Ignacio de las Casas, a morisco wise Jesuit a peacemaker between two worlds

PART I

By César de Requesens Moll.

The upheavals that Granadan society experienced in the 16th century, after the uncanny finding of the so-called Sacromonte Leaden Books, and the Morisco issue, gave voice to Jesuit Ignacio de las Casas, he himself of Morisco origin, to search for solutions to the problem of his ancestors.

Son of Granadan Moriscos, Ignacio de las Casas’ (Granada, 1550 – Ávila, 1608) father was Cristóbal de las Casas, a prosecutor and litigation solicitor, and his mother was Gracia de Mendoza. He received his early education (1562-1568) in the boarding school of the Albayzín of Granada, an institution known as Casa de la Doctrina (House of Doctrine), whose teacher was Juan Albotodo, also a Jesuit of Morisco origin. Ignacio also studied Humanities (1568-1569), in Montilla (Córdoba) and Logic (1569-1570) in Cordoba.

Due to his lineage and the Moriscos’ situation after their revolt (1568-1571), he was admitted in the Society of Jesus, into the novitiate of Sant’Andrea al Quirinale in Rome (1573), where he was enrolled under the name of Lope Álvarez, and in 1574 in Florence as Ignacio López. In Rome he was an auditor of arts (1575-1578) and took private lessons in theology, judicial controversy, and legal cases, as well as Hebrew with a native master. There he learnt how to read and write Arabic under the chairmanship of Roberto Belarmino. In 1578 he moved to the province of Castile, where he was probably ordained. In the school of Segovia (March 1579) he already had the family name De las Casas (Delle Case, in the Italian documents). This very academic method resulted in his admission into the Society of Jesus, and after years of formation and study, he took his vows in 1603.

Tower of David in Jerusalem, illustration from the work Holy Land by David Roberts. (1842-1849).

When he was sent to accompany Juan B. Eliano in his mission of the Patriarch of Alexandria, assigned to the Society of Jesus by Gregory XII, he fell seriously ill in Alicante. In 1581 he travelled to Rome, where he was confessor in Saint Peter in the Arabic language. Thanks to his knowledge of this language, Gregory XII appointed him to accompany, together with Father Leonardo de Sant’Angeli and Brother Juan Francisco Lanza, Leonardo Abela, bishop of Sidon, in his mission to the Syrian-Orthodox and other eastern patriarchs (1583-1584). De las Casas, hampered by disease, could not travel with Abela and Sant’Angelo to Qara Amid, (today Diyarbakir, Iraq), but he visited twice the monastery of Qannoubine in Mount Lebanon, where he talked to the patriarch of the Maronites and carried out the priestly ministry with monks and parishioners. He also conducted talks with other Eastern Christians, as well as with Muslims and Jews.

After celebrating Easter in Jerusalem in the company of Abela and his Jesuit fellows, he returned to Rome in the winter of 1584. Once he was back in Florence again, he was specifically responsible for the Spaniards. In 1587, he was sent to Valencia to undertake the apostolate with the Moriscos. As a result of the dispute with the faquíhs he went through the relevant issues in Gandía (1588-1590) and Alcalá (1590- 1593), where he had the prominent philosopher and Jesuit theologian Francisco Suárez as his professor. His subsequent destinations were Palencia, Segovia, León, Logroño and in 1594-1595 Oran -in today’s Argelia-.

In Rome he helped Francisco Torres to translate the canons of the Council of Nicaea, the first ecumenical council of Catholic Church convened by emperor Constantine in the year 325.

He was occasionally an Arabic interpreter for the Holy Office in Valladolid (1596) and in the Supreme Council (1598), after the death of Jerónimo de Mur, who was the interpreter and grader at the Inquisition in Valencia (1602-1604).

He boosted the study of the Arabic language for training interpreters in Rome’s court, and theologians who were experts in ecclesiastic and koranic sciences addressed to the apostolate shared by Moriscos and Christians exposed to the influx of Islam. This was the same reason why he proposed to several pontiffs (Gregory XIII, Clement VIII and Paul V) the printing of Arab-Christian books and the production of a catechism for Moriscos containing the refutation of the anti-Christian doctrines of Islam, in which he was working in himself. In this sense, he strongly criticized the Catechisms published by patriarch (saint) Juan Ribera in Valencia for their lack of objectivity and mistakes regarding the koranic doctrines. But we cannot forget his own Morisco origin, namely, that his parents were converts and his grandparents had been good Muslims.

The Jesuit waxed lyrical about the Arabic language in the texts he submitted to Rome, recalling that it was one of the oldest languages on earth, disseminated in Africa, Asia, Far East and part of Europe, following the expansion of Islam.

Failure of the Moriscos to know Spanish was one of the reasons that led De las Casas to oppose the prohibition of the language. But also, being pragmatic on this respect, he warned of the dangers of provoking uprisings. He also argued that in the same way the priests who embarked to the Indies would be obligated to learn “new and more barbarian languages than this one”, and thus the church could not deny training a group of its missionaries in Arabic. He even proposed that the young Moriscos were the ones best suited to helping in the tasks of evangelization in their communities.

In Castile, converts and Mudejars were the most integrated, and hardly knew Arabic, dressed “like Christians”, could bear arms and take on diverse jobs, although they maintained customs like not eating pork or drinking wine and marrying members of their own community. In Aragon, there were the Tagarinos, who were blamed for practicing their religious ceremonies in public as well as secretly thanks to the persistence of the faqihs in their communities, to the contacts they had with North Africa and, also, to the fact that, despite that they prayed in Latin, they did not understand what they were saying.

“Los moriscos en el reino de Granada, dando un paseo en el campo con mujeres y niños.” (Moriscos in the Kingdom of Granada walking in the countryside with women and children). by Christoph Weiditz, 1529. ©Wiki Commons.

