Dar al-Horra, the story of a house of noble lineage

The property is located in Granada’s historic district of the Albaicín, and it is an exquisite example of the domestic architecture of Al-Andalus dating from the Nasrid period, the last stage of the Hispano-Muslim culture.

The palace of Dar al-Horra was built in the 11th century by the Zirid taifa king Badis, probably on the same foundations of the ancient fortress (Qasaba Qadima), whose walls enclosed the property. The destruction of the military fortress was complete, and its plot was then occupied until the 15th century by a great orchard known as “Huerta de la Alcazaba Antigua”, (the orchard of the ancient fortress), [al-yanna al-‘ulya min al-Qaşaba al-Qadima].

The house, as we know it today, was part of a great extension that produced different agricultural products, mostly vegetables and fruit trees, thanks to the water that came from the nearby Aljibe del Rey (Cistern of the King). It has an orchard, cut through by the ditch that watered it, from which the remains of its canal have survived.

The gardenwas one of the most important spaces in the residences of Al-Andalus. It was a place for enjoyment and rest, but it also helped to supply fruits, vegetables and plants for diverse use (culinary, medicinal and ornamental). Many of them are still the main features in Andalusian gardens today, including myrtle, jasmine or the orange tree, whose blossom have an intense aroma.

In the picture on the right, we can see a prototype of an orchard-garden of Al-Andalus. Plants, both aromatic and ornamental, medicinal, those used for cooking, as well as fruit trees were grown in this Nasrid palace. Here, the garden was watered thanks to the channel (in the foreground) that was fed by the nearby Aljibe del Rey and by a well that can be seen in the background.

The property is located in the highest part of the Albaicín’s hill, in an area that provides a 360-degree view, and hence makes visible all the roads that reached the city. From north and the city of Guadix, Wadi As, considered to mark the beginning of the Nasrid Kingdom’s area, was also the road that came from the famous port of Almería, and from south the road connected the city with the coasts of Granada. Today, for instance, we can see from its lookout tower the castle of Moclín, which was an important border-crossing point, given the defensive needs of the Kingdom of Granada after the advance of the Christian armies.

King Muhammad X sold the house to his daughter Aixa, wife-to-be of king Muley Hacén. When Muley Hacén, Boabdil’s father, repudiated Aixa to get married to the Christian slave Isabel de Solís –who converted into Islam under the name of Soraya– Aixa left the Alhambra palace and moved here, from where she had before her eyes the whole Alhambra, its towers and palaces. Aixa’s house became a lookout from where she controlled the movements that took place in the court, interpreting them as signals: if torches were lit all night long, it could be surmised that the long-lasting meetings corresponded to the magnitude of the problem. This aroused intrigues in the courts of both of the palaces, which were opposed in the most literal sense.

Tras la Conquista de Granada, la finca fue adquirida por Hernando de Zafra, secretario de la reina Isabel la Católica, quien a principios del siglo XVI funda en esta mansión nazarí un convento de religiosas franciscanas clarisas, que llevó el nombre de Santa Isabel la Real en honor suyo.

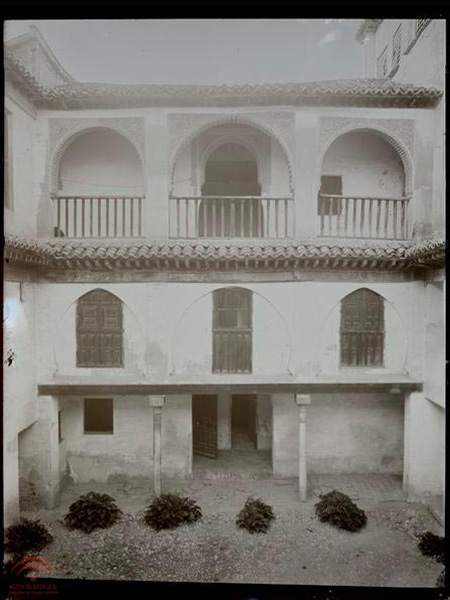

The porch of the present northern wing

The architecture of this site is purely Nasrid. Privacy in domestic spaces was ensured by the lattices of the windows and lookouts, which allowed one to see without being seen.

Barely 12 years had passed by since the Conquest of Granada when Queen Isabel built the first cloistered convent in Granada which, according to the first royal stamp of approval to set up the convent, was to be built in the Alhambra. In the year 1504 a new royal approval had to be signed to finally locate it in the place where it is nowadays. The reasons behind the decision of locating the convent in a property owned by Hernando de Zafra remain unknown.

After the “Desarmotización de Mendizábal” (Mendizabal Disentailment) in 1835, the convent was the only one that was not affected, and its patrimony was even increased with the goods that other convents transferred to it once the confiscation took effect.

The part belonging to the northern edge of the convent was preserved practically intact, but later on, a great part of the palace was demolished to get it high enough to house the convent chapel. Next, two lateral floors were erected in the east and west, and on the other sides, mezzanine floors were built. For the construction of one of them, the portico and the northern lower hall had to be demolished, while some horseshoe blind arches, with scarce historic rigor, were recreated (fig 1). In the same way, the original dimensions of the big lounges were reduced in order to produce a greater number of rooms of smaller sizes.

