Münzer, a journey through Spain in the sixteenth century

PART II

In the year 1495, just three years after the Catholic Monarchs had conquered Granada, a German traveller, Doctor Hieronymus Münzer visited Granada. He left us an important chronicle about the newly Christian city.

The Austrian doctor’s open-mindedness is worth highlighting, as he was always ready to prevent unforeseen circumstances or surprises from invading his good spirits. This can be seen in the receptive spirit implicit in the descriptions he makes on most things he saw. So much so that he often meets without acrimony those circumstances outside of his familiar world, frequently behaving in a generous manner when it is time to offer praise. Besides, few are the occasions when his descriptions could have offended the sensibilities of people whom he observed. In relation to this, it will be simple to analyze his whole work to see how, even if he finds odd some of the Moriscos’ customs, he never disparages the lifestyle of this people in his pages.

Before reproducing some of the passages written by Münzer, it would be no bad thing to report certain deductions that appear after having analyzed his account as a whole, as it is, for instance, that the group of friends who were travelling had to make the most of their itinerary at full capacity. This meant spending both mornings and afternoons on their journey. We know that they rented horses along the route to travel from one place to another, a way of travelling that likely would have caused them not a few tiresome labours, but which nevertheless reveals and confirm to us that these young men belonged to privileged classes, for even among the medieval travellers there were social distinctions. Common to the humbler class of the population was travelling on foot, with horses being reserved for the most favoured classes, a means that, logically, doubled the medium average distance compared to those who travelled on foot without animals or the ones who, in any case, would transport merchandise by carriages drawn by oxen or mules. In Münzer’s case, we are surprised today when we see the vast journeys he was able to travel by using such a rudimentary means.

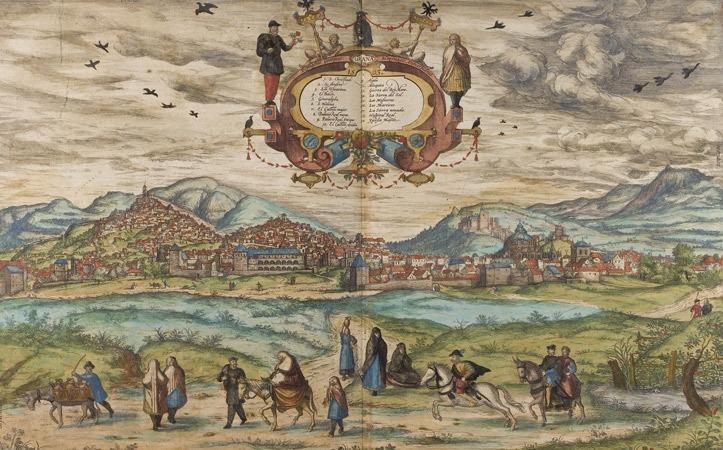

View of Granada in 1572. Civitatis Orbis Terrarum. J. Hoefnagel. ©Wiki Commons

“On 22 October, after midday, we reached the glorious and very populous city of Granada and, after going through a very long street amidst an endless crowd of Saracens, we were finally welcomed by a good inn. We took off our shoes inmediately, for we were not allowed to get in unless we were barefoot, and we stepped into the main mosque, more distinguished than the rest. There was mud owing to rain. It is all covered with thin mats made of white straw, like the base of the columns […]. Apart from the side columns there were orchards and palaces. We also saw many lamps burning, and priests singing the Liturgy of the Hours, which rather than chants one might believe were howls.”

His account about the way Muslims pray is uncanny: “In the city there are many other [mosques] smaller, whose number exceeds two hundred. In one of them we saw how they said their prayers bending and rolling over like a ball and kissing the ground and beating the chest upon the priest’s chant, begging God, according to their rites, forgiveness for their sins.”

Passing by a cemetery, he also notices the Muslims graves: “Don Juan de Spira, a credible man, told me that every Saracen is buried in his own, and new tomb. Graves are built with four stone slabs, so that one could barely fit in them. They are covered with bricks, so the cadaver does not touch the ground. Afterwards, the tomb is evened with earth.”