The rift between the two communities was increasing, and the situation of the Morisco population worsened more and due to the abuses of thethe clergy, the civil servants and the lords of the time. Together they were considered as plotters, allies of Spain’s enemies, spies or “fifth columnists”, particularly in the coastal areas where the incursions of the Berber pirates were frequent. There was a sense of collective paranoia as a result of the international tensions and the power reached by the emerging Spanish empire, which so many enemies had accumulated in only one century. The crown’s politics, increasingly repressive in its pursuit to eradicate any Islamic footprint in Spain, culminated in the publication of the “Pragmatic sanction of 1567” (also known as the Anti-Morisco Pragmatic) . Ignacio noted that the measures adopted, sort of a repressive arsenal against this people, had turned it impervious to the Christian message, irritating their spirit and highlighting their mixed feelings towards old Christian society.

Inequalities between old Christians and Moriscos was an issue that De las Casas also dealt with. The same Capitulations of Granada of 1492 recognized that “Moors will not give nor pay to Their Highnesses but the tribute they used to pay the Moorish Kings.” But the truth was that Moriscos paid almost double taxation. As a result of this arbitrariness, they felt excluded, which favoured the retreat on their own community, their roots, into their ancestors’ culture, to seek the comfort, understanding, and the recognition that the new status quo denied them. What De las Casas, together with figures such as the noble from Valencia Jerónimo Corella, the Franciscan Antonio Sobrino, or the arbiter Pedro de Valencia among others, proposed first was to attract them through good works, mainly peaching the removal of inequalities by removing fiscal discrimination. Bring them back with love, mercy and exemplariness was the basis of his message.

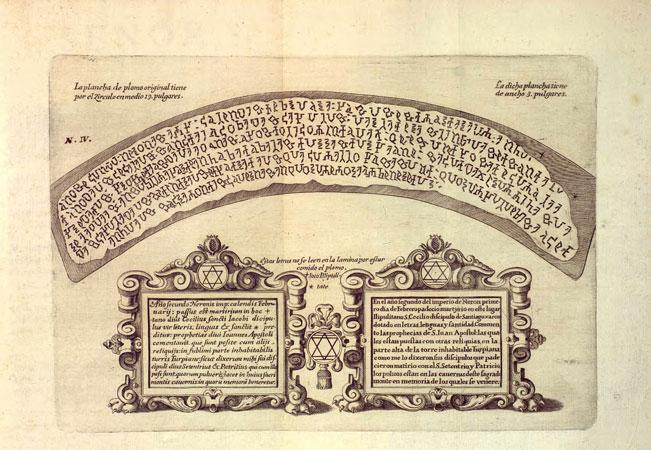

Etching reproduction of the Leaden Books, by Francisco de Heylan (1624), printed in Granada in 1741 in the Royal Printing House. [1]

Diego Nicolás Heredia Barnuevo. Mystico ramillete historico, chronologyco, panegyrico, texido de las tres fragrantes flores del nobilissimo antiguo origen, exemplarissima vida, y meritissima fama posthuma del Ambrosio de Granada…, el Ilmo. y V. Sr. Don Pedro de Castro, Vaca y Quiñones… Arzobispo de Granada, y Sevilla, y Fundador Magnifico de la Insigne Iglesia Colegial del Sacro Monte Illipulitano. / dalo a la luz pública el doct. D. Diego Nicolas de Heredia Barnuevo…

[1] Printed in Granada in 1741 in the Royal Printing House. Engravings on copper, mostly by Francisco Heylan on drawings by Lucenti, using the plates created for the Historia eclesiástica de Granada by Justino Antolínez, which remained unpublished. Digitised copy from the University of Granada. ©Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License

The implementation of the statutes known as “estatutos de limpieza de Sangre” (meaning “cleansing of blood) made the access to certain jobs and important posts in the structure of the State and the Church more difficult to new Christians (descendants from Jews and Muslims).

The “estatutos de limpieza de sangre”, which appeared in the 15th century, were adopted from 1556 by Philip II in the cathedral of Toledo. The Society of Jesus incorporated them in 1593.

Ignacio de las Casas called for the abrogation of the “estatutos de limpieza de sangre” as he considered them as denigrating and an obstacle to the Moriscos’ integration and conversion. They blocked access to the priesthood or to any other ecclesiastical office for new Christians, and he even requested the Pope to order “to burn all the processes of all the inquisitions, together with all the sambenitos, and that new Christians were not considered, nor called so, [sic] once a hundred years from their baptism had passed.”

Detail of The Inquisition Tribunal by Goya, showing a condemned man wearing a sambenito.

De las Casas stressed the interest in the Arabic language as a preaching language in Spain, but he, as we will see next, went much further, for according to him this language could contribute, as a language of evangelization, to the expansion of Christianity. The Church, thanks to well-trained preachers, knowledgeable in the language, culture and religion of Muslims, could extend its influence throughout the regions of the world under Muslim rule. Likewise, it could reach the famous eastern Christian communities (the Chaldean, Jacobite, Coptic and Maronite Churches) that were schismatic from the West due to the strangeness of their rites and the influence of local cultures.

As the Jesuit he was, Ignacio De las casas continued proposing the expansion of the Catholic faith, even though a language like the Arabic. The Ignatian essence of spiritual conquest even in the Islamic territories was Saint Ignatius de Loyola’s dream up to his death. The key in this invasion was the language of the Koran, which the very Saint Ignatius had encouraged himself to learn despite the prejudices in Spain against Muslim people. Yet, the Jesuit came against other evangelization priorities. In 1607, Spain was busy with the evangelization of American natives and its eyes were already set on the Chinese and Japanese.