Osuna, landscape and figures

The flat profile of the Sevillian countryside goes along interrupted by the verticality of its towers, which rise over the cubist design of its urban layout. Whitewashed façades and stone are the supports over which the history of the city is drawn, whose splendour resounds in its grandiloquent architecture, in contrast with the minimalism of its popular whitewashed houses.

Just as we have penetrated the historic centre of Osuna, we can perceive the coming of Easter and, like a flash of lightning, the memory of Manolo Rodríguez Buzón comes to my mind. He knew how to sense the strength of those days, and through them marking the gap between Osuna and Seville, so far (or so near) as Córdoba, so equidistant artistically as Granada.

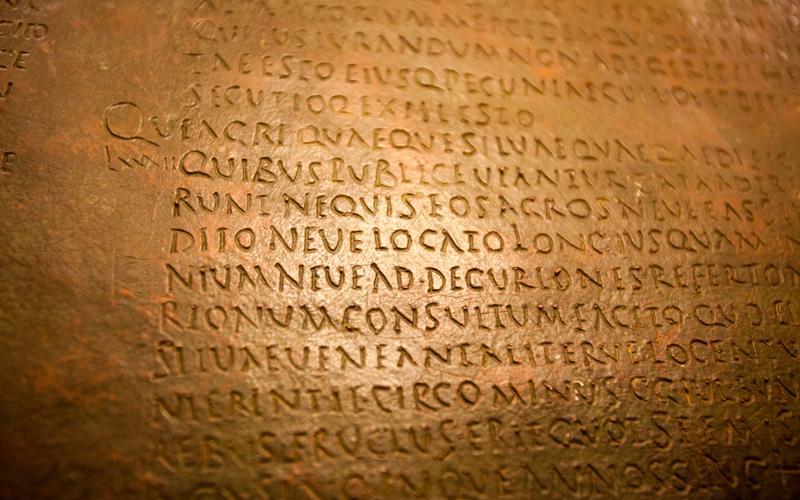

According to him, in spring there flourished rather than orange blossom, stone. And it is the conjunction of stone and whitewashed façades that enhances the antiquity of these streets. The invention of a Roman past was quite common in many Andalusian cities during the Renaissance period, but here, even though their Roman saints ̶ Saint Arcadius, León, Donatus, Nicephorus ̶ rather than in legend, it is true that Romans were in this town that glows its whiteness. Up there, in Madrid, the National Museum of Archaeology keeps the Bronces de Osuna (the Latin legal code given to Colony Iulia Genetiva) or the magic of that bull lying down, that seems an invitation to imagine the sun of Turdetania combing those hills of old. Unfortunately, the treasures of Osuna also gone to the Louvre Museum, lost probably forever.

A fragment of the so called Bronces de Osuna, a legal code where Romans inscribed municipal laws once the city was given the status to the city of Roman Colony Iulia Genetiva. German historian and archaeologist Emil Hübner, in his work Spanish Archaeology, highlights that these bronzes are the only authentic legal texts from the old European Roman empire that have ever been unearthed.

The Bull of Osuna is a sculpture carved by the Turdetani people, which was found in the archaeological site of the old Iberian city of Urso. It is a high relief of a lying bull included in a funerary monument.

If we can admire the copies of both the bronzes and the bull in the Archaeological Museum of Osuna, in the open air we can enjoy the beautiful rock sites at Las Canteras (The Quarries) ̶ whose exploitation started the Turdetani, the “heirs to Tartessos”, as Greek historian Strabo called them ̶ and the Roman necropolis, whose hypogea (underground tombs) still conserve the frescoes that decorated their interior, as well as the remains of the Roman theatre of the old Urso.

But still we are among the gateways and the strings of barred windows ̶ left and right ̶ in Seville Street and the convents and churches that line the way. Some of them are older than the houses, because the church of El Carmen may be Gothic or perhaps Plateresque. Others ̶ like that of the convent of the Espíritu Santo ̶ may be of the same age; yet, all the buildings are riddled with Baroque style, consecrated here as its own style precisely when it ceased being the official one in the 18th century.

