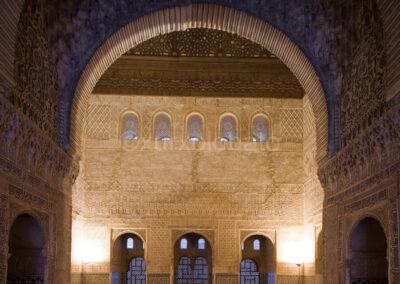

Ibn al-Khatib was more than a politician and prolific, polymath writer in the brilliant court of Nasrid kings Yusuf I and Muhammad V. His poems, inscribed on the Alhambra’s walls [1], did not foreshadow the tragic end of his hazardous life:

“With my jewels and my crown, I surpass the most beautiful

And before me bow down all the stars of the zodiac.

[…]

It is as though I had received the gift of that bounty

Which flows from the hand of my lord Abu al-Hajjaj. [2]”

Muhammad Ibn Abd-Allah Ibn al-Khatib was born in Loja (Granada) in 1313 and died in Fez (Morocco) in 1375. He was a multifaceted Granadan, as shown the many sobriquets and titles that he either named himself or were granted to him −depending on the positions he held−, and, also due to his personality and the circumstances of his life. The best known is Lisam al-Din (The tongue of religion), which does justice to his literary talent and his skills as a vizier, being conscious of the looming dangers to Nasrid Granada: its conquest by the Christian armies.

“Dhu-al-Wizaratayn” (The Double Vizier), was his official title as minister of the pen and the sword at the same time: “The Sultan −he confesses− has assigned me to ensure his secret chancery, a job reinforced by the army, the management of the Government and the Embassy missions accredited to kings… he has given to me his seal and his sword.” He suffered from insomnia, and he was said to be “the double-life-man”, for as he hardly slept, he had time to develop an incredible working capacity, being able to dictate, in one night, to a myriad of secretaries the Sultan’s edicts, the official correspondence, and … the history of a dynasty.

His death occurred by a summary execution in a dungeon in Fez; he was buried, disinterred and then buried again. He eventually was given a name as strange as fateful: “the man of the double grave”. And double, and even multifarious, was it so throughout his life.

Ibn al-Khatib’s personality, as it happens with all the great figures, is so complex that it is not easy to unravel his ultimate aims: whilst declaring himself loyal to his sovereign, he was charged with treason; he showed a supercilious treatment to his peers and a yet total humility before Ibn Ashir, the hermit of Sale. He moved surrounded by great pomp, boasting luxury, and yet he did not disdain to shut out the surrounding world in a mystical retreat with the ascetics of the hermitage of Chellah in Rabat, displaying a deep affectation following his wife’s death, whom she lamented in a lacerating poem. However, two months later he hastened to request a Moroccan Prince to send him a young Christian concubine. And what is more, he was not inhibited to write to his friend Ibn Khaldun, who had also taken a concubine of the same religion. He addressed to him some lines which were to become a double-edged sword, bordering on rudeness, where he expressed in a fun way an eventual partial impotence caught him by surprise in the presence of a beautiful young woman: “when drapes were closed”, −he writes− “and lovers are getting ready to enjoy their intimate moments, and the pharaoh dives into the waves…”

He enjoyed all life’s pleasures to the fullest, to the extent permitted by the fact of having been born into a family of dignitaries in Loja, having a great education, an encyclopaedic knowledge and his rank as minister in a splendorous Granada where he witnessed the building of the masterpieces of the Alhambra. He dealt with words with unparalleled eloquence, although his style showed an irresistible tendency, often annoying, towards over-complicated rhymed prose. However, the sense he gave to the descriptions of his journeys and pilgrimages were reinforced by deep observations, above all during his first exile in Morocco, from 1359 to 1362.

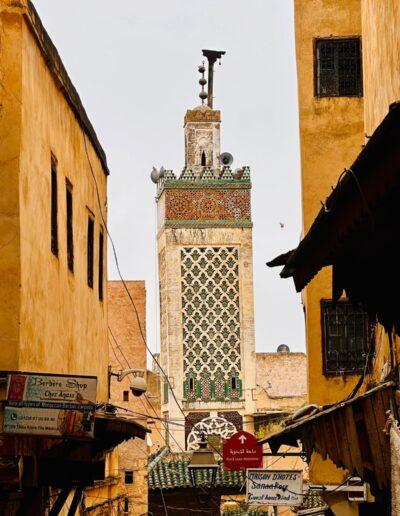

He could find beauty in an extravagant architecture, like the minaret in Aghmat, which he describes: “a place so ugly that it ultimately looked beautiful”, adding that this anomaly could well respond to its inhabitants’ nature −rather simple and poor in spirit.

He was equally a lover of poetry and he composed endless poems dedicated to the glory of the sultans or the Prophet on the occasion of the celebration of Mawlid (Muhammad’s birth commemoration) at the Alhambra, exquisite and delicate muwashshahs still sung around the world. In addition, few were the fields that were alien to him: legal treatises, the art of medicine, music, works on mysticism, travel accounts, therapeutics in relation to seasons, plague treatises, and many more besides. Yet, it was in the epistolary genre −as the letters he wrote on behalf of his sovereigns− where he was especially brilliant, as well as in the writings on history. Here, the value of his works lies in the fact of being a witness and a participant in the main events, for apart from using his expertise, he was able to insert into his works the official archive documents that he had drafted himself. The Iata is considered his master work, in whose ten volumes he describes the history of Granada and its men. In its introduction, referring to its contents, he explains that writing the history of one’s own country is a moral obligation recommended by reason and religion. That is the way historians devoted to this endeavour express the right to know the world they live in that citizens have.

