Walks through Seville

O river of Seville, will that time never return, even if only in dreams?

Al- Kutandi. Poet from al-Andalus (12th century)

The array of sensations that the Andalusian capital evokes in the traveller is a privilege reserved for only a few cities in the world. As in times past, few are those who do not instantly succumb to its charms: to its welcoming southern atmosphere, the refinement of its art, architecture and urban design, the depth of its history and the subtle romantic air tinged with sensual exoticism. It is a fitting gateway for a route dedicated to Washington Irving, who once lived in the city and saw in it glimpses of One Thousand and One Nights.

The roots of Seville reach deep into a mythical haze some three thousand years ago, when, according to legend, it was founded by Hercules himself. Strategically located where the Guadalquivir River opens to the influence of the Atlantic Ocean, the city thrived in an ideal position for both land and sea trade. It began to flourish in the early centuries of the first millennium BC, as part of the Kingdom of Tartessos and within the sphere of Phoenician colonies. Later, the Carthaginian presence gave way to Roman rule. Hispalis, the ancient Seville, rose to prominence as one of the capitals of the prosperous province of Baetica, rivalling the nearby aristocratic city of Italica, the birthplace of emperors Trajan and Hadrian. During the Visigothic era, Seville maintained its importance and by the 6th century, it stood out as one of the most vibrant centres of learning in Europe.

Incorporated into Muslim rule in 712, Seville briefly served as the capital of the emerging state of al-Andalus before the seat of power moved to Córdoba. Ishbiliya—the Andalusi Seville—would go on to rival this other great city of the Guadalquivir, often rising in rebellion against its rulers. The disintegration of the Caliphate in the 11th century marked the beginning of a golden age for Ishbiliya under the Arab Abbadid dynasty, who established it as the court of the largest and most powerful of the Andalusi taifa kingdoms. Al-Mutadid and his son al-Mutamid—the celebrated poet-king—oversaw its peak, nurturing an extraordinary cultural and artistic flourishing that would leave a lasting legacy. By then, it was already the court where everything converged, a cosmopolitan emporium at the crossroads of seas and continents. The North African empires of the Almoravids and Almohads would further elevate the importance of Ishbiliya, shaping its final urban form. The Almoravids traced the vast perimeter of city walls that still define the historic centre today, while the Almohads established it as the capital of their Andalusi empire. By the 12th century, Seville ranked among the foremost cities of Europe. The brilliant Muslim chapter of Ishbiliya came to a close in 1248, when the city surrendered to Ferdinand III. With Seville, the entire Lower Guadalquivir region fell under Christian rule. Once again, the city became a princely seat, and its history and legend became forever entwined with the figure of King Peter I. In his Sevillian court, he forged a remarkable synthesis, embracing and preserving elements of Hispano-Islamic culture with notable harmony.

While serving as an outpost facing the last Muslim stronghold—Granada—Seville also became a gateway for commercial exchange with the Nasrids, following the very route traced by these pages. With the discovery of the Americas, the city reached its zenith, transforming into a new Babel where people from all over the world converged. These golden decades, even as they faded, gave way to the Romantic century and to the image of the traditional city that continues to enchant travellers with its customs and gentle charm. Writers, painters, illustrators and ordinary tourists alike were drawn to Seville from the early 19th century, seduced by the dreamlike allure of its myths—Don Juan, Figaro, Carmen—by its people and by the spell cast by its winding streets.

