Benjamín of Tudela: through sacred geography

Benjamin of Tudela was ahead of other famous travellers such as Ibn Jubair or Ibn Battuta, who wrote about their journeys through works known as rihla, a genre in which our author produced his travel book Sefer Masaot.

The account, of an anthropological nature, collects observations from the countries he visited in the 12th century, with emphasis on Jewish communities.

It is told that Saladin, in need of money to keep fighting against the invasion of the Crusaders, called a rich Jew to confiscate part of his fortune and destine it to undertake this task. Yet, the lenient Muslim sovereign may have granted an option by proposing him a conundrum. He asked him which faith was the best; in case that the Jew responded that it was “Judaism”, that would show a lack of respect to the faith of the sultan; if he answered “Islam” he was an apostate; in either sense, there was a pretext for the forfeiture.

But the Jew offered in response an uplifting story: “Your Excellency: there once was a father who had three sons and a ring adorned with a precious stone, the best in the world”. The three sons begged the father to leave them the ring when he died, and the father, to please them all, called a goldsmith and asked him: ‘Sir, make two rings similar to this, and put a precious stone in every one of them just like this one”. The master smith made two rings so identical that nobody could distinguish the real one. He called the sons separately and told the secret to everyone, and everyone thought he had received the true one, which only the father knew for sure. “It is the story of the three religions, your Excellency. The father who has given them knows which one is the best, and every son of him, that is to say, us, believe we have the good one”. The sultan marvelled, and let the Jew go without anything being demanded.

In his journey through Palermo, the Pearl of Sicily, Benjamin of Tudela might have heard this story which was later registered by the unknown compiler of the Novellino (collection of tales written by anonymous authors in the 13th century in Tuscany, Italy).

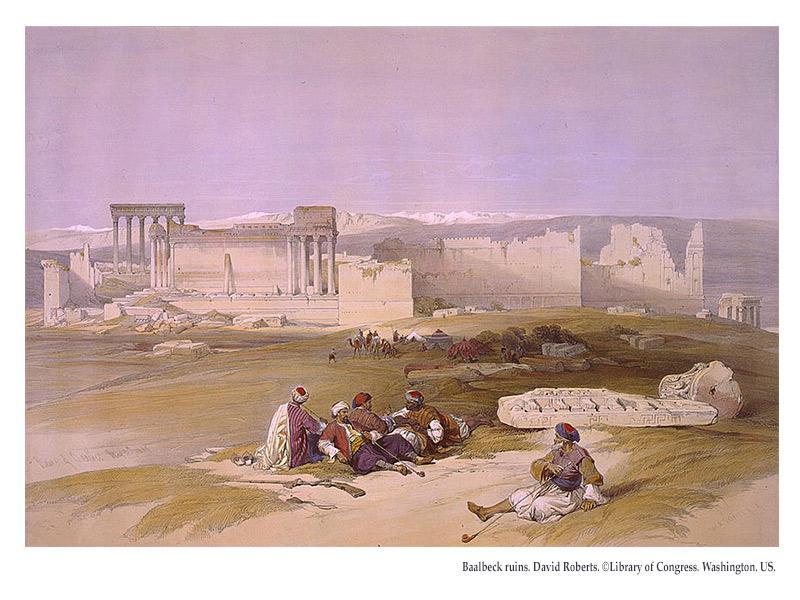

And the same prosperity that his co-religionists settled in Dar al-Islam enjoyed filled him with joy during his passage through Baghdad and Damascus. I met this brave traveller for the first time one day among the notes of an old volume, in Tadmur, amid the ruins of Palmyra. Next time it was in Iran, when visiting the ruined ziggurat of Borsippa, which Benjamin had described, confusing it with the Tower of Babel, as it is seen nowadays, “cloven by God’s fire”.