Façade of the old court, located at the former palace of Govantes and Herdara, where its Baroque front is highlighted by imposing Solomonic columns.

The Century of the Enlightenment in which Spain endured darkness for a great part of it, saw how Osuna shone. Next to it, in which today a mansion is dedicated to culture, Manuel María de Arjona founded his Academy of Sile. In the lyrics of its anthem, older than the Marsellaise, we find its same heroic traits:

Of dark and dense fog

Covering Spain that infamous veil

And under its shadow ignorance

Extends its horrid sceptre…

… August brutality

Your throne sublime

In vile scum

Will come undone.

The Cilla del Cabildo Colegial in San Pedro Street.

On the left, a detail of its façade with the frontispiece in which is featured the Giralda tower of Seville. On the right, a full view of the façade in San Pedro Street.

But the Baroque of Osuna is deceptively Baroque and, of course, it is not the one that ̶ deceptively ̶ Seville started to show as the view of the yards in the palace-houses were open to the wayfarer in the beginning of the 20th century. They were, and they still are, as peaceful as convents, or even more. Inside them was born that Enlightenment from which Manuel María de Arjona was such an exponent, as well as his brother José Manuel, although in the opposite side, as he helped top put Seville on the map of tourists that were to come. And so did, one generation later, Antonio García Blanco, who gives name to the cultural foundation of the city, although his name was hidden over many years ̶ as was his funeral ̶ by his reactionaries.

García Blanco wrote in a book unknown today, Memories of a century, on the he tumultuous days that passed in the city during the final constitutional triennium of Riego, in 1823 in this square. Not far away from it, the Convent of Santa Catalina rises, housing in its enclosure that of the Conception. They both are standing there since the Golden Age, when farming wealth attracted nuns and friars in pursuit of fields and alms.

There is no doubt that one of its most remarkable Spanish figures was Francisco Rodriguez Marín, who was able to achieve the most complete compilation of the Cantos españoles (Spanish Songs) and collect from the humble people who gathered in the taverns those minimum literary pieces: the Comparaciones (Comparisons), last fraction of the literary movement of the Baroque period known as Conceptism.

In the Plaza Mayor of Osuna was the Puerta de Teba. The City Council stands where its old arch was and, at an angle to it, the Casino. This Domus Vivorum in a rural society was founded shortly after the War of Independence which here had its corresponding violent episodes. The ensemble keeps warm the remains of a culture that combined Mal Lara’s philosophia vulgaris of with the erudition of Antonio Nicolás.

The great work of Renaissance architecture of the Collegiate Church rests over a hillock rising over the Plaza del Ayuntamiento.

The corredera leads into the plaza, the traditional promenade that is in small towns as in cities like Vitoria. It was naturally the shopping street, and still remains something of that here, up to the Arco la Pastora, the old gateway of Écija, where it ends. There we can admire the Church of the Victoria, the Convent of Santo Domingo, whose 17th century mass holds many aftertastes of the previous century, and the same or even greater haughtiness of the Old Audience, the Municipality Granary, its stones heralding the splendour of its façade, the Osuna that showed off its wealth.

Archway of La Pastora (Shepherdess’ Arch).

In the diamond-shaped space that forms the corredera with the old road of the city of the towers, and the street that still recalls the road that linked this town to Seville, gathers together the most emblematic buildings, some of them as dazzling as the Palace of the Earls of Gomera (for years now turned into a magnificent hotel) and the Cilla del Cabildo ̶ the church authority for the granary ̶ , where those tithes and first-fruits, which we recited when we were children as one of the commandments of the church were kept.

This is the way to access to the true stronghold of the powerful House of Osuna, founded by a personage who, if he had lived in Italy, he would have been as mythical as the Medici Lorenzo the Magnificent: Don Juan Téllez de Girón.

Jaretilla street.

But we must leave the nearly flat Osuna to get to the one that ascends with difficulty towards the Colegiata (collegiate church). Streets are now secluded, like they were in all cities of our nobility, enclaves that were filled with the humble homes of the low-ranking officers when power became bourgeois.