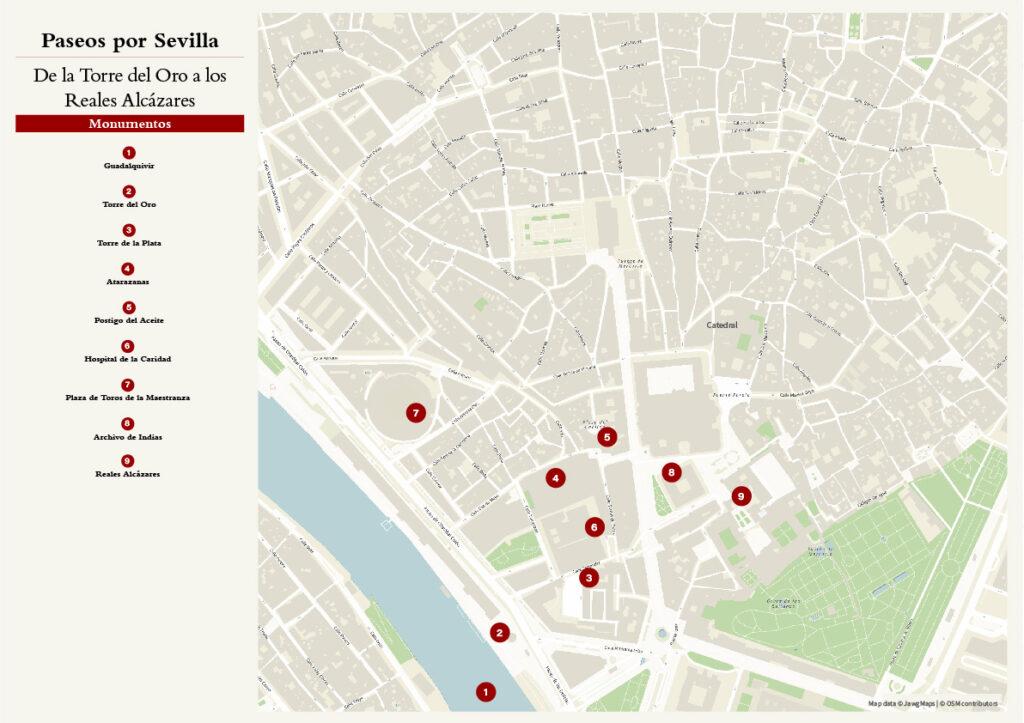

1. From Torre del Oro (Golden Tower) to the Alcazar.

The Great River—the Guadalquivir—forms the most open and expansive façade of the historic city centre and makes for a perfect starting point to explore Seville. From the very beginning of the walk, the legacy of al-Andalus is unmistakable: a subtle Oriental touch lingers in the air, woven into the city’s layout, its hidden corners and its monuments.

The impressive polygonal bastion of the Torre del Oro (Gold tower) rises prominently along Paseo de Colón, marking the site of Seville’s former port. Built by the Almohads around 1221, this stone tower—topped with a small turret of brick and decorative tiles—now houses a captivating Naval Museum. Inside, visitors can explore Seville’s long-standing relationship with the river and its maritime past. In its original context, the tower formed part of the defensive system of the Andalusi city. It was linked by walls and towers—including the Torre de la Plata (Silver tower), located on nearby Santander Street—to the city’s fortified walls and the powerful Alcazar complex. In these historic and lively old port districts—from the Torre del Oro to El Arenal—visitors will find numerous points of interest. Among them are the Atarazanas, a series of spacious vaulted halls originally used as royal shipyards and naval storehouses, likely dating back to the Almohad period and later rebuilt by King Alphonso X. Nearby, the visitor will come across the Postigo del Aceite, a surviving section of the old city wall and the striking tiled façade of the Hospital de la Caridad (Charity). This 17th-century Baroque building deserves special attention, not only for its architecture but also for the remarkable artworks it houses—including masterpieces by painters Murillo and Valdés Leal. Lining the edge of Paseo de Colón stand two iconic landmarks: the Teatro de la Maestranza, Sevilla’s premier music venue, and just a little further along, the city’s celebrated bullring, the Plaza de Toros de la Maestranza. Constructed from the 18th century onwards, the bullring is one of the most emblematic in Spain. Its tiered seating, open to visitors alongside a fascinating museum that explores the history and traditions of bullfighting, has long been — and still remains — an essential stop for travellers, irresistibly drawn by the enduring allure of the spectacle. At the southern edge of the old town, near the river, lies the monumental heart of Seville, where some of the city’s most iconic landmarks stand side by side. Here, the Archivo de Indias, a sober Herrerian-style building from the late 16th century, houses the most important documents related to Spanish America. Nearby are El Triunfo square, the Royal Alcazar and the Cathedral with its famous bell tower, the Giralda. Together, the Archivo de Indias, the Royal Alcazar and the Cathedral were declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987.

