Gerald Brenan, and the literary spirit of Bloomsbury in the Alpujarra

Gerald Brenan is considered the most outstanding Hispanist of the last century for works like The Spanish Labyrinth, The Face of Spain or South from Granada. However, aside from being a substantial writer and intellectual, he was an exceptional chronicler of the complex relationships within the intellectual world of his time in London.

It is rarely forthcoming that places as opposite as the exclusive London neighbourhood of Bloomsbury and the lost hamlet of Yegen in the Alpujarra kept up a romance so particular and intense as the one they enjoyed from the beginning of 1919 until the end of 1934.

Successive waves of illustrious visitors like Dora Carrington and Lytton Strachey, Virginia Woolf and Leonard Woolf, or Bertrand Russell visited Yegen and its most extravagant tenant: Gerald Brenan.

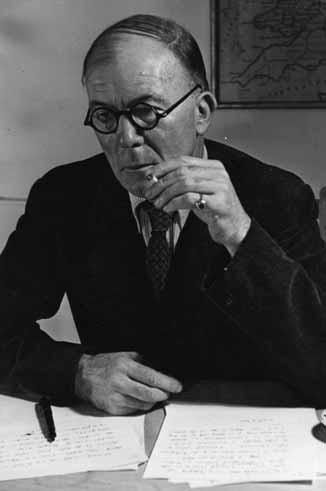

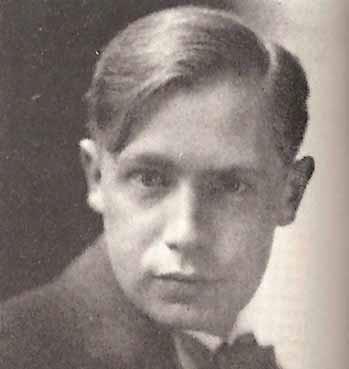

Portrait of Gerald Brenan, 1922.

Portrait of Brenan in Churriana, 1936.

Portrait of Brenan in his adulthood.

“Bloomsbury” was the name appended to a group of intellectuals that, during the first decades of the 20th century in England, revolutionized thought, literature, and arts. They began meeting —mythical gatherings that became part of the legend— around 1907, in the house of the Stephen sisters, later known as Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell. Among the attendees were E.M Forster, John Maynard Keynes, Lytton Strachey, Duncan Grant and the actual Woolf couple. If those in such a heterogeneous community had something in common, it was the great contempt they felt toward religion, and they raised pacifism as their identity banner, utterly abhorred Victorian morality, and they brought a breath of new fresh air to a stagnant artistic scene.

After fighting in the First World War and before undertaking his Spanish adventure, Gerald Brenan moved to London for a short period. Although he intended to begin his apprenticeship as a writer, Brenan entered the orbit of the Bloomsbury group and took part in some of its famous encounters, and social life became too intense.

From the beginning, he felt very self-conscious due to the overwhelming presence of people such as Virginia Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, or E.M Forster; and what is more, he felt inferior for not having had university studies. In his autobiography, Personal Record, Brenan described the whole philosophy and peculiarities of the group in great detail.

Deep down, the mythical encounters were no more than an excuse for enjoying a good conversation, with the condition that the new guest should not be boring: the worst of accusations in Bloomsbury, something that would even lead to a veto to participate in the famous gatherings. “I never felt identified with Bloomsbury as a group. There was no doubt about how brilliant their intelligence was, nor that their cult of good conversation made of the people whose friendship was fascinating […]. Civilized, liberal, agnostic, or atheist like their parents before them, they had always been outside the life of their times, always too little exposed to their confusion and violence to live it truly.”

Brenan wanted to go his way; he never felt comfortable in groups; he considered the literary circles as elitist, not much involved in the world, and fundamentally lacking in real human people. According to Brenan, “the Bloomsbury members “smelt too much of the University. They had been brainwashed and provided with conditioning based on class.”

