Montefrío, the horizon as a limit

“I said: How about Íllora and Montefrío? He answered: A village leant [on the other one] side by side, like colleagues who get on well. It is a source of excellent wheat, and a rich hunting ground. Both villages recline in rolling hills, so some houses are in the upper part and others in the lower one. There are plenty of animals. It is pleasant to live in them unless the enemy attacks their fortresses”.

Ibn al-Khatib, Mi‘yár al-ijtfyár. Circa 1390.[1]

[1] IBN Al-JAṬĪB: Mi’yar al jhitar fi dilr al-ma’ahid wa-l-diyar. Ed. and trad. G. Chabanas. Rabat, 1977.

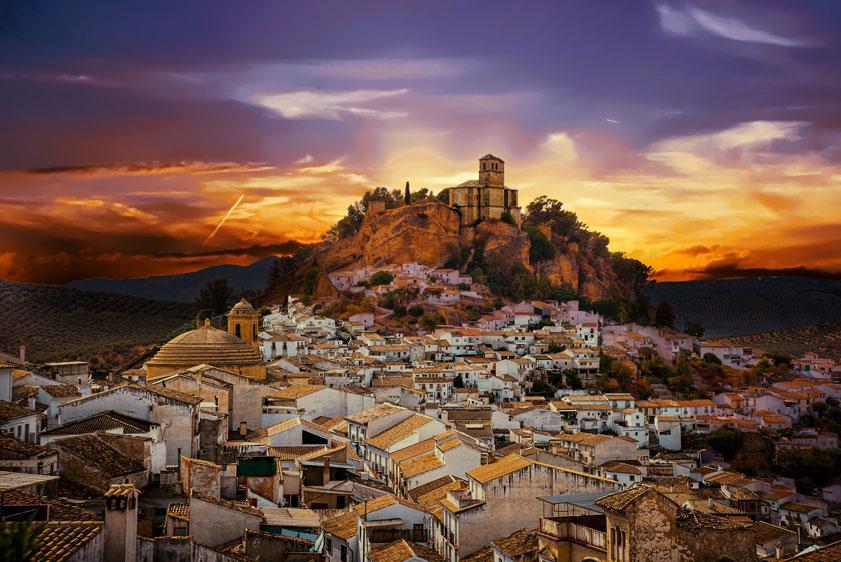

Montefrío, one of the main attractions on the Route of the Washington Irving, appears on the horizon as we cross a mountain pass in the Beticas mountain range. Clinging to its cliff like a lichen, its geographic placement and its changing surrounding landscape foretell its arcane history: crags and ridges, the wide flats of its fertile plain, hillocks and valleys, combined with poplar and pine groves, seem to explain why this enclave was chosen to be an area for settlement since the dawn of history.

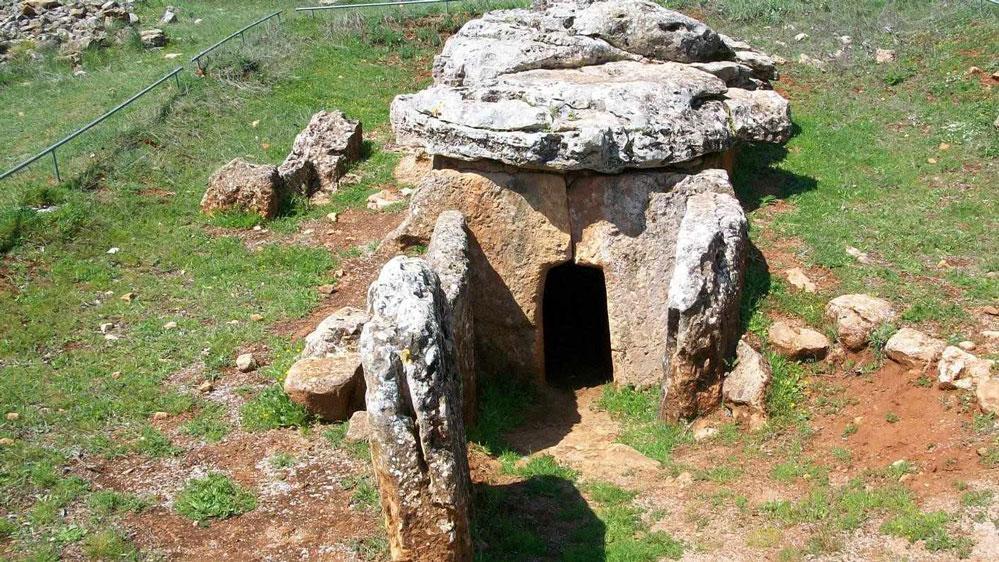

This is confirmed by the myriads of archaeological remains in the area. To the prehistoric settlements, and from subsequent periods, we must add the regular urban centres in the mountain passes typical in the early times of al-Andalus.