-

Hall of Ambassadors. Royal Alcazar of Seville

-

Grutesque Gallery. Gardens of the Alcazar

-

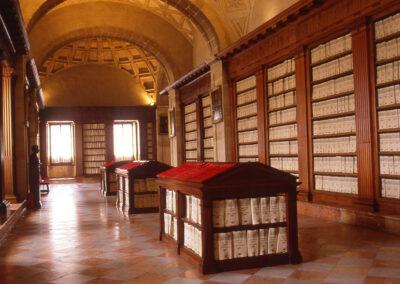

Hall in Archivo de Indias

The Royal Alcazar forms an extensive fortified palace complex, shaped over centuries through successive additions and renovations. Following the traditions of Andalusi architecture, the site is a harmonious labyrinth of interconnected spaces, styles and materials. Originating from the 9th-century caliphal palace, dar al-Imara, built upon earlier structures and fortifications, the Alcazar was later expanded and transformed by the Abbadid and Almohad dynasties, and subsequently by Christian monarchs such as Alphonso X, Alphonso XI, Peter I, the Catholic Monarchs, Charles V, Philip V and Isabella II. Traces of the earliest constructions can still be seen in the outer walls, which once enclosed the former parade ground — today’s Patio de Banderas.

The main entrance, the Puerta del León (Lion’s Gate), leads directly to Sala de la Justicia (Hall of Justice), a splendid example of 14th-century Mudejar craftsmanship, and to the Patio del Yeso (Plaster), the Alcazar Halls and the gallery overlooking the Patio de las Doncellas (Maidens), flanked on the right by the arcades of an Almohad palace. Further inside lies the Patio de la Montería, presided over by the spectacular inner façade of the Alcazar — that of the Palace of Peter I. This legendary king commissioned the construction of a sumptuous residence in the second half of the 14th century, today considered the crown jewel of Mudejar art. A bent entrance corridor leads to the private quarters, arranged around the charming Patio de las Muñecas (Dolls). Next to it is the official area, centred on the magnificent Hall of Ambassadors — inspired by the fabled Hall of the Pleiades built by King al-Mutamid. This majestic space features a grand domed ceiling, intricate tilework and elegant arches.

Just beyond its threshold, the Patio de las Doncellas brings light into the royal quarters and connects to the Gothic Palace built by Alphonso X and later renovated. Notable here is the collection of Flemish tapestries that adorn its walls. Beyond this, visitors discover the lush greenery of the Alcazar gardens: the mysterious, semi-underground Garden of El Crucero; the Galería de los Grutescos (Grotto gallery), with its richly ornamented Mannerist decoration covering the old Almohad wall; the Cenador (Garden pavilion) of Charles V, a perfect blend of Mudejar and Renaissance styles; and the Garden of the Lion, a baroque stage set of intimate charm, where an inscription pays tribute to the poet-king al-Mutamid. Flowerbeds, ponds, hedges and trees flourish here, stretching all the way to the ancient walls.