Portrait of Ralph Partridge with the mountains of the Alpujarra in the background.

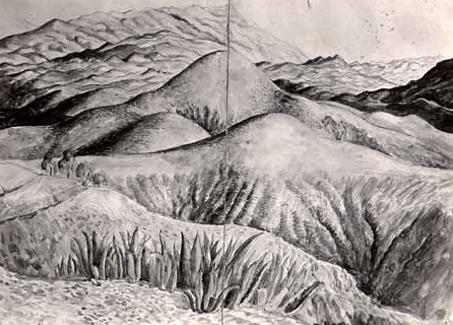

Drawing of the Alpujarra by Dora Carrington.

Therefore, his idea of leaving for Spain implied a retake of his education devoted to reading. He tried to recapture the time that the First World War had stolen from him. Andalusia was his particular University where he learned about himself above all.

Furthermore, he followed his way in life, the twisting path of literature. He wrote South from Granada, his most recognized work, an indispensable point of reference for modern ethnography, which recounts Brenan’s stay in a lost hamlet in the region of the Granadan Alpujarra at the beginning of the 1920s. It is considered a classic after 52 years from its first English edition.

The region of the Alpujarra is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada Mountain range. Fed by the almost inexhaustible supply of ice and the snow that melts from the summits more than 2,400 metres high, endless ravines and streams cross it. Romans started to build a network of irrigation channels here, which the Berbers concluded later in the Middle Ages.

Bruce Chatwin was another illustrious traveller who visited the region at the end of the 1970s. He did it to meet Brenan, comparing those lands with Afghanistan. Brenan’s biographer, Jonathan Gathorne-Hardy, made a brilliant analogy: the case of Brenan is as if today, an Englishman decided to settle in a remote hamlet in Afghanistan accompanied solely by two thousand books and the dream of being a poet.

The Alpujarra had a vast impact on Gerald Brenan: “I already knew then that I had never seen a more beautiful land than that Spain”.

Brenan established himself in Yegen on January 13, 1919. It was his home, sporadically, until 1934. Yegen is a hamlet with an architecture of Berber origin, a series of interconnected box-shaped houses without whitewashing and bluish-grey rooftops of launa. They were all built on the mountain slope; the streets were unpaved, only dirt and regularly protected by thetinaos, sort of porches with wood-beam ceilings that protected wayfarers from inclement weather. The animals lived in the lower parts of the houses. Colonies of fleas, ticks and flies thrived throughout. There was no electric light, running water, or toilets. He suddenly felt enamoured of the panoramic view of Yegen. The village was suspended at two thousand meters; everything remained chained to every sunset silence. Moreover, if any sound snuck out, it echoed along many kilometres.

“Oceans of air and the clouds,

like huge whales or enormous stranded ships,

hung over the hamlet,

anchored by the wet currents of marine air

that ascended until crowning Sierra Nevada”,

wrote Brenan.

Bloomsbury: secondary roads

Bloomsbury was not only a group of outstanding figures like Virginia Woolf, E.M Forster or John Maynard Keynes, as a significant number of narrow secondary roads, complementary and interlinked within, surrounded its centre. That was the quartet’s case, which comprised Gerald Brenan, Dora Carrington, Ralph Partridge and Lytton Strachey, who also was at the same time a distinguished member of the influential group. Their relation was a theatrical performance, a massive epistolary deployment –Gerald Brenan wrote around four million words in letters– replete with episodes of all kinds.

Dora Carrington, a brilliant and impulsive painter, was Brenan’s great love. They met in 1919, and the romance did not last long; they did not see each other much but developed a pen-pal sentimental relationship with dreamlike signs, or rather, a destructive dislike. The Alpujarras stage of Brenan was crucial to understanding that strange relationship. Yegen was a great discovery. Brenan was happy to a certain extent because he felt free and able to take part in real-life denied (or that is what he thought) in England, yet he remained a stranger in the village, periodically suffering devastating states of loneliness and boredom. Dora Carrington’s letters helped him persevere in his intention of staying on and becoming a poet. Returning to England meant claudication, kneeling before a militaristic and authoritarian father who disapproved of a son’s literary vocation.