But who was this Jewish Marco Polo, who was to achieve such an extraordinary odyssey, from his native Tudela to the Indian Ocean and China of the Tartars? Little we know of him, excepting that he probably travelled between 1165 and 1173 and died towards 1175, without having much time to either write or to organize his numerous observations. The anonymous writer of the prologue, who was also in charge of giving definitive shape to the book, presented him to us as an extremely discreet person and very well educated, knowledgeable of the sacred texts and ancient history. He wrote his SeferMasaot [1] or book of travels in Hebrew, without doubt the lingua franca during his itinerary, but he should have also understood Arabic and even Greek and Latin. These trilingual Jews were very famous in al-Andalus, and their help as ambassadors, counsellors and translators was invaluable. The 12th century, to which our traveller belonged, was admirable as it shows us a multifaceted panorama: that of the School of Translators of Toledo; that of the Granadan Mosheh Ben Ezra ̶ author of the most important treatise in Arabic on the theory of Jewish poetry, considered the number one in the Golden Age of Hispano-Hebrew poetry ̶ in short, the century of Maimonides the Sephardic, who wrote in Arabic most of his theological treatises and was a physician in the caliphate of Cairo. How can we fail to recognize the decisive step represented by Benjamin of Tudela, a very image of that universal Jew, with the openness of character that the courts of al-Andalus brought about and cultivated? Without abusing the idealized stereotype in the medieval context of an image immune to conflicts, the coexistence of the three cultures in al-Andalus soil, speaks to us of a religious relativism, in this case perhaps even more expansive than it was believed. Our cities have preserved in their Aljamas and Jewish quarters the traces of a segregation in the urban space, which was perhaps the formula to include the other. . That is the diversified world to which Benjamin is devoted with great enthusiasm, in my opinion the most redeemable of his account.

