Walks through Almería

“When the castle of Almeria comes to sight, you will be close to an ocean of generosity, its port made of pearl and coral. As you depart from there, your heart will be filled with memories.”

Ibn Darray al-Qastalli

The Cerro de la Alcazaba (citadel’s hill) was firstly occupied in prehistoric times, in a period that could be dated in the Bronze Age. Phoenician findings were unearthed centuries later, in pre-Roman times. From the Roman period, there are numerous remains of hydraulic constructions and pottery fragments found in the excavations, comprising a wide chronology, from the first century AD to the last productions of fine ceramics, with special prominence on the final or late Roman period (5th to 7th centuries).

This occupation suggests the possibility of the continuity of this habitation until the “foundation” of the city in 955, on the basis of an existing small maritime population dependent on the interior land (Urci, the Bayyana Muslim, actual Pechina), current Pechina), of which it was its natural port and whose vestiges are to be found in several parts of the present-day city. The first reliable records of Muslim Almería date back to the 9th century, when ‘Abd al-Rahman I entrusted the surveillance of the coast to a group of Yemenis in order to prevent the Normans from landing there. Along with the Indigenous population, a marine republic was founded, based in Pechina, whose wealth was founded on trade, especially with Northern Africa.

Pechina grew in size and soon acquired the attributes of a real city, while Almería was in the 9th and the first half of the 10th century the maritime district of Bayyana. Inhabited by merchants and fishermen, was defended by a watchtower in order to control the bay easily. This watchtower was located at the highest point of the Cerro de la Alcazaba, in what is currently the third enclosure. The town was named after this watchtower: Al-Mariyat Bayyana, that is, Pechina’s watchtower. After the victorious fight against the Mozarab rebels, ‘Abd al-Rahman III (912-961) ordered to transfer the capital of the cora of Pechina, and the so-called Pechina’s watchtower was given the title of “city”. A Great Mosque was founded, and a wall was attached to the fortress. The city was erected around a walled central core, the Medina, where the Great Mosque or Aljama, the Alcaicería (silk market), the Atarazanas (shipyards) and the souk were concentrated. This was the beginning of the growing relevance of Almería as a coastal city and commercial port, reaching special significance in the trade with the Mediterranean lands.

The religious and commercial core was surrounded by the suburbs: Al-Hawd and La Musalla, that became independent towns, where the population was grouped according to their origin, beliefs and trades. In 1009-10 the Civil War broke out, and the city became one of the most flourishing ones of the Taifa kingdoms. After the dissolution of the Caliphate and after Hisham II’s death, Khayran took control of the city, made it independent from Córdoba and turned it into a Taifa kingdom. Khayran enlarged and reinforced the fortress, and Al-Mutasim achieved ephemeral glory by surrounding himself with writers and poets in his small, enlightened court.

In the 11th century, Almería had become the most international port of al-Andalus. The most exported product was silk because of its excellent quality and wide variety of fabrics, which made the city famous for the many looms existing all around.

Almería, however, was unable to resist the thrust of the Almoravids and, later on, its economic splendour attracted the attention of the Christian kingdoms, under the command of the troops of Alphonso VII. The city was taken by the Christians in 1147. Ten years later however, in 1157, it was reconquered by the Almohads. This brief conquest of the city was economically devastating.

After the Almohads, in the 13th century the Nasrid period started in Almería, and the city took part in the continuous internal struggles the Nasrid Kingdom had to face. Finally, through the campaigns of 1488 and 1489, the territory of Almería was put under Castilian sovereignty, and it was on 26th December 1489 that the Christian troops entered the city.

In the end, it was during the Muslim period that Almería reached its maximum splendour, especially during the 11th-12th centuries, after the collapse of the Caliphate of Córdoba, becoming a populous civilization centre. Seven centuries later, in the mid-19th century, it would reach again important social and economic vigour thanks to mining and the grape trade, which enriched the bourgeois classes.

Nowadays, Almería has a strong economy, the most important resources being tourism and the agricultural sector, especially the cultivation of greenhouse crops.