However, Ibn al-Khatib’s greed for power resulted in a tragic end.

“Ibn al-Khatib as seen from the undersides”.The coordinates of a life The reference points to locate Ibn al-Khatib’s life might be six, and I am going to list them, begging not paying much attention to the order, for they overlap and influence each other: 1st. Zealous and exclusionary ambition to command, 2nd. Greed for wealth both material and immaterial. 3rd. Great passion for literary production (with overweening and relentless activity and utter disorder), associated with vanity and concern for his own international acclaim. 4th. Irresistible tendency towards obscure language, which was always perceived with a mixture of admiration and mistrust. 5th. An all-around rogue complex, which sometimes, following the trend of the times, he disguised as ascetism or mysticism. And 6th. The underlying consciousness that the Muslim domination in Spain was counting its days. E. García Gómez, Foco de Antigua Luz sobre la Alhambra. |

This could be this man’s life summary, whose qualities and faults were excessive. He was, until his death, loved by some and hated by others. The vizier was haughty and arrogant to the extent that even his disciples, the very same creatures he raised to the state’s highest offices, ended up plotting against him until his flight to Fez, where he was taken to prison, publicly humiliated in the presence of the Marinid court, to be eventually killed by coarse henchmen. His friend, the historian Ibn Khaldun, with whom he kept a tense relationship at times, lamented his death this way:

“… Ibn al-Khatib, who recently died in martyrdom, victim of his adversaries…” But what adversaries? These belonged to two bands, one from Granada, headed by Ibn Zamrak, his successor as vizier, and that of al-Nuhabi, who was appointed Granada’s qadi in chief by al-Khatib himself. The latter, of a more violent nature, comports by his behaviour with the Arabic proverb “beware the evil that those who you have filled with blessings can cause you”.

It is true that Ibn al-Khatib’s acerbic writing never stopped characterising the qadi as “Little obscene”, from whom he said that the only glory he achieved while in office was but to satisfy his gluttony eating figs. Here is an example of the kind of behaviour that brought wrath upon our persona, which became even more dangerous given the extreme confidence that had been placed in Ibn Zamrak.

This is how the conspiracy plot started rolling.

Across the Strait of Gibraltar, a second plot “anti-Ibn al-Khatib” started to develop. At its head was the Marinid minister Suleiman Ibn Dawud, who aspired to the position of commander of the “faith volunteers” in Granada, a title traditionally assigned by the Nasrids to a member of their own family. Ibn al-Khatib impeded Suleiman’s nomination, replying to the request “in a non-compliant way”, according to Ibn Khaldun. The settling of scores came swiftly. The political rapprochement between both courts, Granada and Fez, cleared the ground for both parties between 1372 and 1375, shortly before Ibn al-Khatib fled to Fez. The Nasrid monarch Muhammad V demanded vengeance on his minister, as he was convinced that such a departure was a treason.

Nevertheless, once Ibn al-Khatib had departed to Morocco, he was careful to send a letter to his Sultan Muhammad V. The document contained a poignant message. Its narrative was addressed to his laudable undertaking as a minister, hence trying to justify the reasons of his flight for carrying out his pilgrimage to Mecca.

From Gibraltar he made his way to Ceuta to reach Tlemecen, where the Marinid Sultan was waiting for him. According to Ibn Khaldun’s account, “his arrival was a high memorable event, and the Sultan offered him an unparallel reception”.

The end of the story? The disappearance of the Sultan, the numerous comings and goings between Granada and Fez, libels aimed at extraditing the “traitor. The process was completely rigged, as mullahs are known for, manipulating confusing phrases, taking them out of context in a surreptitious manner to be use as pieces of accusations against the “infidel”. However, given that the process did not reach a conclusive verdict, the conspirators decided to kill him in his prison cell by night.

Ibn al-Khatib, foreseeing his inevitable death, sent a last poem to Ibn Khaldun, where the last rhyme is -out and was used as the leitmotiv to underline the words mout (death) and knout (the end of the dawn prayer).

“Our sighs have stopped all at once, as the prayer does once pronounce the knout”

By Hamid Triki

Historian

[1]Verses of Ibn al-Khatib’s poems decorate both niches in the arch of entrance to the Chamber of the Ambassadors in the Alhambra.

[2] Yusuf I.

|

Bibliography:

|

Illustration by Jesús Conde.

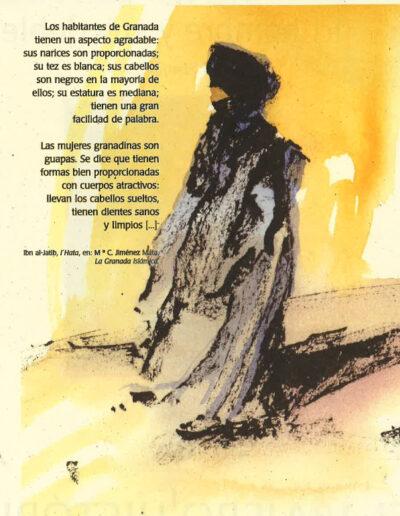

Granada’s inhabitants look very attractive: their noses are shapely; they are fair-skinned, they are mostly have black hair. They are medium high; they are very articulate. Women from Granada are beautiful. It is said they have well-proportioned figures abd attractive, were their hair loose and have wealthy, clean teeth.