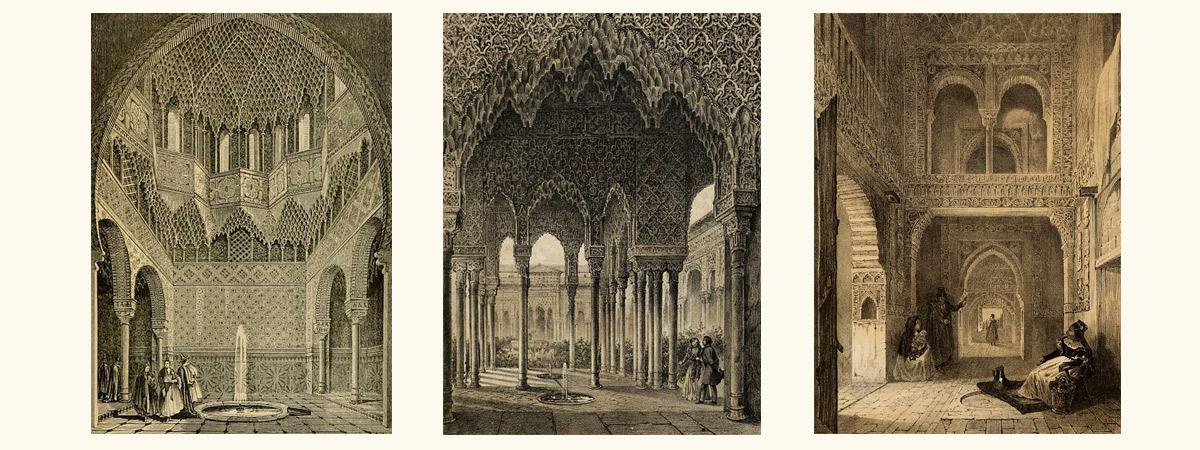

Rooms in the Alhambra. “Recuerdos y bellezas de España, bajo la real protección de la reina y el rey”. (Remembrances and beauties of Spain, under the royal protection of Queen and King). By J. Parcerisa. ©Wiki Commons

The Alhambra caused him an astonishing impression:“There we saw countless palaces, paved with blinding white marble; extremely beautiful gardens, adorned with lemon trees and myrtles, with ponds surrounded by marble surfaces in their sides; also four rooms full of weapons, spears, crossbows, swords, armours and arrows; the most sumptuous bedrooms and lounges; in every palace there were many basins of running water; one vaulted bath ̶ Oh, what a wonder! ̶ and at its outside the bedrooms; there were so many very tall marble columns that there exists nothing better; in the centre of one of its palaces, a huge marble basin stands on thirteen [sic] lions carved also in very white marble and from whose mouths water runs out like through a canal. There were many marble flagstones fifteen feet long and seven or eight wide, as well as many that were square, ten or eleven feet per side.

I do not think there is such a thing like this in Europe. It is all so superb, magnificent and beautifully built, with such a variety of materials, that one could believe one was in paradise. I simply cannot give a detailed account of it.”

When he is focused on describing the Alhambra, he cannot resist talking about the scenes related to the life inside the Nasrid palaces: “There was a beautiful marble basin in the bath where women and concubines bathed naked. The king, from a place with lattice truss in the upper part ̶ and that we saw ourselves ̶ beheld them and threw to the one he liked best an apple from above, as a sign that she had to sleep with him that night.”

The wealth of monuments captivates him: All the palaces and lounges, in the upper part, have ceilings and roofs so superb, made of gold, lapislazuli, ivory and cypress wood, in such a varied way, that it is not possible to describe or to write about it.

The water of the Alhambra speaks for itself in his account: “There is such a beauty in the palaces, with the water channels driven all over with such an artistry, that there is nothing more impressive. From an extremely high mountain, water is conducted through channels to be distributed all over the fortress.”