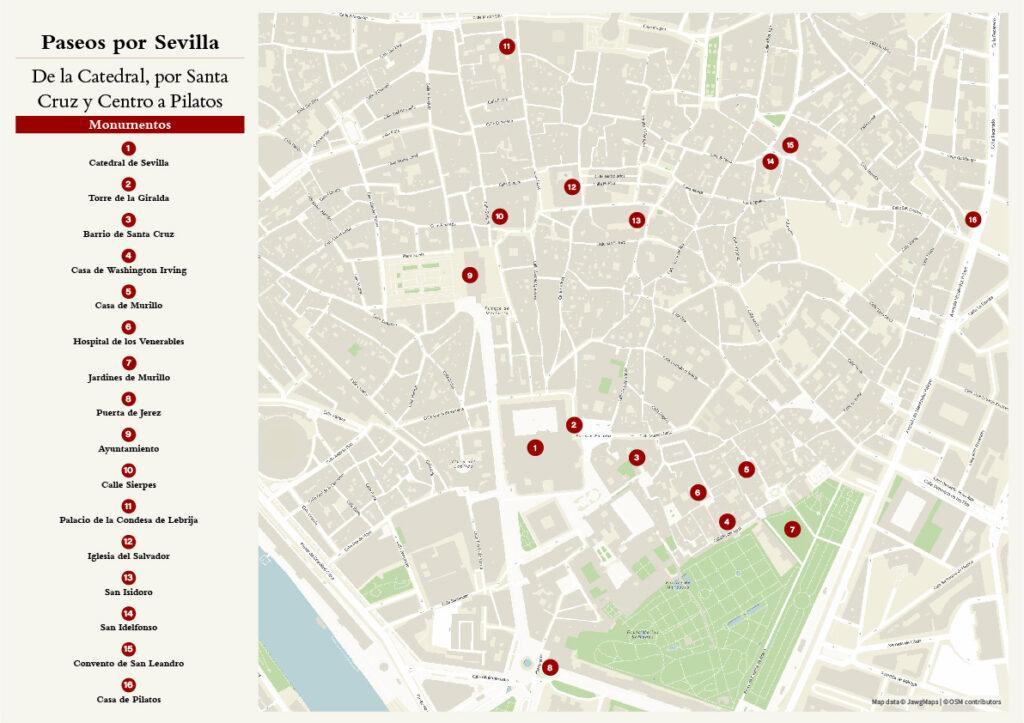

2. From the Cathedral, through Santa Cruz and the City Center to Casa de Pilatos

Seville’s Cathedral, the largest Gothic church in Christendom, stands atop the site of the former aljama mosque, built by the Almohads in the late 12th century. Set on a vast rectangular plot, the cathedral preserves elements of the original mosque, most notably the courtyard of ablutions — the Patio de los Naranjos (Orange trees) — with its arcaded galleries of pointed horseshoe arches, at the foot of the elegant minaret now known as the Giralda. This iconic tower, a symbol of Seville’s Hispano-Muslim heritage and cultural fusion, was constructed during the reigns of the Almohad caliphs Yusuf and al-Mansur, and completed in 1198. In 1568, Hernán Ruiz added a Renaissance-style belfry crowned by a weather vane that gives the tower its name. In terms of date and architectural style, the Giralda forms an exceptional trilogy with the minarets of the Koutoubia Mosque in Marrakesh and the Hassan Tower in Rabat. Beside it rises the vast body of the Christian cathedral, whose construction began in 1401.

Until the early 16th century, the cathedral’s vast Gothic structure was built with soaring ribbed vaults. Between the 16th and 17th centuries, new spaces were added, reflecting the influence of classicism — including the Royal Chapel, Chapter House, Sacristy and Sagrario (Sacrarium). The artistic heritage preserved within is of the highest order: from the monumental Main Altarpiece to masterpieces by renowned artists such as Martínez Montañés, Pedro de Campaña, Zurbarán, Murillo, Goya and many others.

Within the winding maze of the Santa Cruz quarter — bounded by the Alcazar walls and Mateos Gago Street — the very essence of Seville comes to life. In charming squares like Santa Marta and Santa Cruz, along Vida and Pimienta narrow lanes, every corner of this former Jewish quarter echoes with legends and the vibrant memory of its past. At No. 2 Callejón del Agua street stands one of the key stops along the route: a traditional Sevillian house with a leafy colonnaded patio, once home to Washington Irving before his journey to Granada. Among the many picturesque corners — from small shops and taverns to grand monuments — two sites especially stand out: Murillo’s House, a fine example of traditional Sevillian domestic architecture, and the Hospital de los Venerables, a splendid 17th-century Baroque complex, featuring a harmonious cloister and outstanding frescoes in its church.

-

Bas-relief by Mariano Benlliure. House of Washington Irving. Callejón del Agua, Seville. ©Galba

-

House of Murillo ©Andalucia.org

-

Hospital de los Venerables

It is well worth continuing the walk with a pleasant stroll through the Murillo Gardens, then circling the outer perimeter of the Royal Alcazar along Avenida de la Constitución, until reaching Puerta de Jerez, next to the historic Hotel Alfonso XIII.