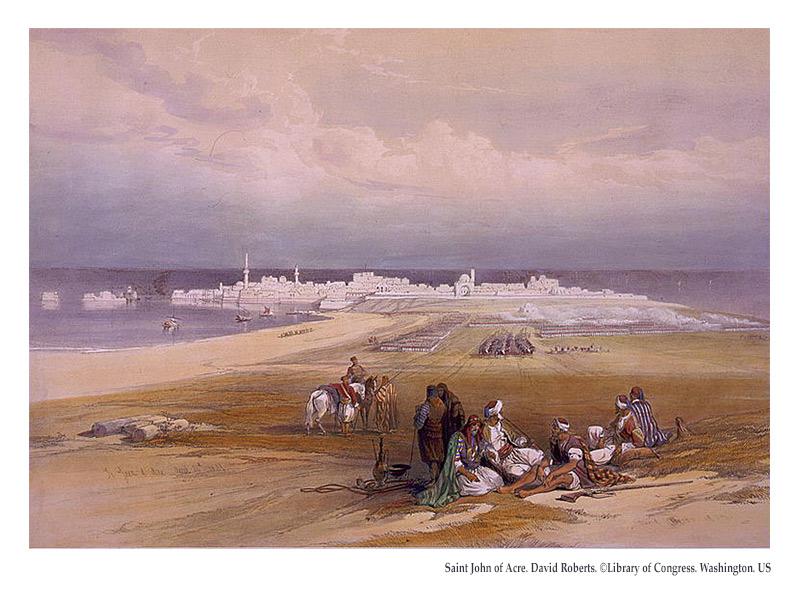

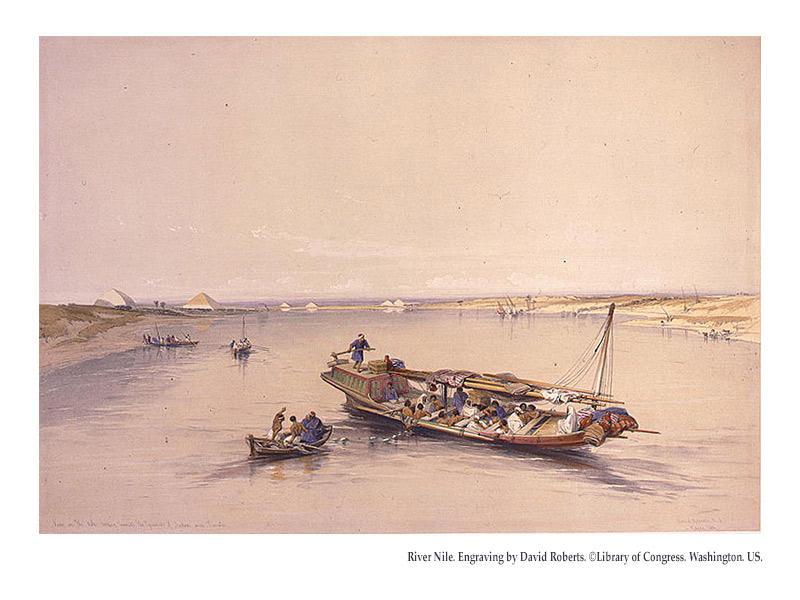

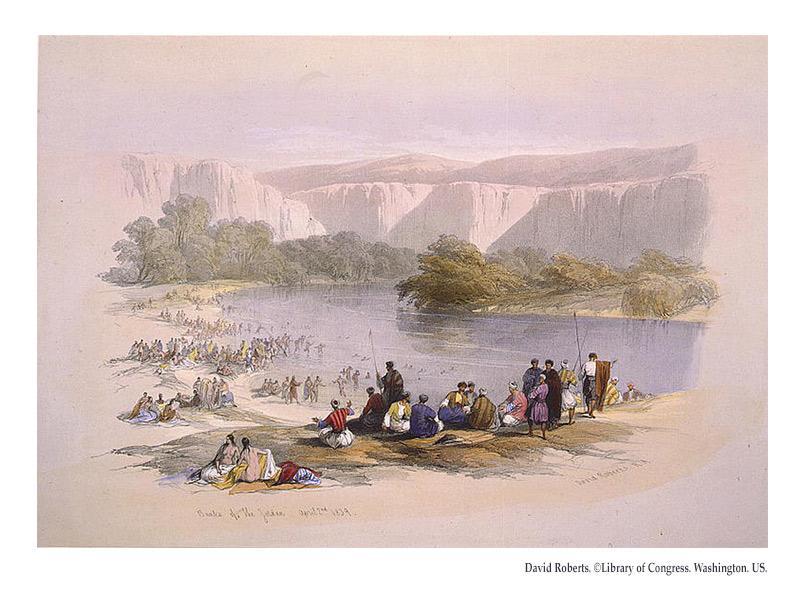

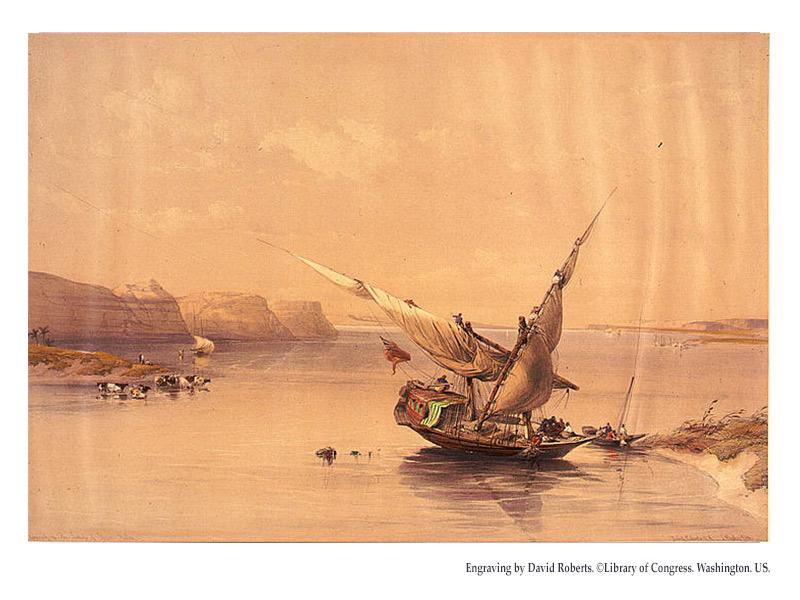

Furthermore, the Sefer Masaot is akin to a geography treatise, or to the travel accounts (rihla) inspired in the Arabic concepts of the era. Its main aim was to inform about the social and cultural situation of the Jewish communities all over the known world. Hence, the book has become an essential source for knowing the Jewish economy, demography, and culture of its time. Nonetheless, if the Jewish population and the name of the community counsellors and managers are to be the most important items to account for Benjamin, his interest is far from being reduced to the scope of the Hebrew world, and to the most prominent historical events at that moment ̶ the Crusades, the schism of the papacy and the conflicts in the Orient during the fall of the Fatimid Islamic dynasty ̶ did not escape his attention. He mentioned the School of Salerno and the fact that the city of Sorrento had found an oil called petroleum that was used as a remedy. He was both interested as much in the pearl cultivation in the Persian Gulf as in the fishing techniques used in the Nile.

Benjamin of Tudela paid as much attention to the pope of Rome as to the caliph of Baghdad, the sultan of Cairo, or the Exilarch of Mesopotamia. And the Jewish Encyclopaedia cites him as the major source of our knowledge about the messianic claims promoted by David Alroy that had arisen some years before his passage through the region.

Benjamin has always excited the attention of scholars. What was the purpose of his travels? Why was his attention to the Jewish crafters specialized in dyeing almost obsessive? Was he a dealer interested in the business of precious stones? Was he an emissary of the rabbinical academies who approached the peninsula for material assistance? A pilgrim among the many that undertook the way to the holy places? If we take into account that the idea of the homo viator (travelling man) is the utmost metaphor of the Middle Ages, and we add to this the importance of such errancy in the Jewish culture, and if we also value in addition the 12th century as a scope of economic development and intellectual and spiritual rebirth or renaissance, then it can be understood how the diverse modes of travel (pilgrimage, vagrancy, trade, geographic exploration, study travel or scientific research), constitute the clearest signs of the expansion of mental horizons of the time. It was the unusual mobility of the members of the Middle Ages that led to the discovery (but also to the invention) of the Other.

In Cairo Benjamin had counted not less than seven thousand Jews, very rich and scholars of the Torah.