While Emperor Charles V was fighting a war across half of Europe and Hernán Cortés was conquering Mexico for him, the 4th Earl of Ureña and head of everyone in this city was devoted to creating here all the splendour that remains, and much more that has gone. He was the one who put on the top of this hill the huge masses of the Colegiata and the University, still visible from many kilometres away, providing the skyline of Osuna with a refined shape.

He started to fill the temple with the works of art that stock it, from the Crucified Christ by Juan Mesa to the superb painting by José Ribera that is preserved and exhibited in the sacristy. From his eagerness resulted the façades, the altarpieces, the gargoyles, the display of canvasses and sculptures that still surprise visitors.

And to top off the Italian spirit, he built the Duke’s Pantheon in the Plateresque style of the Catholic Monarchs. He brought here Hernando de Esturmio, who had painted for the Cathedral of Seville his famous work ̶ the first one ̶ representing the Saints Justa and Rufina as the guardians of the cathedral since the time of the building of its foundations, from the times of the Almohads, thus in an anachronism full of lyricism. He arrived here to leave to us his allegory of the Immaculate Conception. He also brought from Sicily the alabaster image of the Virgen of Trapani.

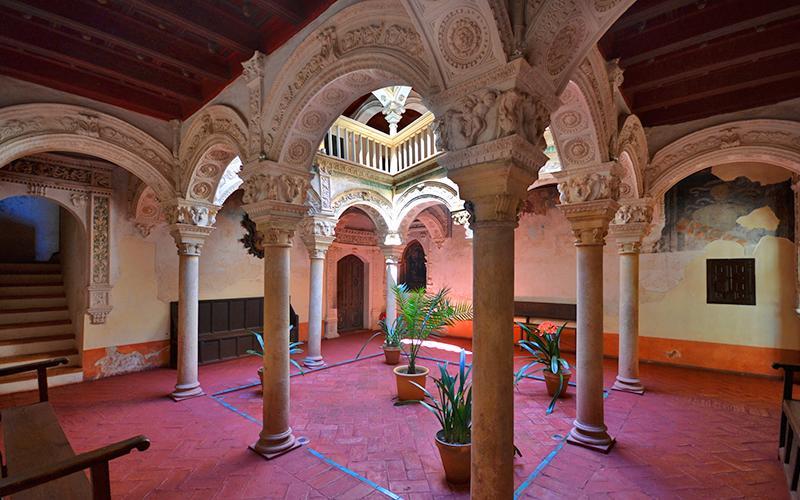

Interior and arcade courtyard of the Panteón Ducal (Ducal Pantheon) in the Collegiate Church.

In the early morning of Good Friday, Jesus of Nazareth will be taken up to the Collegiate accompanied by hundreds and hundreds of crosses, carried on the shoulders of an equal number of penitents to, in a unique show, welcome up here the dawn of a new era, that which consecrates spring as the mother of the year.

The pink stone of the University replicates that of the huge temple in its powerful rectangle, flanked by four towers topped with cones. Ureña left the most important works of this educational building to Esturmio: seven table paintings, among which the standout is an Adoration of the Three Kings, filled with candour.

Arcade court of the University.

In his decision to raise this tree of wisdom ̶ even then sometimes criticized as madness ̶ we may find the roots of that permanent transmission of knowledge that Osuna has displayed since then, century after century.

A little bit beyond the University rises the Convent of the Encarnación, a former hospital, meaning that it was part of the social structure with which the site was endowed in the mid-15th century. A great part of the Monastery has become the beautiful museum where their 18th-century plinths covered with tiles stand out. The most singular is the one which describes in detail the Alameda de Hércules in Seville, depicting a scene with the most varied people walking along.

Both urban and natural landscapes reflect the distinctive power of Osuna’s old and rich history.

From up here we can see the whole of Osuna, crowded with towers, belfries, and a playful set of roofs: a vision very much like that which surely would have been seen by Don Juan Téllez. It is impossible avoiding his figure. Nor the ones of those who, from the first Enlightenment until the Regenerationism kept the city in the spotlight of ideas.

It is impossible to remove all these figures from the scenery.

By Antonio Zoido

Writer