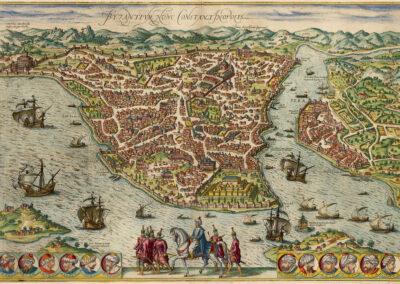

On May 29, 1717, the couple moved to their new destination in Constantinople, a city twice as big as Paris. Sir Wortley rented a 17th century palace in the neighbourhood of Pera, where the diplomatic corps was lodged. The house had a large terrace, gardens and beautiful views over the Golden Horn with the Bosphorus in the background. At that time, Mary, who was twenty-eight years old, was few months pregnant although she did not mention it in her letters. All along, the English aristocrat was not satisfied to be just the ambassador’s wife/consort; whenever her social duties permitted and concealed under a double veil and a long gown, she discovered the bazaars, mosques and public baths astonished at what everything she saw.

In mid-February 1718, Lady Montagu gave birth to a girl to whom she gave her same name, Mary. At this moment, the writer took advantage to discuss with doctors attending her during childbirth about the use of inoculation, which the Turks used as a smallpox vaccine. Convinced as he was that it was a fine method, she applied it herself in the arm of her toddler Edward, who recovered from it smoothly.

In May 1718 Lady Mary informed her friend Lady Bristol in a letter about her impending departure from Istanbul:

“I am now preparing to leave Constantinople, and perhaps you will accuse me of hypocrisy when I tell you this with regret; but I have become accustomed to the air and have learnt the language. I am comfortable here and, as much as I love travelling, I tremble at the inconveniences attending so great a journey with a numerous family and a child at the breast.”

On 5 July 1718, the Wortleys-Montagu boarded the Preston, a British Navy warship, fitted with fifty cannons and a crew of two hundred and fifty. From the desk, Lady Mary saw for the last time the dreamlike vision of Istanbul, with its mosques with golden domes and tall minarets outlined against the sky.

The journey by boat to England lasted five long months, although they made several stops on the voyage so as to know some places of interest along the Mediterranean coasts. The family separated in the port of Genoa: Their two children continued the trip by boat to England, and they did it by land towards north to Paris. They would arrive to London in early October and settled down in their old house at Covent Garden. The writer, who was thirty years old by the time, was a successful lady in the city, one whose presence was required in literary gatherings and who maintained good relations with the royal family.

Back to his home country, she experienced a huge smallpox epidemic. Her only concern was to protect her daughter from this terrible disease, and she decided to administer the inoculation, as she had done with her baby Edward in Constantinople. The “Turkish method” −which was used by Arab doctors since the 6th century− was brought by the aristocrat to England and became fashionable for a time until the Church acted and contested this vaccine, seeing it as a “Muslim heresy. Although she strongly defended the virtues of inoculation, it was definitively given up also because doctors preferred the traditional method of bleeding the patient. Mary was more than seventy years old when Edward Jenner “officially discovered” the vaccine in 1796.

A golden exile

Despite her social success, Mary could not fool herself: her private life was a mess and her marriage a farce. Her husband spent most of his time developing a coal mining inheritance that would make him rich in the future. Although he kept his seat in Parliament, he was further and further away from his career and his family. His son Edward did not bring him much joy either; he had become a wild and rampant boy who escaped from school and behaved with his mother in quite a wayward manner.

It was under these hard circumstances of her dull London life that she fell madly in love with a handsome Venetian poet named Francesco Algarotti −twenty-four years younger than she −, and she decided to abandon the city. In her fifties, the English lady longed to live abroad and to know other cultures. The relationship with her husband was increasingly tense, and her beloved daughter born in Constantinople had married recently Lord Bute −who would become the Prime Minister of King George III− and was living in Scotland by that time. Following her beloved Algarotti off to Italy was the perfect chance to abandon everything.

This was how the renowned Lady Wortley Montagu departed to Venice in July 1739 accompanied by two servants. Among her dearest belongings she took with her was the album with the letters she had written during her stay at the Embassy of Istanbul. She settled for a while in the beautiful city of Venice to wait for her lover to appear. Yet months unfolded and the beautiful Algarotti was still failing to give signs of life. Mary finally understood that her love was unrequited, but still she refused to return to London.

In the two following decades the writer became a sophisticated traveller, much admired both in Italy and France. After spending some time in Genoa and Geneva, she arrived in Avignon, where she moved to live in an old mill that she herself restored and made her home. Later on, she returned to Italy and remained a while in Brescia. She led a quiet and happy life there, playing cards with the monks from a nearby monastery, cultivating tea in her orchard, engaging in reading and passing summers by Lake Iseo.

When her death was near, her husband Edward Wortley, and her son-in-law Lord Bute, who was already the new favourite of King George III, and her daughter all exhorted her to return to London. It was not easy for her to abandon her quiet exile and return to England after twenty years of absence. During his return trip to her country, she was detained in Rotterdam because of bad weather, where she met an English clergyman, Reverend Benjamin Sowden. She entrusted him with her albums of Turkish letters, with the plea to keep them safe and to one day consider publishing them after her death.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu died in her home on August 21, 1762, a victim of breast cancer at eighty years old. She was buried the day after in the crypt of Grosvenor Chapel. Shortly before her death, she requested to a friend to publish under her name the two volumes she had handed to Reverend Sowden.

Her only wish after a long and errant life was to be finally recognized as what she was, a great writer and poet.

The first edition of the Embassy Letters saw light in 1763, and it was a great success. Its pages revealed a magical and sensual Orient, as seen through the eyes of a woman without the prejudices of her time and social position, which the general public discovered with awe. Voltaire confirmed the literary quality of the letters and spread her fame all over Europe, even saying that they were far superior to those of Madame Sévigné. Although the indefatigable traveller and writer could not enjoy while being alive this late recognition for her literary career, her dream, at least, was fulfilled.

Cristina Morató, journalist and writter.

Founding member of the Spanish Geographic Society and Member of the London Royal Geographical Society in London.

Hall of the Throne, also known as the Harem, in Topkapi palace.

The palatial complex is located in one of the highest points of the promontory known as Serraglio Point, overlooking the Golden Horn, right where the Bosphorus meets the Sea of Marmara.

In the last part of her life, Lady Montagu led a peaceful existence in different locations in the countryside. Later, when she was sick, she returned home to London where she died in 1762. She is buried there, in the Grosvernor Chapel.

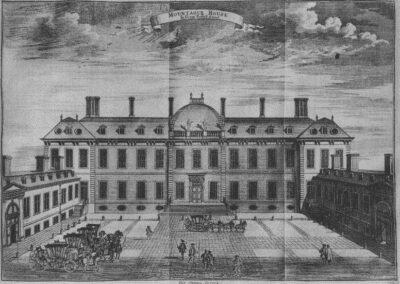

The first mansion of the Montagu family in London, in the neighbourhood of Bloomsbury.

The mansion was built between 1675 and 1679 and destroyed by fire less than a decade later. Once rebuilt in 1755, the building was sold to the government, which expanded it to house the first British Museum headquarters.