Beyond the pillars of Hercules

Part II

The Arabs knew the Canary Islands through Ptolemy, and called them Jaza’ir al-Khalidat, “The Eternal Isles,” presumably a version of the Greek name. Some sources speak of these islands as if they were legendary, telling us for example that on each of the six islands ̶ there are in fact seven ̶ there was a bronze statue, like the one in Cádiz, warning voyagers to turn back. But al-Idrisi, the famous 12th-century geographer who wrote at the court of King Roger of Sicily, tells of an attempted expedition to the Canaries in the late 12th-century, during the reign of the Almoravid emir Yusuf ibn Tashafin. The admiral in charge of the expedition died just as it was about to set out, so the venture came to nothing. Al-ldrisi says the admiral’s curiosity was aroused by smoke rising from the sea in the west, probably the result of volcanic activity.

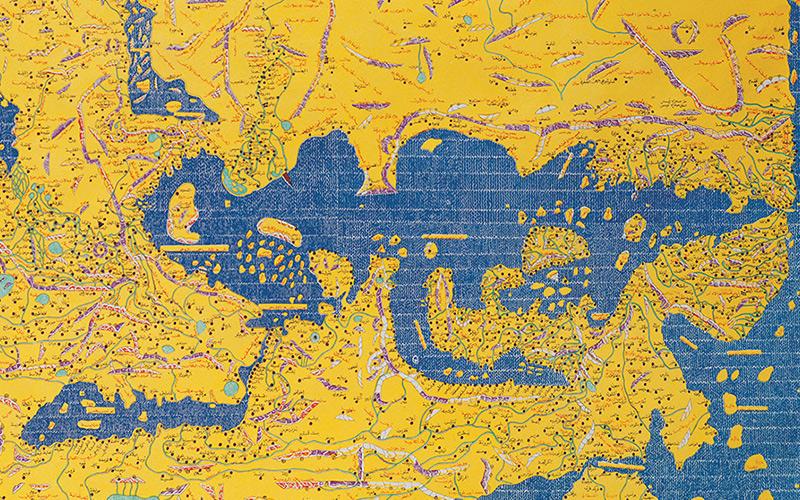

Map by al-Idrisi as he envisioned the Mediterrranean area, with the north and south positions upside down.

Al-Idrisi nos habla de otras islas más del oeste Atlántico:

“Sawa se sitúa “cerca del Mar de las Tinieblas”. Alexander the Great spent the night there just before entering the western darkness. The inhabitants threw stones at the travellers and hurt several of Alexander’s companions.

The inhabitants of the island of al-Su’ali are shaped like women and their canine teeth protrude. Their eyes flash like lightning and their thighs are like logs. They fight against the monsters of the sea. Men and women are not sexually differentiated, and the men have no beards. They dress in the leaves of trees.

The island of Hasran is crowned by a large, high mountain. A small fresh-water river runs down from the foot of the mountain, where the inhabitants live. They are short, brown people with broad faces and big ears. The men’s beards reach their ankles. They eat grass and other plants.

Al-Ghawr is long and broad. Many herbs and plants grow on the island. There are many rivers and pools, and thickets where donkeys and long-horned cattle take refuge.

The island of Qalhan is inhabited by “animal-headed people” ̶ who might well be seals ̶ who swim in the sea to catch their food. Then there is the Island of the Two Brothers, Shirham and Shiram, which could be the two small islands off Lanzarote, Alegranza and La Graciosa, or indeed, any two prominent rocks off their coasts. God changed them to stone for practicing piracy, the legend has it. This island is near Asfi (Safi, Morocco) and on a clear day smoke can be seen rising from it. It was this smoke that led to the abortive expedition by Yusuf ibn Tashafin’s admiral.

Al-Mustashkin is said to be inhabited. It has mountains, rivers, fruit trees, cultivated fields and a town, with high walls. . It used to be a dragon in the area, and the people were forced to feed it with bulls, donkeys or even humans, according to the legend; when Alexander arrived, the people complained to him of the dragon’s depredations. Alexander fed the creature an explosive mixture and blew it to pieces.

Some of the names of these islands make sense in Arabic, others do not. Sawa has no meaning. Al-Su’ali is a word that refers to a kind of female demon or vampire; judging by al-Idrisi’s description of the female inhabitants of the island, it is apt. Hasran means “regretful” ̶ Island of Regret? ̶ – but if the variant Khusran is chosen, it means “loss”, perhaps Island of Loss, or Lost Island. But if the word is Arabic, one would expect it to be preceded by the definite article ‘al’.