(Fig. 1). Portico and lower hall of the northern wing before its intervention. ©Archivo del Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife.

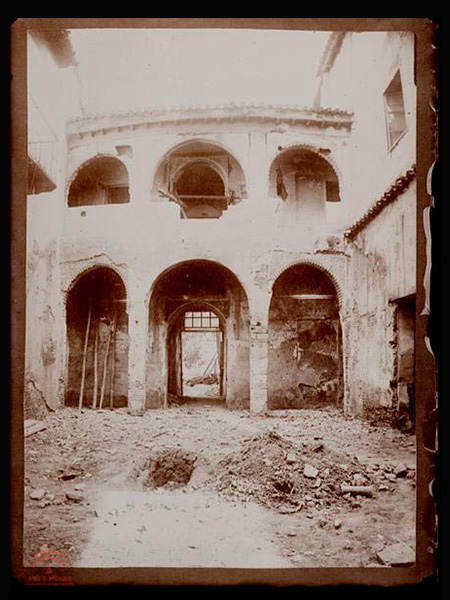

(fig. 3). View of the southern portico before its intervention. ©Archivo del Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife.

In 1931, the architect-curator of the Alhambra, Leopoldo Torres-Balbás started the restoration works of the house, once the ensemble was purchased by the state, trying to approach as much as possible its original design.

Image number 2 shows the state in which the ensemble was found. ASome adjoining buildings had to be purchased later on, since they were an elemental part of the original house. We are referring here to the western part, where a series of modules totally in ruins were annexed; it was here were Torres-Balbás found the original access from the street to the house. His great knowledge of restoration of Arab architecture allowed him to identify in this space the existence of a spacious room dating from the 16th century.

The proposal that he made to restore Dar al-Horra was divided into two main phases:

In the first one, the space that the house occupied regarding the convent was defined, and an access from the street was opened, which made it necessary to demolish works with clearly modern features. Then focusing on the Nasrid part, he went on to clean and identify the walls to determine those parts that were the oldest.

The scientific techniques used show the modernity of the methods he employed. In the same way, the excavation of the whole perimeter purchased by the state was made. As a result of this intervention, a vast walled enclosure of some 5 meters square was discovered in the western half of the yard, as well as the northern corridor which connected with the primitive pool, which, according to Antonio Orihuela (CSIC) was probably the water cistern.

In the second phase, which in all likelihood may be attributed to the architect-curator of the Alhambra, a full refurbishment of the western part was planned, so as to leave the house-palace totally exempt. Such a work implied its complete demolition, except for a building that included a 16th-century framework.

In the plans that were made to go ahead with the intervention of this second phase, we can see the chapel structure in the southern hall.

(fig. 2). Northern façade of the yard. ©Archivo del Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife.

The architect who succeeded Torres-Balbás in the restoration of Dar al-Horra was Francisco Prieto-Moreno, who after the interruption of the works due to the Civil War, chose to use the money assigned for urgent works to start the works again in 1941. The main work took place in the western garden, where the access from the street is. Also, the groundskeeper’s home was built in the northern part of the garden. This entailed demolishing the northern side of the building that was identified by Torres-Balbás, which included an octagonal structure from the 16th century.

Subsequent projects of restoration were focused inside the house, such as the flooring of the southern hall, or the relocation and the re-dimensioning of the pond, for which the Casa de Zafra model was followed. In the years 1959, 1965, 1968 and 1979, Gómez-Moreno undertook different projects of conservation and repair, using a mortar bed of concrete for the coating of facings.

Restoration works are continuing to be carried out, within the wide project of restoration led by the Andalusian Government (Junta de Andalucía), since the national Ministry of Culture transferred the monument to it in 1984.

Partial view of the yard of the Palace of Dar al-Horra

Currently, the palace of Dar al-Horra houses an exhibition organized by the Foundation El legado andalusí under the title The Science in al-Andalus. It introduces the scientific progress which, thanks to Arab scholars was transferred from ancient cultures to Medieval Europe thanks to a joint effort undertaken by the scholars of al-Andalus.

Al-Andalus represented a great center for the dissemination of knowledge, and was homeland to the most important achievements in medical, astronomical, geographic, or agricultural matters, in short, to all the disciplines from which modern science has nourished thereafter. Muslims, Jews and Christians and many people devoted to knowledge, worked on a scientific corpus on which they applied all their research, broadened and glossed for dissemination throughout the known world at that time.

By Ana M. Carreño Leyva. Fundación Pública Andaluza El legado andalusí

Bibliography:

TORRES-BALBÁS, LEOPOLDO. “Proyecto de obras de reparación del Palacio de Dar al-Horra”. Memoria 1930. P 1-6 A.G.A, 13178-10

PRIETO-MORENO PARDO, Francisco. “Proyecto de restauración del Palacio del Dar al-Horra”, 1942. Ministerio de Cultura, Archivo Central, c.71.091

ORIHUELA UZAL, Antonio. Casas y Palacios Nazaríes. Siglos XIII –XV. El legado andalusí. 1996.