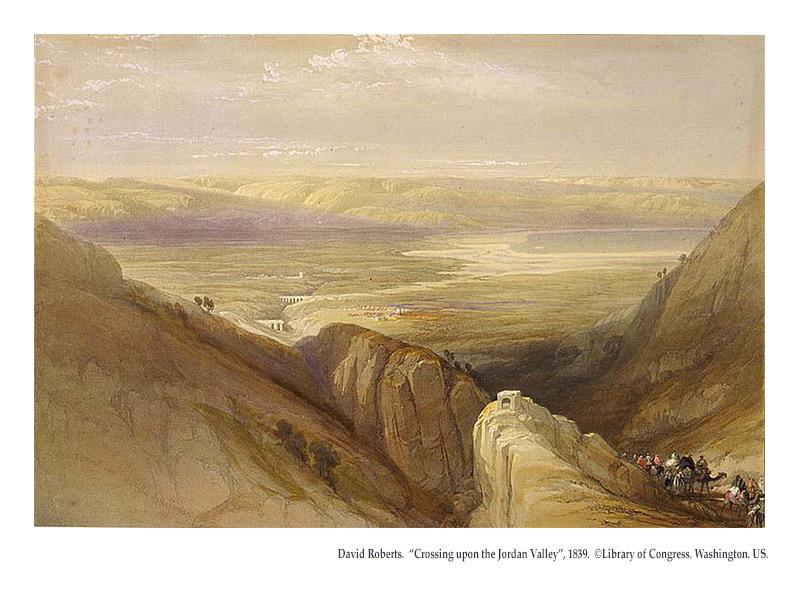

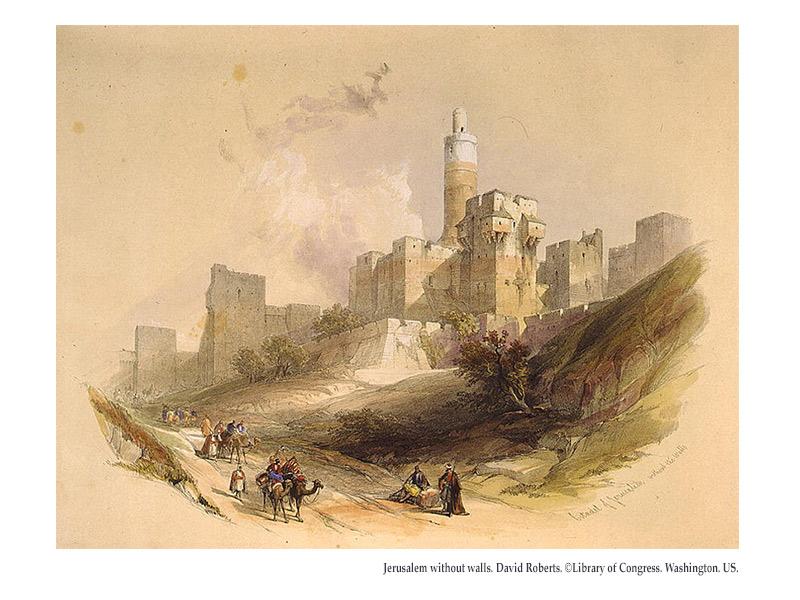

As for Benjamin of Tudela, the economic and commercial interest was to meet, without doubt, the desire to list the biblical sites. Once in Holy Land, his interest in the Tombs of the patriarchs awakened, and it was this curiosity what marked his whole journey through Mesopotamia. Thus, he revered the tomb of prophet Ezekiel ̶ the Hebrew equivalent of Santiago de Compostela, which attracted a crowd of Jewish and Muslims ̶ marking other stopovers along the sacred geography. But rather than being satisfied with a mere inventory, as were many of his contemporaries, Benjamin conceived his book as a sort of “Guide” for the use of pilgrims, giving directions on distance or the name of institutions or individuals who might provide hospitality to the walker.

His vocation of geographer or ̶ we would dare to say ̶ of a precocious anthropologist and journalist, took him to record those facts that reached his eyes and entered his ears, and which he considered curious or worth mentioning. As a trader he exalted before the feverish life of the Arab souks; as a pious Jew, he mentioned to us the House of Solomon in Jerusalem; as a man of his time, he showed his amazement at the wealth of the East.

He tells us about the pearl fisheries on the Malabar coast; he reported the human diversity swarming the streets of Cairo, a crossroad for all traders of the world; the Roman architectural marvels that almost paled when compared to the mosques of Damascus and its crystal wall “made by the art of charmers”.