Al-Ghawr makes sense; it means a depression surrounded by higher land and occurs elsewhere in the Arab world as a place name. Al-mustashkin is probably a corruption of al-mushtakin, meaning “the complainers”, appropriate enough for a population in thrall to a dragon. This story of Alexander and the dragon echoes the Eleventh Labour of Hercules, the Golden Apples of the Hesperides, guarded by the dragon Ladon.

In the Arabic-speaking world, popular legend transferred a number of the heroic deeds of Hercules to Alexander, including the building of a land-bridge across the Pillars of Hercules. Some Greek mythographers thought the Islands of the Hesperides lay off the coast of North Africa, and we have already seen how al-Idrisi associates Alexander with two of the Atlantic islands.

Al-Idrisi gives the names of thirteen islands in the western Atlantic; the number fourteen was visited by the Mugharrirunand is nameless. This unnamed island, together with Masfahan, Laghus, The Two Brothers and possibly Sawa, are almost certainly islands in the Canary group. Laqa might be Madeira, and Sheep Island and Raqa part of the Azores group. Where al-Su’ali, Hasran, al-Ghawr, Qalhan and al-Mustashkin lay is anybody’s guess. Al-Su’ali and al-Mustashkin both sound completely legendary, but there is nothing legendary about Hasran and Qalhan, which sound as if they might belong together. Since the only inhabited islands in the western Atlantic just before the coming of the Europeans were the Canaries, Hasran may belong to that group —unless, of course, it is to be sought in the Caribbean!

A last island in the western Atlantic is Laqa. Al-Idrisi says aloe trees grow there, but their wood has no scent. As soon as they are taken away, however, the scent becomes perceptible. The wood is deep black, and merchants come to the island to harvest it and then sell it to the kings of the farthest West. The island is said to have been inhabited in the past, but it fell to ruin and serpents infested the land. For this reason, no one can land there. Could Laqa be Madeira? Madeira was heavily wooded when first settled in the 15th century, hence its name. The settlers quickly burned down all the forests, so it is now hard to know for certain, but some sort of scented wood may have once grown there.

Madeira was much appreciated for its timber, given the abundance of woods in the island. Original rain forest can still be found here as in the rest of Micronesian islands: Madeira, the Azores, Canary, Cape Verde and the Wild Island.

Here is another tantalizing reference to early Atlantic voyages, this time from al-Mas’udi. The account must date from before AD 942, the date al-Mas’udi completed the book from which it is taken:

“It is a generally accepted opinion that this sea ̶ the Atlantic ̶ is the source of all the other seas. They tell marvellous stories of it, which we have related in our work entitled ‘The Historical Annals’, where we speak of what was seen there by men who entered it at the risk of their lives and from which some have returned safe and sound. Thus, a man from Córdoba named Khashkhash got together several young men from the same city, and they set sail on the ocean in ships they had fitted out. After a rather long absence, they returned with rich booty. This story is famous, and well known to all Spaniards”.

The Historical Annals, which presumably gave a much more detailed account of this and other voyages, is lost. That the story was preserved at all is probably due to the rarity of such voyages. On the other hand, this passage shows that Atlantic voyages were made, and remembered.

In what direction did Khashkhash sail? If he went north, he may well have plundered the coasts of Portugal, France or even England. But the story occurs in the context of a discussion of the All-Encompassing Sea, not the coasts of northern Europe, which were relatively well known to the Arab geographers. The context implies that Khashkhash sailed west. If so, the nearest place that could offer rich booty was the Caribbean.

