Baeza, oblivion and presence

The Route of the Nasrids is home not only to genuine art relics from the Al-Andalus period; cities like Baeza are the quintessence of the Spanish Renaissance

I reached Baeza after having read a historical account as strange as the pages of the Da Vinci code, but a real one. It was written in the 18th century by the Jesuit Andrés Marcos Burriel and it reads thus:

“At the head of all the laymen came the clergy, composed of Bishops, […]. They were leading the triumphal cart as a token of respect, which was arrayed sparing no with expense, and giving as much as the idea of magnificence could ask. The Queen of Heavens was accompanied by the queen of Seville Doña Juana, and both majesties were followed by princes Don Alonso the Wise, Don Fadrique, Don Enrique, Don Sancho, Don Manuel, sons of the king: the prince Don Alonso de Molina ̶ his brother ̶, prince Don Pedro son of the king of Portugal, prince Don Alonso, son of the King of Aragon James the Conqueror, Hubertus cousin of pope Innocence IV, without forgetting here the one who was born prince and heir to the throne, and to whom all pre-eminences were due thanks to the fortunate exchange made for his succession in the true faith by his father Don Fernando Abdelmón, son of the King of Baeza”

He was narrating the entrance in Seville in the year 1248 of King Ferdinand III and, in it, we can see how Don Fernando Abdelmón occupied a leading place. To him the monarch of Castile and León gave properties in the Santiago quarter, bordering the Morería (Moorish quarter) of the Granadans and the bread market and, also, olive oil mills in Marchenilla, a place close to Alcalá de Guadaira, where a castle with the same name still stands. This is how the fruits of the Hill of Úbeda got together symbolically with those from the Sevillian countryside as well as its golden juice.

I arrived in Baeza when in the fight for the sun in the plaza of Santa María the cathedral was easily defeating the Seminary, and in the streets, not a soul was there, nor in the hotel where, apparently, they were not expecting me until the following day. So, retracing my steps, I got deliberately lost in the streets until I found by chance the Ruins of the Convent of Saint Francisco, as they are known, which in fact they are no longer so because, although Andres de Vandelvira chartered its design in the 16th century, it was not finished until around fifty years ago. The new architect did not want to find fault in his predecessor’ labour and he only “drew” with steel the curves of the vaults.

Convent of de San Francisco

From there I went up to the Gate of Úbeda, which surely would be from where Ferdinand III, Don Abdelmón and his father departed for conquest of that city, taking probably their same path, after drawing it in my notebook while drinking a beer, I found in the Paseo de Antonio Machado (Promenade of Antonio Machado) his same loneliness.

Through the fields of my land

Embroidered with dusty olive-trees

I am walking alone

Sad, tired, pensive, and old.

Panoramic view of the countryside of Baeza.

On the vast panorama of the horizon, gaps of sun and shadows alternated, leaving behind dispersed clouds as a presage of others arising. Much must have rained here from Don Abdelmón to Antonio Machado, much water has passed under bridges, but it keeps on coming in the same way. The poet maybe heard the popular saying: “When the Aznaitín puts on the montera, it rains, although God does not want it to”, and it might have been right here where he thought to write:

Sun over the mounts of Baeza.

Mágina and its black cloud.

The storm sharpens

Its knife in the Aznaitín mount

With the green and silver sea of olive trees curled by the wind’s knife I returned to enter Baeza again, and again along the streets close to the church of Santa María, passing the last remains of the church of San Juan Bautista, allowing the stone to saturate my sight over and over, broken only by some cypress popping up from a wall like the weapon of an invisible lancer guarding the church of Santa Cruz. The temple is secluded and austere. Nothing disturbs its pristine raw naked beauty; the Romanesque tympanums of the two doors are kind of funnels that lead to the naves on its interior where a horseshoe arch, which might be Mozarabic, is a witness of those times which, as those of Don Abdelamón, have disappeared from memory. Almost alongside, the contrast. The palace of Jabalquinto rises like a wall of lace, as if it was the ceremonial armour of this city, inviting you to enter its courtyard to be astonished before its staircase, two centuries younger than the façade but showing the same horror of emptiness.

Palace of Jabalquinto. Headquarters of the International University.

And the University. For everyone who arrives today, its long story is overshadowed by the huge figure of a dishevelled teacher of French: the figure of Don Antonio Machado who crossed here its yard a thousand times, who gave his lessons and got out to walk “with his solitudes”, always with Soria in his mind, because it was there that Leonor had died.

The cathedral stands in the same place as did the mosque, even though this was also a cathedral by the mid-12th century when Alphonso VII conquered the city in the agonizing years of the Almoravids. From that time only the beautiful lobes of the arch of Puerta de la Luna (Gate of the Moon) at the foot of its nave remains. Only that.