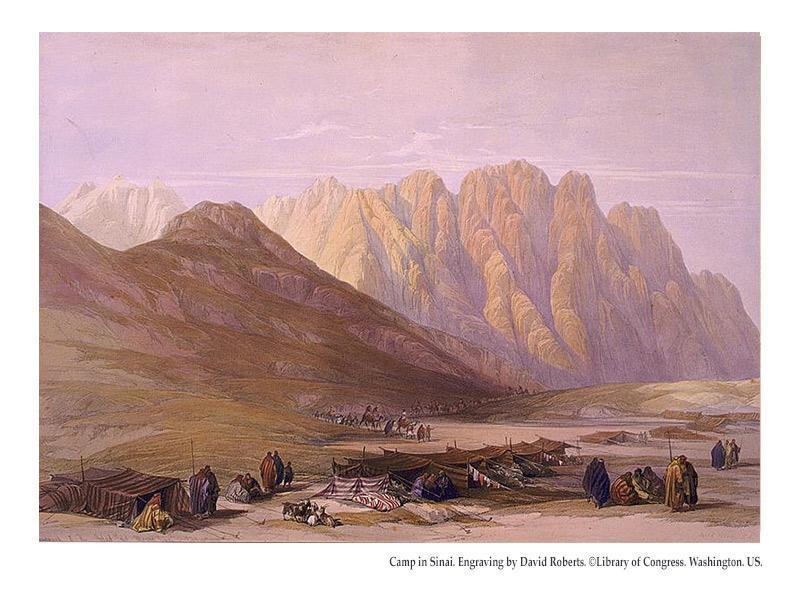

His itinerary has gone through the critiques of many impugners as well as learned apologists. Historians have used his book for economic and political history, not without considering at the same time its legendary elements. Some see him as another Manderville, who supposedly travelled the world without leaving his hamlet, while others prove all his tour was feasible. What is certain is that Benjamin of Tudela mixed the descriptions of the countries that he visited ̶ the northern Mediterranean area, Middle East, Iran and Egypt ̶ with the remarks on other countries that he should have known by hearsay, such as Germany, Russia, Yemen, Ethiopia, Ceylon and China. Regarding these last regions, the account turns more general and vaguer, allowing the appearance of what in the Middle Ages was a commonplace: that of wonders.

While the Mediterranean is considered to be the sea of rationality and civilization, the Indian ocean is to be interpreted as a “Counter-Mediterranean”, the space of all prodigies. Medieval “Reason” produces monsters. Not missing in Tudela is allusion to the giant Eagle of the frozen seas of China, another version of the Rujj, the legendary bird that appears both in the Arab and Christian writings, from Abu Hamid al-Garnati to Marco Polo, to a place of honour in Borges’ work Manual de zoología fantástica. Also, the fabulous wealth of gold, spices, and precious stones, as well as perfumes (that “scented myrrh from the faraway Tibet”) with which the western imagination adorned the eastern lands.

The East represented the utopia of refinement and abundance, arousing the greed for unimagined luxury in people’s minds. Located at the end of the Medieval European world, Byzantium was an almost unreal bridge to a barbaric world of a mysterious and exotic Asia. There Benjamin finds the biggest churches and the most sumptuous palaces, such as that of Blanchernes, with “a throne of gold and noble stone and a golden crown […] with countless precious stones, so many, that by night it is not necessary to use lamps there, for everyone can see the luminosity of the precious stones. And yet, “Greeks from the country are rich in gold and precious stones, they wear silk garments with gold trims woven and embroidered on their vestments”, which to our traveller appeared effeminate, maybe early symptoms of the decay of the Empire.

In all, I understand that the most valuable judgment lies not in what is a fake, but in exploring why those two fields are mixed so freely. The reason why this preference for recording the extraordinary is something usual at the time, if the western mirabilia are reflected in the Arab °aja’ib (prodigies), this is due to the fact that in both traditions “marvel” constitutes the key to translate difference, a way of knowing the other.

