Granadan by adoption, Ibn Jubair was a 12th century traveller and author whose work was paramount for the knowledge of the Mediterranean area under Muslim rule. He initiated a new form of travel literature: the rihla.

“It all started with an absurd story and a cup of wine…” according to chronicler Ibn Raqiq.

The compelling adventure along the Mediterranean Sea and the East by Ibn Jubair, one of the most illustrious Andalusi travellers, might have had its origins in a singular challenge that occurred in the year 1183, in the palace of Granada’s governor Abu Said Osman, son of the Almohad caliph Abd al-Mu’min. Ibn Jubair was at the time secretary to this Berber prince, who forced him, while dictating him a letter, to drink seven cups of the forbidden liquid in return for seven cups filled with dinars.

In order to redeem his guilt, and with the gold coins received in exchange, the pious secretary decided to comply with the obligation imposed on wealthy Muslims and undertake his pilgrimage to Mecca.

Whatever were the true motives of Ibn Jubair’s journey, which lasted two long years, held in its time a considerable resonance. The account of his tribulations throughout the East was the cornerstone of a new literary genre, the rihla, the travel narrative. So much so that in subsequent centuries, his emulators were countless and, including even plagiarists. The famous Tangerine Ibn Battuta −and many others− reused entire paragraphs of Ibn Jubair’s rihla, taking up, to give up just an example, descriptions of monuments that did not even exist anymore when they travelled around the same latitudes’ centuries later.

What could have been the reasons that pushed so many people from al-Andalus and the Maghreb to undertake the mythic and risky journey to those faraway lands, and particularly for affluent people like our learned one, who had received the traditional education for Andalusi secretaries, that is to say, trained in religious sciences and literature?

In the first place, faith was: “Pilgrimage rites are something sublime for Muslims”, as the author narrates, describing in great detail the places and moments of his stay in Mecca. As an added asset, the hard journey was also rewarded by the pride and prestige of obtaining wisdom from the Eastern masters, carrying the title of hajj (the accreditation of having made the pilgrimage) and, in his case, the iyaza (licence to teach). Could it not be added to such a persona like Ibn Jubair −native to Valencia and descendant of an Arab lineage, the Kinana, from the region of Mecca− a desire to search for his roots, or just the fascination for the world of the desert and the caravans, so clearly present in Andalusi poetry? Or was it perhaps just a simple desire for adventure?

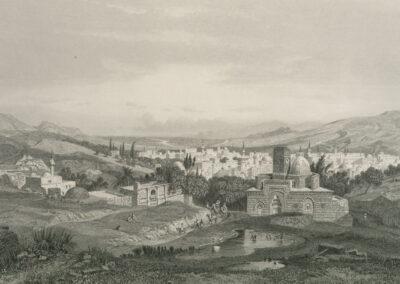

Ibn Jubair was 38 years old when he left Granada on the 19th of the month of sawwal in the year 578 of the Hegira calendar (5 February 1183). He travelled to Ceuta, via Tarifa, to be taken on board a Genoese boat going through Sardinia, Sicily and Crete. He stopped at Cairo to visit the tombs of the Prophet’s companions, imams and ascetics. He journeyed up the Nile Valley on camel-back until he reached Aydab, crossing from there the Red Sea on board a frail boat to get to Jeddah. He accomplishes his goal in August that same year, and he arrives to Mecca, where he was to remain almost nine months. His way back started by joining a huge caravan of pilgrims that stopped at Medina, the Prophet’s city-shelter. He travels across the deserts of Hejaz and the Najd towards Baghdad. In the Abbasid capital, he lauds the “natural goodness of its waters and air”, but he regrets that its people are exceedingly arrogant. He starts his journey travelling through the fertile lands of Mesopotamia until Syria. He was dazzled by Damascus, where he stayed for two months: “It is the Paradise of the East, a place where beauty rises elegant and radiant”. He heads towards the port of Saint John of Acre (‘Akka), occupied by crusaders, to sail westward. He starts a difficult two-month voyage, with adverse winds, that ends up in a wreck in the Strait of Messina, in Sicily. He waited three and a half months for the arrival of favourable winds to return to his land of al-Andalus. He finally disembarked in Cartagena, and on 25 April 1185 arrived at his Granadan home.

Ibn Jubair offers us a story in a style often concise and with some pompous touches, interspersed with interjections and poetic verses, an evocative and colourful picture of the lands he was visiting, with landscapes, cities, villages and markets rendered in astounding detail, reconstituting the human mosaic of these Eastern lands. The detailed descriptions of the mosques, tombs and monuments he visited comprise a great source of reliable information for archaeologists and art historians. His rambling journey not only keeps the reader on tenterhooks; it also attests the tense security situations on these land and sea routes, as well as the defencelessness of travellers before all kind of pirates: greedy customs officers in Alexandria, corrupt religious and political authorities in the holy places of Islam (Mecca and Medina), unscrupulous merchants and sailors from all corners of the globe, Kurdish, Arab or Sudanese tribes ready to assault the caravans of pilgrims and seize their goods.

Ibn Jubair’s epic is hence one of the most valuable accounts of how the Mediterranean region was at the end of 12th century, after having just experienced great changes due to the advance of Christian armies (the Syria and Palestine crusades, the Normans in Sicily, the fall of the Fatimid empire and the accession to the throne in Egypt of Salah ad-Din (Saladin), the paladin of Sunni Islam and the wars against the Franks.

Ibn Jubair tells us about the complex relationships between two worlds −the Islamic and the Christian− which watch each other out of the corner of the eye, face themselves, do business and live together, all simultaneously. He talks to us about the Genoese boats that take Muslim pilgrims to their holy places, about the prosperous Christian people in the land of Islam and vice versa. By means of his intense experience, he plunges us into religious problematics among the Umma, the vast community of believers. He introduces us to the religious sentiment of his time, during his pilgrimage through those lands of prophets, saints and great preachers and ascetics.

Trusting in the redemptive mission of the Almohads −who later on were to rule al-Andalus− this man of great learning, formed in the purest academicism of the al-Andalus Maliki school, does not exclude, however, the most unorthodox or popular manifestations of faith −and hence he visits the saint’s tombs and also attends emotional mystic sessions. This personality, not exempt from contradictions, is mirrored upon his return to Granada, where he enjoys great moral authority, and he asserts himself as both master of the hadith (the Prophets’ Tradition) and of Sufism. As proof of his modesty and humility (for example, he does not use the first person in his accounts) he led a peaceful and discreet existence, away from public life. Four years later, when Saladin conquered Jerusalem, he returned to the Orient, but there is no account of this journey, which also lasted two yearsHe was 72 years old when he undertook his last journey, passing by Mecca, Jerusalem and Egypt. He died in Alexandria on September 29, 1217.

The other great traveller, Ibn Battuta, wrote of him:

“He was a brilliant man of letters, a splendid poet and virtuous Sunni, and honest in his work, who had an excellent character, gracious manners and an elegant calligraphy.”