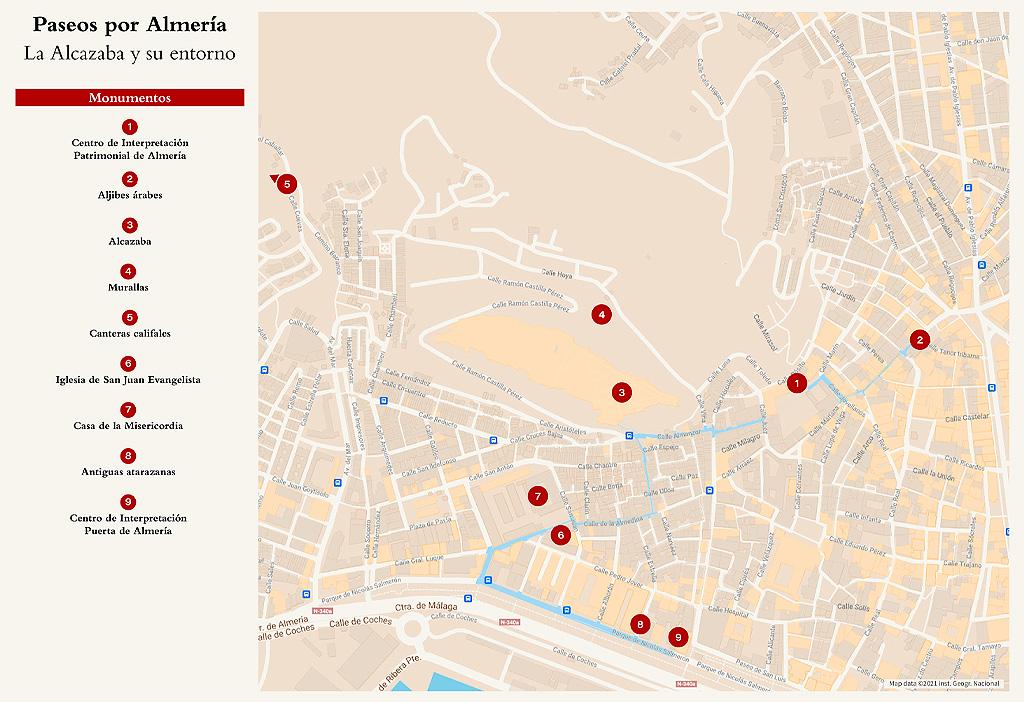

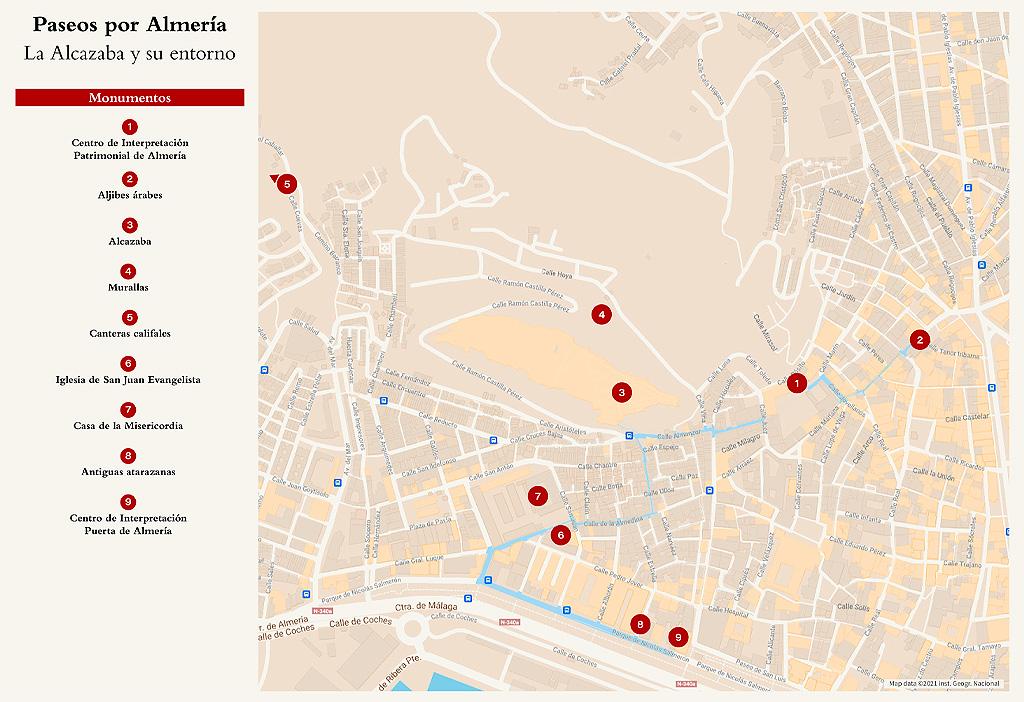

1. The Alcazaba (citadel) and surrounding area

Our first walk around Almería starts in Plaza Vieja, currently named Plaza de la Constitución. This will be the starting point for more of these Routes, so we will learn about it later on. As the first essential point of any Route to the city of Almeria, we cannot miss a visit to the Heritage Interpretation Center of Almeria, located on one of the sides of the square.

Download plan for Walk 1. The Alcazaba (citadel) and surrounding area

It is impossible to comprehend the culture of a place without having an overall vision, beyond data, analysis and style, of its sites and monuments. And it is precisely a visit to the Heritage Interpretation Center that will supply us with the keys and guidelines to understand, beyond merely analytical descriptions, the sense and way of feeling of the city, its history and evolution.