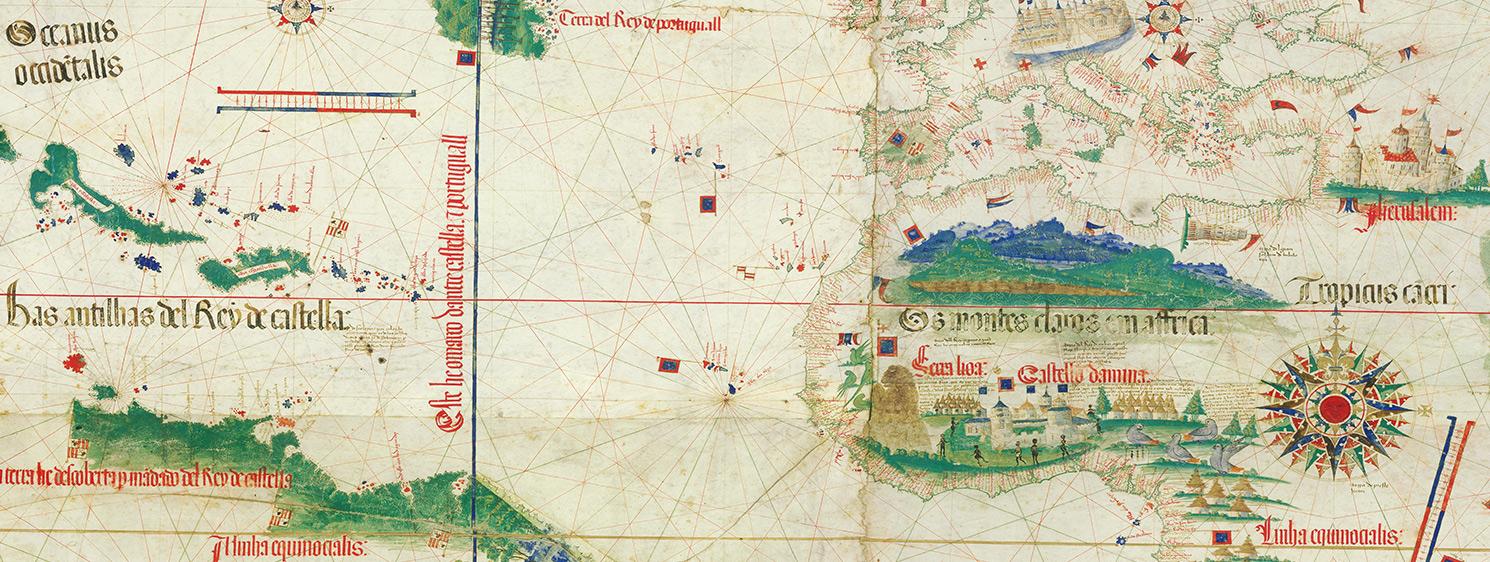

Planisphere of Cantino, made in Portugal in 1502, which is preserved in the Estense Library of Modena. Italy.

These imaginary islands were marked on 14th-century charts, along with others.

The Antilles and Brazil, for so long legendary, continue today as the names of real places.

Men were still seeking St. Brendan’s Isle as late as the 18th century; Ilha Verde, the Green Isle, did not finally disappear from mariner’s charts until the middle of the 19th century. Throughout the Middle Ages, stories of islands to the west kept interest in the far reaches of the Atlantic alive, , and when real islands began to be discovered in the 14th century, the legends took on new life. Indeed, if the Islands of the Blessed really existed, why shouldn’t the Antilles? In the 15th century, as the Azores, Madeira, the Canaries, and the Cape Verde Islands were gradually colonized and brought under sugar cultivation, the search became more intense. Genoese bankers were willing to finance sugar production; the search for free land ̶ unencumbered by tenants who enjoyed hereditary rights and paid fixed rents in inflationary times ̶ was seen as an escape from economic depression?

And who knew what lay beyond the Canaries, or the Azores? After all, al-Idrisi, who repeatedly says that nothing lies beyond the Eternal Isles, splendidly contradicts himself by telling us in another passage, quoting no less an authority than Ptolemy himself: “There are 27,000 islands in this sea, some inhabited, others not; we have mentioned only those closest to the mainland, and which are inhabited. As for the others, there is no need to mention them here.”

Volcano. Azores Islands.

These Atlantic islands have many common features, including the fauna and flora and its volcanic nature.

VolcanoTeide, in Tenerife. Canary Islands.

This is the background against which Columbus’ voyages were made. He had taken part in the expeditions sent along the African coast by Prince Henry the Navigator. He knew the Atlantic islands well; his wife was the daughter of Bartolomeo Perestrello, one of the early settlers on Madeira. Her sister was married to Pedro Correa, of the same island, who found a piece of worked wood cast up on the beach that he believed had drifted east from unknown western lands. Columbus son Hernando, writing in 1537, shows very well the grip these islands had on his father’s mind, after first describing his father’s reading in ancient and medieval sources and Paolo Toscanelli’s letter on the possibility of reaching Asia by sailing west:

“The third and last thing that led the Admiral to discover the Indies was the hope he entertained, before reaching them, of finding some island or land of great utility, from which he could continue his main search. He was confirmed in this hope by reading the books of many wise men and philosophers who said, as a thing not admitting doubt, that the greater part of our globe is dry land, because the area covered by land is greater than that covered by water. This being so, he argued that between the coast of Spain and the borders of India then known, there would be many large islands, as experience has shown. He believed this the more readily because of certain fables and stories which he heard told by various people and mariners who traded in the islands and the seas west of the Azores and Madeira. These were stories which fitted in with his own opinions, and he remembered them. He never tired of telling them, to satisfy the curiosity of those who enjoy such curiosities”.

Paul Lunde.

Historian and Arabist

Text published thanks to the ARAMCOWORLD’s collaboration. 1992, Mayo-Junio.