One of the more entertaining chapters of South from Granadais that of the visit paid to Brenan by his friends, Dora Carrington, Lytton Strachey and Ralph Partridge, at the beginning of the 1920s. Strachey crossed half of the Alpujarra, from Lanjarón to Yegen, lying face down on a mule, observing the deep ravines in the road with panic while also bearing the pain of agonizing haemorrhoids. To make matters worse, after the torturous journey, he saw what the toilet of the house in the Alpujarra was, a chair with a hole that directly evacuated into a poultry yard. In short, it turned out that the stay was not easy nor comfortable. Days went by with the continual discussions of Dora and Ralph, Lytton’s face of disgust and Brenan’s sentimental tensions with the painter. Lytton described his journey as “death” when they were back in England. However, those words only increased the curiosity of the “Bloomsburians.”

Crying the Woolfs

The relationship between Yegen and Bloomsbury continued to be in full swing. On April 3, 1923, the Woolf couple, Virginia and Leonard, arrived at the tiny Granadan hamlet. Se quedaron cerca de quince días. They stayed some fifteen days. They stayed some fifteen days. Brenan knew them from London, where Virginia had already started to excel as an extravagant and Romantic figure. The Woolfs wanted to know Brenan more in-depth, mainly in the literary field, apart from getting around.

The conversation all day long dealt with literature, lasting around twelve hours. The Woolfs took the issue seriously. Virginia launched a continuous assortment of questions to Brenan, trying to annoy him, without being condescending, to test him. Little could Virginia Woolf expect that Gerald Brenan, whom she had briefly treated in London, and had already carried a burden of loneliness, started to speak tirelessly, burst after burst when they talked about literature.

Nevertheless, she also was a person who liked listening to others, and so she listened very much to Brenan, the lonely and eccentric Englishman from Yegen, who urgently needed company and conversation when the Woolfs arrived. He talked until he was blue in the face, according to Virginia Woolf, since he was aware that the Woolfs wanted to check his literary value. She defended Conrad, Thackeray and W. Scott, and she differed with Brenan’s high opinion of the Ulysses of Joyce. “Together with Proust, the best novelist of his generation”, according to Brenan.

Gerald Brenan describes the Woolfs in the living room of his home in Yegen at sunset: she, her angular face, her enormous, striking grey eyes that sparkled from the light of the fire, “her face revealed the peace of a poet,” wrote Brenan; he, stylish, masculine, with an everlasting pipe, taking part in the conversations with the strong voice of a great editor.

Virginia captivated Brenan, nothing like the romantic obsession that Carrington evoked; he described her as a person with a unique charm revealed at the peak of her conversation.

They also walked the surrounding areas of the hilly landscapes of the village. It was then when Virginia was at her best, brimming with youthful enthusiasm while gazing at the exceptional landscape of Yegen. “I recall her as a very different person, running through the hills among the olive trees and figs. She seemed to me, like an English lady born in the countryside, slim, scanning the distance with wide-open eyes, completely mindless of herself, under the fascination of the scenery and because of the novelty of being in such a remote and archaic place”, wrote Brenan in South from Granada. Nothing like the metaphoric “death” of Lytton Strachey.

When they left the house, they spoke not only of books but also about life, their friends in common and human relations. One of the philosophical maxims of Bloomsbury was liberty.

In contrast to the first wave of visitors, this second one was a complete success: “It is light, of course: a million razor blades have removed crust and dust, authentic colours resurface everywhere, the whiteness of vines; red, green, again the white of the huge, bowed, infinite landscape”, wrote Virginia Woolf in her diary.