Peña de los Gitanos, showcasing the existence of settlements from the Neolithic era to medieval times.

The late antique or high medieval settlement from before the arrival of the Arabs in Montefrío’s area is verified by the existence of a large amount of necropolis and populations at high altitude not only in the municipal boundary, but also in the vicinity of the old Nasrid castle in the area of the alcubilla (word of Arabic origin meaning water manhole), where graves and ruins of constructions have appeared.[2].

[2] Rafael J. PEDREGOSA MEGÍAS: Montefrío en Época Nazarí. Proyecto de Investigación para la obtención del D.E.A. Máster Oficial “Arqueología y Territorio”. Universidad de Granada, 2010. Inédito. Ídem: Guía histórico-arqueológica del Castillo y atalayas de Montefrío (Granada). Sevilla, 2011, p. 90. Ídem: “La evolución de una villa nazarí de frontera: Montefrío. Antecedentes, configuración y transformación tras la conquista castellana”. Revista del CEHGR Nº 24, 2012, pp. 73-103.

During the Middle Ages, Montefrío played most of the time the frontier role that history had assigned to it. Defined by its geo-political function, its castle-fortress has surveyed the neighbouring mountains and roads that leads to Granada’s borderlines in the most revulsive periods of its chronicle. Its toponymy speaks to us of its different ages; from Roman times it keeps Mons Frigidus (Monte-Frío=Cold Mountain), and after being Islamized it was named Hisn Montefrid. La hipótesis que apunta el arabista Seco de Lucena es la de origen árabe Muntfarid (Monte Único). Spanish Arabist Seco de Lucena’s hypothesis is that its origin comes from the Arabic Muntfarid (single mountain).

The origin of Nasrid Montefrío dates back to the end of the 11th or early 12th century. Its main source of livelihood was livestock and a very little developed agriculture, which the Mozarab population had inherited from the late Roman period.

Although its population had Islamized gradually over the 9th and 10th centuries, it nevertheless took part in the revolts with the Muladis (Christians converted to Islam) mainly in mid-11th century. This is the reason behind the fortification of what was then the village.

Rafael G. Peinado Santaella, historian of the University of Granada and expert in Medieval History is a native of this superb Granadan enclave. With him, we will trace back its history from which, being so dense, we will just address some aspects of its Andalusí period and the vicissitudes that came to pass for the population after the Catholic Monarchs’ conquest of the Kingdom of Granada.

Partial view of the pastures in the Peñas de los Gitanos area.

“The peace brought by Abd-er-Rahman with the Umayyad caliphate had led to the abandonment of these defensive populations at high altitude.We have two areas which have been studied, like Peña de los Gitanos and the nearby El Castillón, and the temporary settlement of Los Castillejos. Findings in this area belong to Nasrid times, as testifies the Medieval glazed ceramics found (Arribas Palau and Molina González 1979), as well as the Muslim presence as revealed in the burials excavated and the diverse ceramic artifacts (Alfonso Marrero and Ramos Cordero 2002). The absence of signs of destruction or fire appears to show that this process occurred gradually and peacefully in El Castellón, being also probable that its inhabitants gathered with other communities and that even the new population remained in La Villa’s hill. The hypothesis expands in relation to this last idea, although in later centuries no other remains of Arab constructions have been found in Montefrío except those of La Villa, while its chronological data belongs already to the Nasrid period”.

Although the author of Anales de Granada,(Granada’s Annals – 17th century), Francisco Henríquez de la Jorquera tells us that about its population “In Nasrid times Montefrío was a large community of brave frontier Muslims”, Historian and Archaeologist Rafael J. Pedregosa Mejía states: “The population density was scarce, and what existed was a conglomerate of alquerías (farmstead) like those in the area of Cortijo (farmhouse typical from Andalusia) de la Cruz, of Marcos and the area of Cortijo de los Moriscos, Torre de Nunes and the ones that existed where nowadays is placed Villanueva Mesía. In the same way, it is likely that one of these alquerías might have been within the perimeter of the castle wall, which was to be converted into a military compound after the conquest of Alcalá la Real by Alphonso XI in 1341″. Its entire environment depended on defense purposes; the alquerías were also aimed at monitoring the border lines, which fluctuated with the rythm of the military advances and withdrawals from both sides, protecting the roads arriving from Priego or Alcalá la Real, paramount places already in Christian hands. And Rafael Pedregosa adds: They also controlled the passages toward Granada fertile plain, mainly through the Arroyo (stream) de Milanos and the Arroyo de los Molinos, as well as the natural passages in the area of Las Angosturas and the Sierra de las Chanzas, in the limits of Montefrío.”