Jardines de Murillo ©Andalucia.org

Continuing along the avenue, we arrive at the monumental squares of Plaza Nueva and Plaza de San Francisco, home to the Town Hall, whose early 16th-century Plateresque façade is richly adorned with intricate stone carvings. From here, Sierpes street begins its course near Plaza del Duque—one of the main arteries of Sevillian life and the very heart of the city centre. A hub of daily activity and commercial vibrancy, this area is full of cultural landmarks: at the Ateneo on nearby Calle Tetuán, the famous Generation of 1927 was formally founded; on Acetres street, poet Luis Cernuda was born; and on Cuna street stands the Palace of the Countess of Lebrija, one of the most striking and fascinating mansions in Seville.

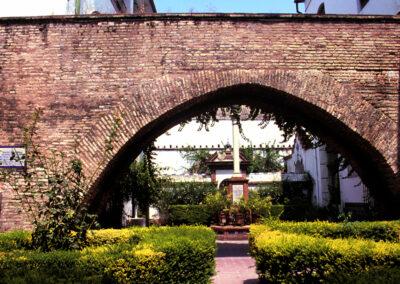

Just a short distance away, the Church of El Salvador marks the very heart of the city’s earliest settlement. The majestic church, built in the late 17th century, stands atop the site of the city’s first Great Mosque, erected in 830 during the Andalusi period. In the courtyard adjoining the church, remnants of the original Islamic structure can still be seen—columns and capitals at the base of what was once the minaret, now transformed into a bell tower. From here, a walk through the city’s oldest quarters unfolds along Plaza del Pan, the pedestrian street Alcaicería and the lively squares of Alfalfa, Candilejo and Cabeza del Rey Don Pedro. Along the way, the visitor will encounter the Gothic-Mudejar Church of San Isidoro, the striking neoclassical façade of San Ildefonso and the serene convent of San Leandro—famous for its handmade yemas (egg-yolk sweets), still produced by the cloistered nuns. This route eventually leads to one of Seville’s most emblematic landmarks: the Casa de Pilatos, a quintessential example of a nobleman’s palace with medieval roots. With the irregular layout typical of Mudejar palaces, the house unfolds in a maze of courtyards and rooms, showcasing one of the richest arrays of traditional craftsmanship and artistic styles in the city. Although construction began in the late 15th century, it was the first Marquis of Tarifa who, inspired by his pilgrimage to the Holy Land, gave decisive impetus to the building of the palace from 1521 onward. Renovations and additions would continue for decades thereafter. This magnificent residential complex—an exquisite blend of Mudejar, Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque styles—features many highlights: the intricately carved entrance by Genoese artisans; the main courtyard adorned with a graceful rhythm of arches resting on slender columns; classical sculptures and a gallery of busts; the surrounding chambers; the grand staircase; the endless tiled panels of vibrant azulejos (glazed tiles); the upper-floor salons decorated with frescoes by Francisco Pacheco; and the charming rear pavilions and gardens, complete with fountains, loggias and ancient artifacts.

