Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, wife of the British Ambassador in Constantinople in 1716, was the first western woman to visit the private rooms of the Ottoman imperial harems. In her correspondence with family and a selected list of friends −including King George II’s wife−, she described those exotic and sensual environments which were to set running the imagination of the romantic travellers. In 1763, a year after her death, she published her book

In 1716, after Mary announced to her friends and family that she was to accompany her husband to Turkey, many thought she was insane. The fact that a lady of such a social position with a bright literary future ahead of her would risk her life −and that of her four-years-old son− to travel to the “infidels’ lands” was something hard to understand. Yet the intrepid traveller enjoyed her stay, learned Turkish, visited places no European had ever walked before, befriended the Sultan’s daughters, and maintained contact with Turkish ladies of the highest nobility.

In a letter dated March 1718, she described at length the lavish attire of her host, Princess Fatma, in a account that resembles a passage of One Thousand and One Nights: “Round her neck she wore three chains, which reached to her knees; one of large pearls, at the bottom of which hung a fine coloured emerald as big as a turkey-egg […]; another consisted of two hundred emeralds, close joined together, of the most lively green […]. But her earrings [sic] eclipsed all the rest: they were two diamonds shaped exactly like pears, as large as a big hazel-nut [sic]”.

Lady Wortley Montagu became a very famous character in England of the early 18th century not only because of the quality of her poems and her sharp satires, but also for her hazardous love life. She challenged her father by secretly marrying the man she picked, his extravagant and crazy son becoming the heaviest burden on her. She also was at the center of fierce debate with the most outstanding intellectuals, among them the poet Alexander Pope. In love in her mature years with a young and handsome literary man from Venice, she abandoned her hectic London life and left to Italy to live there permanently. Her daughter, Lady Bute −born during her stay in Istanbul−, frightened about her mother’s eccentricities, decided to burn her mother’s most intimate diaries in order to a greater scandal. Luckily, we have still her letters written during her stay in Istanbul, which being forward-looking, she left in the hands of a Dutch reverend to be published after her death. They constitute a unique historical document to know the splendour of an empire that was gradually losing its power and possessions in Europe, despite the court of the whimsical Sultan Ahmet III that upheld all the luxury and pomp of the old days.

A rebel spirit

On May 26, 1698, a baby named Mary Pierrepoint was born in the elegant London district of Covent Garden. Her father, Evelyn Pierrepoint, Duke of Kingston, was a rich, handsome bon vivant aristocrat and member of the English Parliament for the Liberal Party. Her mother, Mary Fielding, was the Count of Denbigh’s daughter and she was related to the famous English writer Henry Fielding. Hence, the little girl came into this world in a healthy, influential and cultivated noble family which would mark her refined literary tastes. Mary lost her mother when she was only four years old, and her father, unable to raise his children, left them in the care of their paternal grandmother, Elizabeth, who lived in a house in the countryside near Salisbury. When their grandmother died in 1699, Mary and her three younger siblings moved to the splendid mansion of Thoresby Hall, in Nottingham, where the Pierrepont family had come from originally. The extensive park that surrounded the property −whose main home was designed by the most famous architect of the time, William Talman, no matter what it may have cost− had been part of the Sherwood Forest, the scenario of the epic feats of Robin Hood. However, what little Mary liked most in Thoresby was the magnificent paternal library, which housed thousands of volumes that she started to read with great enthusiasm. When she was thirteen years old, she already spoke French and knew Latin she had learnt by herself from a dictionary and a grammar book she always carried along with her. Thanks to Lady Mary’s portraits in picture galleries and museums, we know she was not a particularly beautiful woman, although she sounded attractive due to her sharp wit, elegance and strong personality. These were the attributes that in 1708 captivated a handsome and promising politician, eleven years her senior, named Edward Wortley Montagu. Being a cultivated man, clever, and one who loved travelling, he was no doubt a good candidate; over time he would inherit the earldom of Sandwich and the family’s properties. Mary’s father, however, would see no charm in the grim Mr. Wortley, and from the very beginning he opposed this relation.

On August 21, 1712, the impetuous young woman ran away from home to join the man she loved. She just took along some of her belongings, among them her most precious poetry books. She was aware of the scandal that her flight would cause and that her father would never forgive her. They married in secrecy within a few days in London, starting a new life in common that was not going to be easy. Not even her first son’s birth, Edward, on May 16, 1713, would change her husband’s attitude.

At the beginning of 1715 Lady Mary moved to live with her husband to a new home, this time in the upscale neighbourhood of Westminster, very close to St. James Palace and Parliament. At the time, the writer already enjoyed a great social success, and among her admirers were Voltaire and poet Alexander Pope, as well as Princess Charlotte, future Queen of England. However, those instants of happiness lasted a short time. By the end of that year, she contracted smallpox, which was wreaking havoc in England. In that turning point of her life, when her marriage was in complete decline and her health being still weak, she received some news that would seal her fate. In 1716 mister Wortley Montagu was appointed Ambassador to the Sublime Port, in Constantinople, and despite it was poorly paid, he accepted with pleasure.