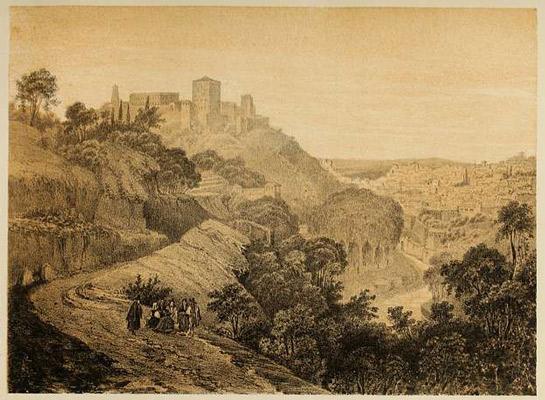

Views of the Alhambra from the Spring of the Avellano. “Recuerdos y bellezas de España, bajo la real protección de la reina y el rey” (Remembrances and beauties of Spain, under the royal protection of Queen and King). By J. Parcerisa. ©Wiki Commons

He devotes several passages to the grandeur of the city: “The city has seven hills with its corresponding slopes and valleys, all of them inhabited. The one that stands opposite the Alhambra, however, is the biggest. The Alhambra has towards the south, in the slope of its mountain, another city built eighty years earlier by the Saracens from Antequera, who took refuge in Granada when they escaped from that city after being conquered by Christians.

The plain is surrounded by many mountains. To the north is the Albayzín, another city outside the old walls of the authentic city of Granada. Its streets are so straight and narrow that houses normally touch each other in the upper part, and a donkey cannot normally allow another donkey to pass, unless it is in the most popular streets, where there is a width of maybe four or five cubits, so a horse can make way for another. Most of the Saracens’s houses are mainly so small ̶ with tiny rooms, dirty outside, and very clean inside ̶ that is hard to believe. Almost all of them have water pipes and cisterns. Water pipes and aqueducts use to be of two kinds: one that carried for clear drinking water, and another that removed sewage, manure, etc. Saracens understand this to perfection. Every street is provided with open channels for dirty waters, so that every house that does not have pipes due to the difficult terrain, can throw its filth by night into those channels. Sewers are scarce, but people are nevertheless very clean.

In Christian territory, a house occupies more space than three or four Saracen houses. In the inside, they are so intricate and jumbled that one might believe they were swallows’s nests. That is why it is said that in Granada there are more than one hundred thousand houses, as I believe it is. Their shops and houses are equipped with simple doors with locks and nails made of wood, as is customary in Egypt and Africa, since all Saracens share customs, rites, tools, dwellings, and other things.”

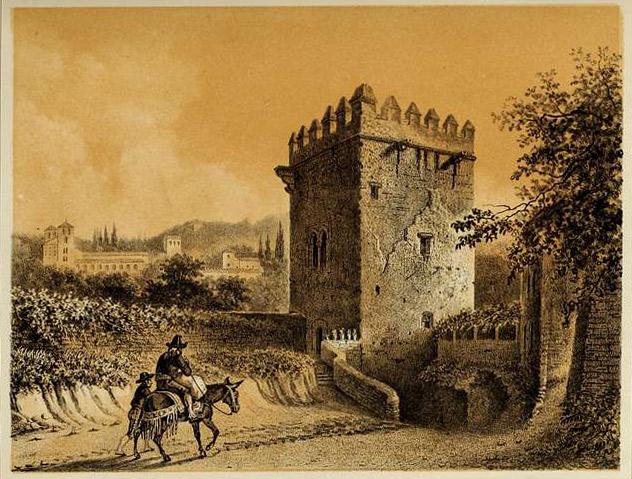

Tower of the Pointed Embattlements, Alhambra. “Recuerdos y bellezas de España, bajo la real protección de la reina y el rey” (Remembrances and beauties of Spain, under the royal protection of Queen and King)s. By J. Parcerisa.

About the Kingdom of Granada, he refers: The Kingdom of Granada, known among the ancients as Hispania Baetica, extends in the form of a semicircle, its diameter towards south being the sea. It is surrounded on all sides by very high mountains, and its interior is similarly mountainous. Its width, from its North to South, is a journey of three days, and its length maybe seven or eight. The most illustrious maritime cities it has are: Almería, which I mentioned before; Almuñécar (Almonikar), famous for sugar, where canes grow six or seven cubits long, and thick as a wrist; Velez-Malaga (Velismalica), an opulent city, with a magnificent castle; Málaga (Malica) a glorious seaport. The most famous Mediterranean cities are Baza (Bassa), Guadix, Granada, Loja, Alhama, Ronda and Marbella (Morbella). There is an uncountable number of castles and sites. It is not cultivated except where it can be irrigated. I think that the city of Granada is in the higher part of the kingdom, for at that time we did not see snow in any mountain but in the one called “la Sierra” (the Mountain) above the city of Granada.