In the exhibition floors of the Center we can take a thematic tour, starting on the ground floor, focused on Muslim Almeria, going from its foundation in the 10th century until the city was conquered by the Catholic Monarchs. Special attention should be paid to the scale model of the Alcazaba (citadel). On the second floor, we can take a tour through Christian and contemporary Almería, by means of exhibition pieces and an attractive interactive device. On the third floor, devoted to modern-day Almería, we can also contemplate the magnificent views of the city, the walls and the Alcazaba, from the top of the terrace.

Once we have seized an overall idea of what Almería has to offer, we will take a detour on the opposite direction to the Alcazaba along Tiendas Street up to the Arab cisterns of Khayran.

If the overall view is essential in order to understand Almería during the period of al-Andalus, which is the leading thread of our first walk, not less important is to discover one of the great achievements of this period: the establishment of the hydraulic infrastructure that supplied water to the population and the troops. The cisterns, although popularly known as cisterns of Khayran, it is not clear enough whether they were his work or his successor Zuhair’s, both kings ruling during the 11th-century taifa kingdom. In any case, the building is part of the hydric network that supplied drinking water to public fountains and pillars. Water came from the fountains of Alhadra and the cistern, located outside the city walls, and was transported through an underground irrigation channel up to Pechina or Purchena Gate, which no longer exists.

The existing remains of the cistern consist of three brick naves covered with vaulted ceiling supported by pillars and arches. The space is currently used to house exhibitions.

Back in Plaza de la Constitución, we will get across the arch on the left side of the City Hall, and we will head towards the Alcazaba along José María Acosta and Almanzor Streets. From the latter street we will move parallel to the enclosure walls until we reach the entrance staircase to the Alcazaba.

The Alcazaba is undoubtedly the most emblematic building in the city of Almería, not only for shaping the city skyline, but also for being one of the crucial elements of its urban structure. It can be distinguished from any point in the city of Almería, being the largest of the citadels built by the Arabs in Spain.

The monumental complex is currently divided into three enclosures. The first two dating from the Muslim period, while the third one has a Christian design.

The main gate to this fortress, that opens in an albarrana or forward tower, known as Torre de la Guardia (Guard Tower), leads to Puerta de la Justicia (Gate of Justice) through a zigzag slope recently constructed, and protected by the Torre de los Espejos (Tower of Mirrors), which owes its name to the legend of the existence of a set of mirrors intended for sending signals to the ships approaching the city’s port.

In the First Enclosure, currently landscaped, the archaeological excavations conducted during the remodelling works of the gardens have unearthed two residential quarters and a cemetery. Today, the only construction still visible therein is a cistern and a waterwheel well capable of raising water from a depth of 65 meters.

At the eastern end is the Baluarte (Bastion) del Saliente, a perfect spot from where to contemplate the stretch of wall that runs along La Hoya and the hill of San Cristóbal, and which was built during the reign of Khayran in order to defend the new quarters of the city. From here we raise, next to the northern wall, to the esplanade of the Muro de la Vela, which separates the first and the second enclosures, and is crowned by a belfry with a bell, cast in 1763, which warned people in case of danger and, at the same time, indicated the irrigation shifts for the crops in the fertile plains.

The tower at the southern end of Muro de la Vela gives access to the Second Enclosure, the essential core of the Alcazaba, which shaped a small palatial city with all the necessary facilities. In this enclosure it is possible to visit a cistern from the Caliphate period and the Mudejar hermitage of San Juan, a 16th-century Christian building. In front of it, two Muslim houses were rebuilt in the 1960s. Attached to the northern wall are the so-called Baños de la Tropa (Troop Baths), an 11th-century construction that remained in use until the 17th century.

Our route continues towards the area where the palace was once located, that was separated by a thick wall from the rest of the buildings, and where a public area intended for government functions, and a restricted area -the king’s residence-, have been documented. To the north of the palace area is the body of a tower added in the 13th century, the Muro de la Odalisca (Odalisque Wall).

After crossing the entrance moat, we enter the Third Enclosure: the castle, that was accessed through a drawbridge. The interior is arranged around the parade ground, in the center of which there was a cistern and a silo that was occasionally used as a dungeon. To the right, the Keep overlooks the enclosure, and the towers of La Noria (waterwheel) and La Pólvora (gunpowder), raise afterwards, showing several old artillery pieces and excellent viewpoints over the port. The Keep shows a Gothic doorway with the Catholic Monarchs’ heraldic coat of arms on it. The interior reflects its original function as a residence. From the viewpoint over the courtyard of the third enclosure we can admire the port and the old city, as well as magnificent sunsets, so it is not difficult to imagine what the medieval city was like as seen from here.