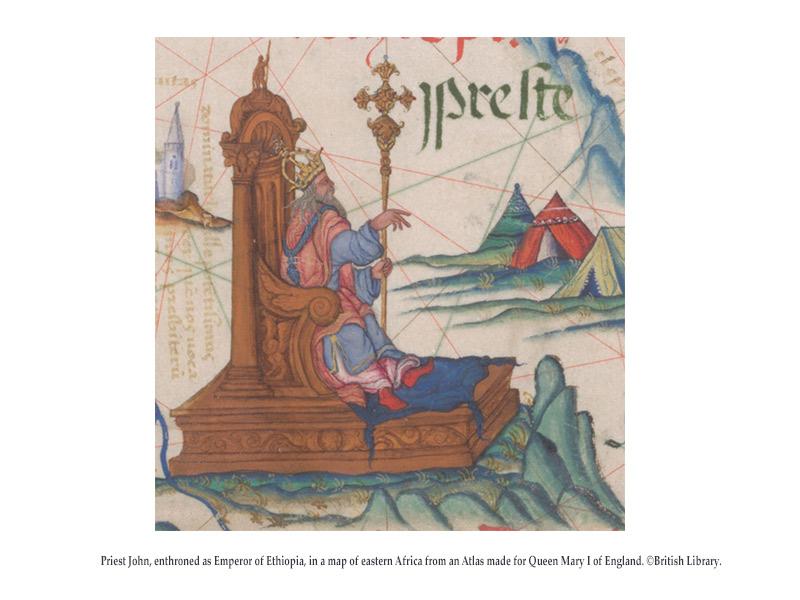

Moreover, the Sefer Masaot is one of the first works to echo the legend of Prester John, the Christian monarch who menaced the empire of Saladin from the East and would save Christian Jerusalem. Benjamin tells us the story of the alliance between Turkish infidels and Israelites, as well as about the defeat that they inflicted on the king of Persia, heard directly from the participants in the conflict. In those days, there was even a letter doing the rounds addressed to the Byzantium emperor by Prester John saying that he was the owner of the Ydonis river that was said to come out from paradise filled with emeralds, sapphires, rubies and… pepper!

Our scientific and positivist sensibility is struck as we see recorded, next to these legends, accurate descriptions of other phenomena our traveller met, like the Nilometre (“twelve cubits above sea level”) and the Alexandria Lighthouse (visible “at one hundred miles”).

Compared to western pilgrims, who did not discovered Islam until the 13th century, Benjamin of Tudela has left us precious information about the “other world”, a good world he discovered in connection with his wanderings.

In a rather impersonal account and sparse in descriptions, he underlined the attention given to Baghdad, which he had the fortune of visiting before the Mongol invasion. A land of palm trees, orchards and fertile plains “where people from all countries come with merchandise, and there are wise men there, philosophers who know all sciences and magicians of all types of enchantments”. While the traveller from Valencia Ibn Jubair, who visited the area some ten years before, did mention that most part of the buildings had disappeared, remaining a Muslim city only by its prestige, Benjamin does not find words to translate his admiration. “The caliph is extremely rich and respected by the princes of Turkmenistan, Persia and the Tibet. Even more: he is infinitely wise. He is dressed in regal clothing made of gold, silver and linen, and wears on his head a turban with precious stones of inestimable value. Over the turban, a black headscarf symbolises his humbleness before earthly things, as if to say: ‘see, all this honour will be covered by in fog on death’s day’”. In the shadow of this pious man, learned in the Torah of Israel, forty thousand Jewish live “in peace and honour”. Not only synagogues flourished; there is also a “House of Wisdom” and even hospitals for insane people, such as the Dar al-Maristan, where those who go insane due to the heat are cared for until they are able to leave sane and free in winter.

Compared to the bookish experience of this space that Christian pilgrims had, aliens to the reality in which they were walking, our walker’s practical sense helps to open the eyes to others. Compared to the vision of the impassable universes that the Crusades promoted, our sharp merchant senses without sarcasm the “inter-confessionalism” of trading.

The hazards of the sea, the pirates of the Barbary coast, fever or the fatigue of the journey that so much humanize explorers’ accounts, are however not included in the Sefer Masaot. Little we know about his personal and intimate journey despite he should not have lacked patience, nor money, nor faith. We only know the miles, the leagues measured by carriage, the points between two transfers. The walker is blurred; he is himself the road. Nomadism becomes natural movement: nothing is definitive. Benjamin hardly survived his journey: the cycle of his errancy completes his life. But before, the adventure of the man coincides for a moment with the adventure of his saying: exile culminates in writing, in the Book: the only homeland.

Mayté Pérez. Hispanist.

[1] The first edition came to light in Constantinople in 1543. We can find a study on the vicissitudes of the book and its translations in the first edition by José Ramón Magdalena Nom de Deus:Libro de viajes de Benjamin de Tudela, Barcelona, Riopiedras, 1989.