3. Through the Neighbourhoods toward La Macarena and the Museum

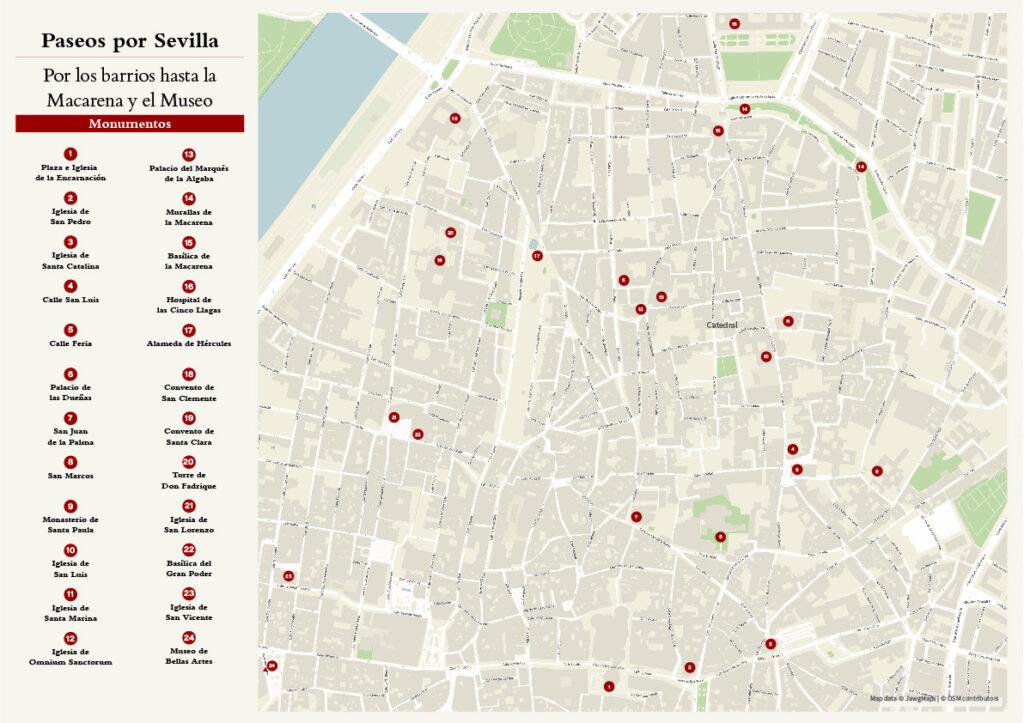

Download street map Walk 3: Through the Neighbourhoods toward La Macarena and the Museum

Download street map Walk 3: Through the Neighbourhoods toward La Macarena and the Museum

Starting from the squares and churches of La Encarnación, San Pedro—where Diego Velázquez was baptized—and Santa Catalina, a stunning blend of Gothic-Mudejar and Baroque styles, the visitor enters some of the most traditional quarters of the old city. These popular neighbourhoods are dotted with churches, convents, noble mansions and places full of authentic local charm. Their main thoroughfares are San Luis and Feria streets, the latter home to the historic mercadillo del Jueves (Thursday market), a lively street fair that evokes the spirit of the old Andalusi souks.

This area is rich in historical and monumental landmarks, led by the Palacio de las Dueñas, near San Juan de la Palma—a refined noble residence built between the 15th and 16th centuries, whose gardens were the setting of poet Antonio Machado’s childhood. At the beginning of San Luis street, visitors should take note of the Church of San Marcos, with its elegant bell tower reminiscent of a minaret, and the Monastery of Santa Paula, founded in 1473. Its small museum and visitable sections offer a sense of serenity and a glimpse into cloistered life. The handcrafted sweets made by the nuns are an added delight for those who make the visit.

-

Walls of La Macarena ©Andalucia.org

-

Church of San Luis ©Andalucia.org

-

Church of Santa Marina ©Andalucia.org

Further down San Luis street stands the former Church of San Luis, a magnificent example of 18th-century Baroque architecture. Almost directly across from it, the visitor will find Santa Marina, another fine example of the local Gothic-Mudejar style. On the parallel Feria street, the scene is enriched by the belfries of small chapels, traditional shops and the lively buzz of the market that unfolds in the shadow of the Church of Omnium Sanctorum and the Palace of the Marquis of La Algaba—adding a colourful and artistic flair to the walk.

At the northernmost edge of the historic centre rises the Puerta de la Macarena and a stretch of the city walls—the best-preserved section of the more than seven-kilometre defensive enclosure originally built by the Almoravids and later reinforced by the Almohads in the 12th century. Beside the gate stands the Basilica of La Macarena, home to the city’s most beloved Marian devotion. Just opposite, the grand façade of the former Hospital de las Cinco Llagas (Five Holy Wounds)—a Renaissance masterpiece from the late 16th century—now houses the Parliament of Andalusia.

-

Façade of Seville City Hall©Andalucia.org

-

Hall in the Museum of Fine Arts ©Andalucia.org

-

Museum of Fine Arts ©Andalucia.org

Heading back from La Macarena toward the river, the walk leads to the Alameda de Hércules—a pleasant urban garden laid out in 1574 over a former branch of the Guadalquivir. From here to the riverbank, the visitor will pass through a series of welcoming neighbourhoods—Santa Clara, San Lorenzo and San Vicente—each offering its own array of attractions. Highlights include the convents of San Clemente and Santa Clara, the latter incorporating the romantic 13th-century Gothic tower of Don Fadrique; the parish church of San Lorenzo, adjoining the Basilica of El Gran Poder, one of the city’s most venerated; and the Church of San Vicente. The route concludes at the Museum of Fine Arts, housed in a magnificent Baroque building whose galleries preserve a major collection of paintings—a brilliant summary of the Sevillian school, with numerous masterpieces by Murillo, Zurbarán, Valdés Leal, Pacheco and other renowned artists.