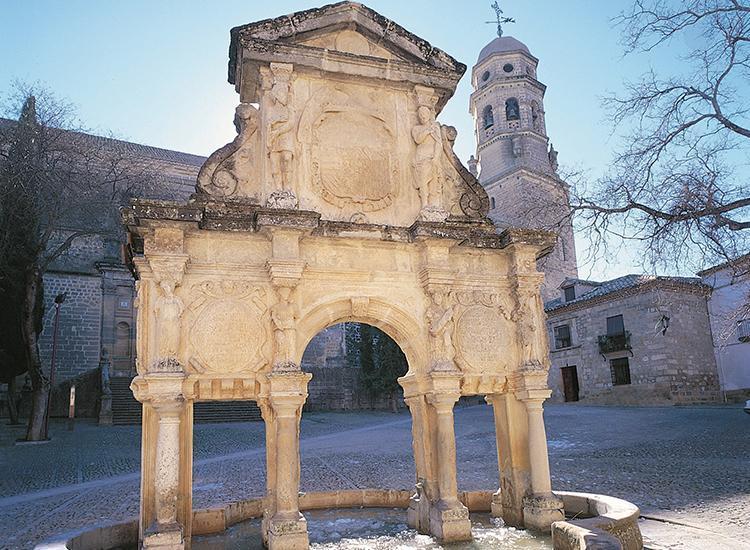

Next to the episcopal see, the Casas Consistoriales Altas (High Town Halls) plant in stone their brand-new Gothic style that already links up the architectural styles brought by the Emperor, also incorporating the Neoclassic canons of the palace of a family from Baeza, the Rubín de Cevallos. On the opposite pavement the sun dyes the ashlars of the old seminary of San Felipe Neri a chalky sand colour. But eventually, what dominates here is the shadow of the cathedral; below it the fountain of Santa María keeps on singing —indifferent— the chant of its water.

The Fountain of Santa María is a triumphal arch that heralds from the 16th century the wealth shared out to the maze of orchards.

Baeza has many fountains: the one of Santa Maria, the one of La Estrella, queen of the gardens, whose star, on the peak of an obelisk commemorates “la Gloriosa” (The Glorious), the revolution of 1868 that forced Elisabeth II into exile and gave way to the First Spanish Republic, or that fountain of the Puerta de Toledo (Gate of Toledo) whose origins date back to the 17th century. The oldest one is the Fuente del Arca and what pulls them all to the edge are the lions and bulls in the Fuente de los Leones (Fountain of Lions) in the Pópulo Square, for they and the coarse Diana that presides over it arrived here after being inhabiting in the Iberian settlement of Cástulo.

Towards it I have set my steps but going out of my way to first look for the remains of another building that was a temple, that of San Pedro, maybe as old as that of Santa Cruz, disentailed in the 19th century, and today just a romantic ruin that serves as a vertex for the sides of the angle that opens from the Paseo de las Atarazanas onto the Pópulo.

This fountain lies right in the middle of this ensemble, which consists of the wall with two gates where the gate of Jaén was, which Queen Elisabeth the Catholic commanded to destroy. One of the arches is named “of Villalar” because, apparently, it was raised to commemorate the battle in which the newcomer Charles V defeated the Comuneros, that is, the representatives of the towns. The winding life of these cities is a strange paradox, for it will be never known the real reason why what it was demolished by the grandmother was rebuilt to honour the grandson, or to bolster, eventually, those who should have obeyed that order.

Plaza del Pópulo with the Arch of Villalar and the Gate of Jaén.

Yet today the plaza is here, with the Antiguas Escribanías (old stone desks for public use) propped up against the wall in a strange way, if one does not know that a street altarpiece of the Virgen del Pópulo was there not much time ago, preserving the legend of this place being where the first mass was celebrated in the 13th century.

In front of the two gates stands the building of the Carnicerías (Abattoir) with its huge imperial coat of arms, heralding the importance of Baeza in the 16th century.

In direct line with the Paseo de la Constitución (Promenade of the Constitution), a hall of the 19th century, with a music kiosk, which was previously a market square and, surely, the site of the weekly souk much earlier, we can see the Balcón del Concejo (Balcony of the Town Hall), a preeminent place for the authorities to attended great bullfights and other celebrations. Behind, a kind of itinerant Triumph, for this was not its first location, and in the opposite sidewalk sits the Alhóndiga (place to accommodate merchants and their goods). In the background, the Plaza de España which was highlighted much earlier for the star in the fountain, and the Aliatares Tower, proud and serious, defender of a barbican that today is but the name of a street, and opposite of the street of the Hospital de la Purísima.

Town Hall’s façade of Baeza, Jaén.

The town hall reveals almost right next to it, the Plateresque style that frames its balconies and windows. Beyond, the hulk of the church of El Salvador returns us to the time that mixed Gothic and the canons of Al-Andalus, the Mudéjar, thanks to which Al-Andalus did not became archaeology. If for Metternich war was the continuation of politics under a different form, Mudejar did the same to allow Al-Andalus to be kept alive under other regalia.

Yet, Fernando Abdelmón did not return to Baeza, nor even to die as did Pablo Olavide. He is buried under the pavement of the cathedral of Seville.

Antonio Zoido.

Writer