

Maison de France, Granada.