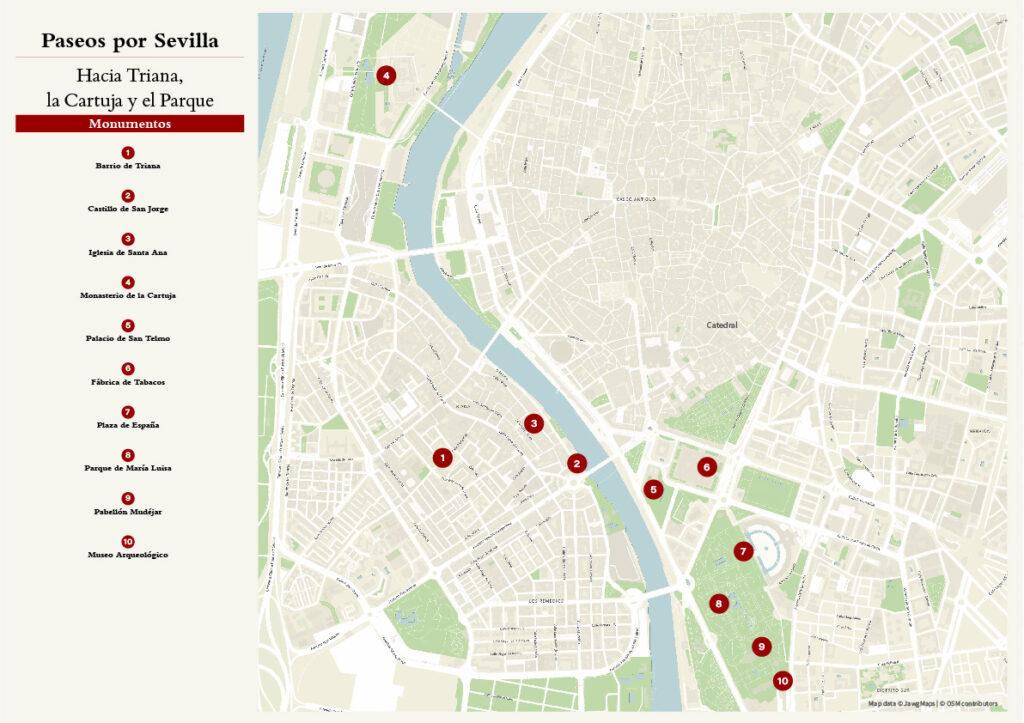

4.Toward Triana, La Cartuja and the Park

Beyond the old walled city lies, across the river, the Triana neighbourhood —a privileged bastion of Sevillian tradition that captivated every Romantic traveller without exception.

Triana neighbourhood and bridge

Its landmarks include the Castle of San Jorge, originally built by the Muslims in the 11th century, later used as the seat of the Inquisition, and now transformed into a market; and the Church of Santa Ana, where Triana’s most emblematic craft—ceramics—shines in all its splendour. Upriver lies the site of La Cartuja, a fascinating fusion of history and technology centred around the old Carthusian monastery.

-

Remains of the Castle of San Jorge ©Andalucia.org

-

Plaza de España. ©Andalucia.org

-

Entry to the Monastery of La Cartuja ©Andalucia.org

To the south of the historic center, the visitor will encounter the Baroque palace of San Telmo; the colossal Royal Tobacco Factory—an iconic setting of Romantic Seville, once filled with working cigar-maker girls and immortalized by Prosper Mérimée in Carmen; and the magnificent Plaza de España, embraced by María Luisa Park. The park’s shaded avenues and pavilions, built for the 1929 Ibero-American Exposition, are home to two must-see museums: the Museum of Arts and Popular Traditions, housed in the Mudejar Pavilion and the Archaeological Museum, which preserves treasures from Seville’s long and layered past.