Archaeologist and jurist Manuel de Góngora (Tabernas, Almería, 1822 – Madrid 1884) offers to us the first news about Montefrío’s history in his work Prehistoric Antiquities of Andalucía, presented in 1868:

“Coming from the Cortijo del Castillón, the traveller cannot neglect visiting, in the southward direction, a hillock cut by very high mountains that decline to the south. There we discover vestiges of walls and, inside the perimeter, very clear remains of buildings. In the side facing the cortijo and in the plains by their sides, there is no doubt that a [sic]village was there. The eastern slopes of Cerro del Castillón and both sides of the path leading to Montefrío, are materially strewn with sepulchers. I ordered to excavate, and we found skeletons, and in them mugs in clear colour, a copper earring, another one in bronze, and a piece of iron I could not say what was its use…”

To this, other studies followed, showcasing the importance of this territory that started to be inhabited since time immemorial. But it was not until the Middle Ages when Montefrío was at the forefront of the events which have reached our times thanks to the research of scholars and historians, both old and contemporary.

Pascual Madoz, in his Diccionario Geográfico-Estadístico Histórico de España (Geographic-Statistical Historical Dictionary of Spain) (1845-1850) described the environment as one provided by “a vegetation of oaks and holms oaks”. Today, few of the primitive holm groves remain, and chaparral and kermes oaks hardly survive. Flora, conditioned by the geology of the Medio Sub-Baetic mountain range grows sheltered by the soft rocks that alternate with the wide extensions of olive groves, and other characteristic cultivations of the Mediterranean climate: very dry in summer, with long cold winters in which rain is scarce.

In the early 20th century, Manuel Gómez-Moreno added information in his study Monumentos Arquitectónicos de España, (Architectural Monuments in Spain), and by mid-century Cayetano de Mergelina undertook different excavations which led him to differentiate four historic periods in the area: Neolithic, Iberian, Visigothic and Arab.

But let us return to the Andalusí period. Upon the Muslims’ arrival, and being an important defensive post as it was, as well as its neighbouring lands, all provided with strong fortresses, the village, walled, sits on a level surface of the slope in the rock crowned by the castle, defending and controlling every possible access to the Nasrid emirate.

Remains of a stretch of the Arab wall.

The castle is considered one of the main fortresses of its time. It was built after the consolidation of Montefrío as a major border post, its urban layout following the same patterns as its adjacent frontier lands, whose mission was eminently defensive. It was built in the Nasrid period by the same constructor that built the Alhambra after the Salado battle in 1340 [3] and after the conquests of other important nearby posts like Priego de Córdoba, Alcaudete and Alcalá la Real, the northeast frontiers of the Kingdom of Granada were reconfigured and king Yusuf I founded, or rather rearranged Montefrío, according to Ibn al-Khatib’s chronicle. The castle was part of a chain of fortresses which included those of Íllora and Moclín, complemented with an ensemble of at least fifteen watchtowers (Cabrerizas, Anillos, Espinar, Sol, among others) that managed to control all accesses using visual signals.

Despite archaeology that has proven the existence of remains from the late-Roman period in the center of the present village, there is no evidence that the castle (hisn) was built in Nasrid times on top of an earlier one. Its location counted on the huge advantage provided by the land’s topography, and it was placed in the middle of two streams, that of Fuente Molina and Cruz Gorda. It had two separate precincts: the alcazaba (fortress) in the upper part, and the village itself in the lower one. This pattern was followed by other nearby villages: Moclín, Castril o Colomera, like so many other Andalusian villages and towns that seem to have a castle performing like a sentinel to watch over them.

In Nasrid times the village of Montefrío had the fortress precinct, a walled suburb to defend the population against siege. The only remains are a reservoir, a silo or bunker and the remains of a stonework tower. In relation to the existence of gates that might have pierced the precinct, a 16th-century neighbouring census records that one of them might be in a current place known as El Fuerte, located next to the hermitage of Saint Sebastian. This was built in the 16th century in the present Callejón de Fuerte, so called for its being part of the castle’s defense. Village elders recall the existence of some remains in the fifties, as do some names in relation to the gates in the urban layout, like the Puerta de Alcalá (for being oriented to the road that led to the neighbouring Alcalá la Real).

[3] The battle of El Salado was one of the most decisive battles with the last Maghreb kingdom, the Marinids, who attempted to get inside the Iberian Peninsula, whose army was defeated thanks to the union of the military forces of Spain and Portugal. In this phase of the conquest by the Castilians, only the Kingdom of Granada remained.