There are also rivers with fresh and safe water filled with trout and other fishes that need cold spring water. The cities of the kingdom are generally located in the mountains and their slopes, so strong, whose their towers, defensive walls, barbicans, battlements are like no others. It is a very wealthy kingdom. It is bountiful in silk as there is no better in the world; it has also a lot of saffron, mostly in its lower part. Figs have a sugar-like taste, and they are not too big. It also produces olive oil, almonds, esparto, dyers’ cochineal, which costs one and a half ducats per two pounds, and many other things. All the rivers come from excellent and very fresh and sweet springs. In the summertime, water is never lacking due to the melting snow. And rain is not so frequent in any region of Spain ̶ given the mountains’ altitude, which is its cause as well the rise of vapours ̶ as it happens also in Metz and in Salzburg.”

On the vast cemetery located at that time by the Elvira Gate he says: “On 24 October, leaving in the morning by the Puerta de Elvira (Gate of Elvira), near our inn, we crossed that cemetery that is so large and is distributed in so many levels that it causes admiration. One of them was the old one, and it was forested with olive trees; the other has no trees. Those tombs belonging to rich people were surrounded, in a square shape, like the gardens, by walls of rich stone. We also went to the new cemetery, where we saw the burial of a man, and seven women dressed in white sitting by the grave, and the priest, looking towards the South, also sitting, singing and wailing loudly, while the women continually spread scented branches of myrtle on top of the grave. This cemetery is two times bigger than that of Nüremberg.”

Tower of San Lorenzo in the Albayzín, Granada. Drawing by Federico Ruiz del after the engraving by Edward Skill for the Spanish magazine El Museo Universal, 1860. 1860. ©Wiki Commons

On the mosque of the Albayzín, he points out: “Outside the walls of the great Granada, and close to the outskirts beyond the walls, there is another large city, named Albayzín, which has more than fourteen thousand houses that cannot be seen from the Alhambra. In this city, or rather, in this part of Granada, there is an extremely beautiful mosque, with eighty-six exempt columns, which is smaller, but much more beautiful than the main mosque in the city and has a very delightful garden forested with lemon trees.”

Some passages make remarks on some Muslim rites:“While meeting together in the mosques, they stand up, in an orderly way and barefoot, after having washed their feet, hands, eyes, anuses and testicles. At a signal from the priest, they bend, first tilting the head, hitting their breasts. Then they prostrate themselves on the ground and pray. They do this three times, and, believing that their sins have been absolved in this way, they return to their jobs.”

Moriscos in the Kingdom of Granada walking in the countryside with women and children. By Christoph Weiditz, 1529. ©Wiki Commons.

He gives precise details about the Muslim apparel: “I have not seen any man wearing tights excepting some pilgrims that wore them up to the knees, tied with knots in the back side, so as to be able to remove them easily in the time for prayer and the ablutions. Women, instead, wore all linen tights, loose and folded, which were knotted around the waist, at the height of the navel, like the monks. Over the tights, they wear a long linen shirt and covering it all a wool or silk tunic, depending on what they can afford. When they go out, they are covered by pure white cloth in linen, cotton, or silk. They cover their faces and heads in a way that only their eyes are shown.”

Finally, the description of a military game he attended as a guest of the Count of Tendilla is thorough: “On 26 October, Saint Simon and Saint Jude’s Vigil Sunday, the generous Count of Tendilla organized a gathering in our honour of around a hundred of his most skilled gentlemen, who had to play a military-style game in the esplanade of the castle of the Alhambra, one hundred thirty pitches long. Divided into two camps, they attacked one another with long and sharp canes, like spears; others, pretending to flee while protecting their backs with shields and bucklers, attacked in the same way their opponents, riders on their horses so rapid and agile in all their movement that there is no equal. It is a rather dangerous game, but by practicing in that fictitious struggle, they would be fearless of the spears in true war. Then, with shorter canes, with the horse at full speed, they posed as if they shot their arrows with bows or springs. I have never seen such a superb spectacle.”