The great departure

In early August, the diplomat and his family left London with much fanfare accompanied by an entourage of twenty servants. Travelling in those first years of early 18th century from England to Constantinople, through the Turkish dominions, was a dangerous adventure. Lady Mary would travel the usual way to reach the city of Vienna to continue in the middle of winter through the Balkans. They had to boldly take the challenge to face, among other dangers, the intense cold, the swine fever epidemics, the lack of hosting and the permanent threat of bandits. A year later after her departure, when the English lady finally reached the heart of the Ottoman Empire, she started to explore a world as unknown as was fascinating.

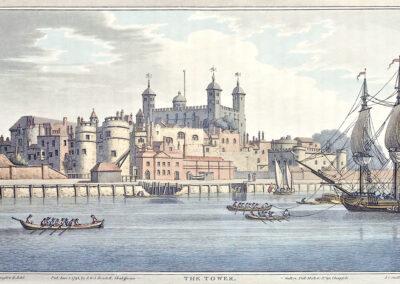

We know the details of her fearless crossing to the East thanks to the letters that Lady Mary started to write during her first stopover. In Rotterdam, on the 3rd August 1716, she describes to her sister Lady Mar; the trip on the sailing ship that they took to Holland, and how they had miraculously survived a terrible storm. Pleased to have endured this first trial without suffering “the effects of fear and dizziness, though, I confess, I was so impatient to see myself once more upon dry land” they reached The Hague, from where they departed towards Vienna in hired carriages.

In the days that followed, Mary faced exhaustion and all manner of inconveniences. In the “miserable” hostels they found along the way, it was, according to her words, it was advisable to pass the night in her clothes because “I had no mind to undress in a room where the wind came in from thousand places.”

After a short stay in the city of Hannover and a visit to the splendid Vienna, the couple continued on to Belgrade, where they planned to travel down the Danube by boat. But due to the pasha’s refusal to provide them a special escort, they were obliged to continue the travel by land, exposed to a plague epidemic that broke out in the region, staying in filthy inns. Ultimately, they reached the Bulgarian city of Sofia, which Mary found “one of the most beautiful cities of the Ottoman Empire, famous for its thermal baths, aimed both at entertainment and health purposes. It was here that the ambassador’s wife visited a Turk bath to entertain with her story her girlfriends in England.

In her letter dated 1 April 1717, once established in Edirne, Lady Mary recalled every detail of that first visit to a hammam: “ (…) Every woman attended au natural, that is to say, as we say in common English, entirely naked, without concealing beauty or flaws […] . Among them there were some whose proportions were like any of the goddesses painted by Guido or Titian’s crayons; they mostly had a glowing and white skin, only covered by their beautiful hair combed into many braids over their shoulders, graced with pearls and ribbons; they were the perfect representation of the figures in The Three Graces.”

The English ambassador and his wife were initially established in Adrianople, today’s Edirne, in the Turkish region of Thrace. They were assigned a palace in the Banks of river Evros in the embassies area, surrounded by orchards and fruit trees. From that moment on, the so-called Turkish letters the writer sent to her friends and family in England, described the ruling sultan Ahmet III’s splendour of the imperial court. Her passionate correspondence captures in detail when the sultan left the palace each Friday to attend Friday prayers at the mosque, the majestic ceremonies on the occasion of imperial births, the mosques’ architectural beauty, the opulence of palaces and the refinement of the harems where sultanas lived. Mary, who always was very coquettish, soon chose to wear the Turkish clothing and in a letter addressed to her sister Lady Mar she made an in-depth description her “lavish and flattering” apparel which made her feeling like an Oriental princess: “The first piece of my dress is a pair of drawers, very full, that reach to my shoes and conceal the legs more modestly than your petticoats. They are of a thin rose-coloured damask, brocaded with silver flowers. My shoes are of a white kid leather, embroidered with gold…”

On May 29, 1717, the couple moved to their new destination in Constantinople, a city twice as big as Paris. Sir Wortley rented a 17th century palace in the neighbourhood of Pera, where the diplomatic corps was lodged. The house had a large terrace, gardens and beautiful views over the Golden Horn with the Bosphorus in the background. At that time, Mary, who was twenty-eight years old, was few months pregnant although she did not mention it in her letters. All along, the English aristocrat was not satisfied to be just the ambassador’s wife/consort; whenever her social duties permitted and concealed under a double veil and a long gown, she discovered the bazaars, mosques and public baths astonished at what everything she saw.

(End of part one)