Montefrío and its church-castle.

How did Montefrío react before the relentless victory of the Christian armies, now on the threshold of the Kingdom of Granada? What happened to its population over the next centuries? Rafael G. Peinado tells us:

“The village of Montefrío surrendered to the Catholic Monarchs on 25 June 1486 after the fall of Íllora and Moclín. As also happened to other villages in the mountains region, surrender entailed the loss of the population’s real properties and forced migration with destination to Granada, of course leaving weapons and provisions behind. The population vacuum was filled with a bunch of Castillian warriors who arrived under Commander Pedro de Ribera, head stableman of Queen Elisabeth I. Almost four years later, by means of a card dated on 28 February 1491, the Catholic Monarchs decided to undertake the repopulation and they appointed the people in charge of distributing the lands and properties that belonged to the Nasrids. The repopulation task was in hands of around one hundred families, but we do not have detailed knowledge, for the Libro de Repartimiento ̶ where the changes of properties and names, the social status and the origin of the new owners were registered ̶ has not survived.

Just two months later, the Catholic Monarchs pawned the village and its fortress to Don Alonso Fernández de Córdoba, lord of the House of Aguilar and first Marquis of Priego, as a guarantee to repay the eight million maravedís , in money and grain, that the Andalusian nobleman had lent to the Crown for financing the war of conquest that started in 1482 and ended with the capitulation of the capital city of the Nasrid emirate by city in late November 1491.

One day after this endeavour, the monarchs empowered this nobleman to deliver civil and military justice in the place, hence giving way to a lordship government that left fond memories in the inhabitants of Montefrío. At least, this is what can be deduced from the statement made in 1558 by the witnesses in the process that the village undertook to migrate out the jurisdiction of Granada’s municipality.

Urban promenade at the site of the ancient cemetery.

Because, actually, after a long process, in 1531 the city of Granada repaid the heiress of the first Marquis of Priego the eight million maravedis her father had lent the Castilian Crown, and also regained the jurisdiction of the village. The “Lords Granada”, as the councillors of Granada used to be entitled, did not hesitated in acquiring properties in the municipality and even making reserved pasture spaces for the exclusive use of their livestock. This gave rise to social repugnance from the people of Montefrío, who could not attract customers, being them mainly poor people (shepherds and “apaniaguados” [4]) who were mainly the ones that undertook such outrages.

From this year of 1531 on, a new era marked by the increasing productive development started. But it is probable that this had taken place ten years earlier, if we take for granted the news, around 1521, whereby the privileged tax status that the village had enjoyed since 1487 had been reduced as an incentive to attract new settlers. A letter from the Emperor Charles V, dated on the 31 October 1531, is in fact very significative of this. In it, the mayor of Granada was ordered to be informed about the convenience of demolishing the fortress, in response to the request from the council of Montefrío made to King Charles as a result of its poor state of conservation, and hence its defensive uselessness, stressed by the fact of not being a border village any longer and being now located among villages whose brotherhood would be benefited from its demolition. All that would favour the demographic growth to up to five times the number of its neighbours, which might be more than five hundred.

[4] Servant paid through room and board by the employer.

Church de la Encarnación whose unique structure has its parallel in the structure of the Agrippa’s Patheon in Rome. Construction began in the late 1700s and was completed in the 19th century.

It was at those times when the parish church renovation works and its ultimate enlargement we know today was undertaken, thanks to the increase in production and population which contributed to favour both to diocesan coffers and the “fondos de fábrica” (a fund created for new constructions purposes) by means of the ecclesiastical contribution or diezmos. [5].

In the transition from the first to the second half of the 16th century, Philip II saw an opportunity in this buoyant economic situation to help the ailing Royal Treasury, by allowing Montefrío the independence of Granada by paying a substantial amount which its villagers were ready to pay. Although, in the end, it was Granada’s municipality which paid the two million and a quarter, hence keeping the feudal power over Montefrío’s people”, concludes our historian.

The story of these villages meets us while we walk around their streets and outskirts; and it is then when we understand the reasons for the setup of their location, the outlines of their lives, the links with their fellow villagers through their architecture, music, legends, their places of worship, their literature… all that embedded in a landscape that speaks volumes.

Not in vain, in 2022 Montefrío was rated by National Geographic as “one of the 10 towns with the best views in the world”.

Ana Carreño Leyva

El legado andalusí Andalusian Public Foundation

[5]The ecclesiastical contribution made to the Church consisting in the payment of the tenth part of normally grain production or other agricultural goods.

|

BIBLIOGRAPHY @rqueología y Territorio nº 8. |