5. The Surroundings

Seville’s surroundings offer a string of fascinating destinations, ideal for scenic day trips and outdoor getaways filled with history and charm.

El Aljarafe

The gentle rise to the west of the city—known as as-Sharaf in Arabic, meaning “elevation” or “high ground”—was one of the richest and most celebrated rural districts of al-Andalus. Poets of the time compared it to a constellation of whitewashed villages and hamlets scattered across a green firmament of cultivated fields, vineyards and olive groves. Today, a journey through the Aljarafe reveals countless corners where Hispano-Muslim tradition lives on in monumental architecture, landscapes and ways of life.

Perched along the ridge is San Juan de Aznalfarache, formerly Hisn al-Famy, site of the Castle of Buenavista. This stronghold was transformed by the Almohad caliph Yaqub al-Mansur—builder of the Giralda—into one of his favoured citadels. There, overlooking the vast Guadalquivir valley and the city of Seville, he celebrated his great victory at Alarcos in 1195. Downriver, along the banks of the river, lie the towns of Gelves, Coria, and La Puebla del Río — gateway to the vast plains of the Marismas (wetlands) and the threshold of Doñana National Park. To the west, a myriad of villages and estates are scattered among the olive groves.

Here, the visitor can discover places like Cuatrovitas, near Bollullos de la Mitación — a quiet, magical spot where the hermitage, a destination for pilgrimages, is an almost intact Almohad structure from the late 12th century. Aznalcázar awaits with its elegant Mudejar-style church, its pine forests, and the abandoned village of Castilleja de Talhara, also home to a Mudejar hermitage. Sanlúcar la Mayor preserves fragments of Andalusi fortifications and churches in the purest Mudejar style, while Valencina boasts exceptional megalithic tombs. Umbrete and many other charming locations complete this rich and inviting landscape.

-

Hermitage of Cuatrovitas. Bollullos de la Mitación, Seville ©Archivo Fundación El legado andalusí

-

Torre del Reloj in Sanlúcar la Mayor. ©Andalucia.org

-

Umbrete, vineyards ©Andalucia.org

Olives and Vineyards

The Aljarafe region, historically known as Seville’s pantry, has long enjoyed a reputation for the quality of its agricultural produce. Its table olives—especially the renowned gordal and manzanilla varieties—are justly famous, as are its excellent olive oil and wines: whites, finos, olorosos, and other traditionally aged Andalusian varieties.

Italica

Next to the town of Santiponce, along the N-630 road to Mérida, lies one of the most important Roman archaeological sites on the Iberian Peninsula: Italica, the city founded by Scipio Africanus in 206 BC to settle his veteran legionaries after the final defeat of the Carthaginians on Hispania’s soil. This aristocratic city was the birthplace of the emperors Trajan and Hadrian. The latter enlarged and embellished it, promoting its expansion in the early 2nd century AD. After a period of decline during Visigothic times, Italica was abandoned.

When the Muslims arrived, the area became known as Taliqa —the fields of Talca. Even the memory of the city’s existence was lost until its rediscovery at the end of the Middle Ages, when it became known as “Old Seville”, a source of inspiration for poets and, later, Romantic writers.

Today, its ruins captivate visitors just as they did in centuries past. Particularly impressive is the grand amphitheatre, estimated to have seated more than 20,000 spectators, and the noble residential quarter arranged around courtyards adorned with rich mosaic pavements, along with the remains of temples such as the Traianeum, baths, cisterns and other structures. Beside the present-day village of Santiponce, built in the 17th century over the original Roman settlement, stand the ruins of the theatre, and, further afield, the monastery of San Isidoro del Campo —a jewel of Mudéjar architecture.

An Admirable Sculpture

A testament to the openness of Andalusi culture, the sculptures unearthed in Italica stirred the admiration of Seville’s inhabitants at the time. The poet al-Hayyam dedicated enthusiastic verses to a female statue placed in a bathhouse —so beautiful, according to chroniclers, that it had driven more than one man to madness: It is a marble statue, proud of a neck whose complexion, rosy and white, is of the utmost beauty…