Gerald kept up a regular correspondence with the Woolfs, and Virginia was sure that Brenan “shall write something very, very marvellous one of these days.” The truth is that he took a while, but little could Virginia suspect that she would end up being one of the characters of South from Granada.

Years later, having died Virginia Woolf, Brenan writes about her work: “Nevertheless, I am a great admirer of Virginia Woolf’s work. Everything she wrote presents that unusual feature of imagination we call genius. I perceive it better in the literary essays found in The Common Readerand its posterior volumes”.

Forever Friends, “Bunny” Garnet

David Garnett.

Ralph Partridge.

Gerard Brenan with his wife, Gamel Woolsey, in the living room at his home in Yegen, during Ralph Partridge’s visit.

Writer David Garnett is the third disembarkation from Bloomsbury. He arrived in Yegen accompanied by his wife, Ray Marshall; they enjoyed their honeymoon. Brenan knew Garnett during his journeys to London as a young apprentice poet. Apart from the friendship with Ralph Partridge, including their breakdowns and reconciliations, and V.S Pritchett, one of the most important and enduring relationships was that of David Garnett, “Bunny” for friends, which lasted until the latter died in 1981. An outlandish couple, talented and eccentric, Garnett had just published his successful work Lady into Fox and spent some relaxing days in Yegen, among walks and readings.

Other outstanding figures also visited Brenan, like the painters Duncan Grant, Roger Fry and Augustus John. However, the most relevant visit of the last wave, when Gerald lived his last stage in Yegen around 1934 and was married to the poet Gamel Woolsey, was that of the philosopher Bertrand Russell. Brenan doubted the old philosopher’s plans, who wanted to spend a vacation in such an exotic place as Yegen.

Bertrand Russell and the rural doctor

Bertrand Russell visited Yegen with Patricia Spence, twenty-one years old, whom he married shortly afterwards. They had planned to rent Brenan’s house during the summer. Brenan adored Yegen but thought that the house did not meet the standards for hosting a man of prestige and status such as Bertrand Russell, who moreover was more than sixty years old, and there was also that which made Brenan most fearful: he did not speak a word of Spanish. However, the old Russell, as the excellent philosopher he was, saw how the curiosity that Yegen inspired only increased at every attempt of dissuasion. Before leaving and letting them the house, Brenan and Gamel spent some days showing to them how to develop in that society.

If the Woolfs were astonished by their host’s boundless and tireless conversation, this time, Brenan ended up being more surprised at the couple’s simplicity and, above all, by the capacity to adapt to the inconveniences of a lost village in the Alpujarra. It is curious how the champion of the analytical philosophy, contemporary and friend of Wittgenstein, never complained about meals drowned in olive oil but otherwise not much refined, beds and their mattresses with lumps of wool, nor about the odours floating around coming from the stable and the subsequent flocks of flies.

Bertrand Russell and his wife Patricia Spence.

Nevertheless, Bertrand Russell’s adventure began after Gerald and Gamel left the house, not without teaching him some Spanish lessons and giving him a dictionary as a gift. In a pause between his readings, the philosopher ate some tainted canned meat in bad condition; Brenan’s servant, María, told him not to touch it, but he probably did not understand her. Russell suffered acute poisoning. Terrible fevers came to him, which even caused fear for his life. The doctor of the village got to save him miraculously. Brenan describes this episode in A Personal Record: “They called the doctor who, according to Bertie’s account, healed him by giving him a serum obtained from horse blood, and to explain it to him, the doctor had to get down on all fours, neighed and start kicking. Because, despite having a dictionary, Bertie had not learnt the corresponding word in Spanish…”. No doubt that Kafka would not have written anything better.

Although the visits of the English folks of Bloomsbury gave him joy, alleviating his loneliness, he also suffered some sadness, and when he was speaking about love with Carrington, of books with Virginia Woolf or of philosophy with Russell, in the background he was speaking about himself, about an eccentric Englishman who came to the Alpujarra looking for his own road in life, and in literature.