Standing at this point, and taking a look to the opposite end, beyond the northernmost of the three towers that precede the Keep, we can also contemplate an entire panorama of the preserved remains of the Walls of Almería. Let us imagine what the walled city would have been like in its original forms, following the route of the visible wall that descends from the Alcazaba, on its northern side, along the ravine of La Hoya to Cerro de San Cristóbal and then back down Antonio Vico Street. We can draw imaginarily the perimeter of the wall, a major part of which was demolished in 1855 and which had been ordered to be built by Abd al-Rahman III, along with the rest of the buildings, upon the foundation of the city.

The eastern stretch of the wall, of which few remains have been preserved today, started in the fortress’ Espolón (embankment), went down Reina Street up to the sea, ran parallel to the coast westwards and went up again along Socorro and Impresores Streets, until it joined the western end of the citadel, next to the later Torre de la Pólvora (Gunpowder Tower). Several gates opened up along its perimeter, three on the eastern wall, the Carnicería Vieja (old abbatoirs) Gate, which provided access to the Alcazaba, the Gate of La Imagen (image) or Gate of El Águila (eagle), located just by Almedina Street and the Gate of Los Aceiteros (oil merchants), also called Gate of Las Carretas (wagons), which connected with the fertile plains. On the southern flank were the Gate of Las Atarazanas (shipyards) and the Gate of El Puerto (port), while at the southern end of the western wall was the Gate of El Socorro (relief) or La Sortida (exit), which was the exit way to the wharf from the interior of the medina.

From this same point, but looking northwest, to the left of the bridge over the motorway in the background, we can notice a cavity in the mountain: they were the Caliphal Quarries, places for stone extraction that covered the construction needs of the city from its foundation until the beginning of the 20th century. From the two main quarries came the stones that were employed to build the shipyards walls, or those used in the remodelling of the Alcazaba, the Cathedral and other later great public works.

Once we have got out of the Alcazaba, we will stop at the small square Mirador de la Alcazaba, where the sculpture of King Khayran is placed. Going down the stairs, we will reach Descanso Street, that stands out because of its beauty. Looking back, we will envisage a unique view of the street, with the Alcazaba in the background, which is well worth a photograph. Then we will turn down Almedina Street, a narrow street heir to those existing in al-Andalus, where we can continue to admire the Muslim heritage with the characteristic slopes, twists and turns of the urban planning of that period. We will pay special attention to the Church of San Juan Evangelista, our next destination, whose entrance is on one of the sides. Provided with a simple late Mannerist façade, it is not recognisable at first sight due to the absence of towers or belfries, and only the curved chamfer in its simple cushioned façade testifies it.

The current Church of San Juan was built during the last quarter of the 17th century on the site of what was once the city Great Mosque and later the first Christian cathedral, which was destroyed after the 1522 earthquake. Its construction took advantage of the still-preserved qibla wall. Its construction took advantage of the still-preserved qibla wall. The rest of the ancient building was dismantled, and the materials used for the construction of the Church of San Sebastián.

-

A view of the Alcazaba and La Chanca neighbourhood from the Lighthouse of San Telmo.

-

Mihrab of the ancient Major Mosque, current Church of San Juan.

-

Cerro de San Cristóbal and Walls of Khayran.

The mihrab, discovered in 1930, was used as a chapel, and preserves part of the original stucco decoration from the Almoravid period. The original roof of the church, destroyed during the Civil War, was replaced by a barrel vault with a coffered ceiling following contemporary criteria in line with the history of the building.

Leaving the church and walking down the street towards the sea, on the right, we come across the façade of the old Casa de la Misericordia (House of Mercy), today the headquarters of the Social Institute of the Armed Forces. It was built in 1784 on the site of the mosque’s ablutions courtyard. In addition to its “baroqueizing” façade, the porticoed courtyard known as Patio de los Naranjos (Orange Trees), perhaps an evocation of the courtyard of the mosque that no longer exists, stands out.

We walk down a few more metres until we reach Nicolás Salmerón Park, moving eastward, enjoying its leafy vegetation and envisioning the line of the coastal wall that used to occupy the place. On the left, we can stop at number 28, where we find the Casa de la Cruz Roja (Red Cross House), in what used to be Don Fernando de Roda’s house. This building, designed by the architect José Marín-Baldó Caquia and dating from the 19th century, stands out for being the last and most elegant example of Elizabethan domestic architecture in the city of Almería. In addition to its notable artistic interest, it is remarkable to know that it stands on the site where the most important Atarazanas (shipyards)from the Caliphal period stood, a time when the Port of Almería was the major one in al-Andalus due to its commercial and military relationship with Northern Africa and the rest of the Mediterranean.

The atarazanas (shipyards) were the places where ships were built and repaired, and all the works related with navigation accomplished. According to the scarce documentary sources we have, Almería shipyards were ordered to be built by ‘Abd al-Rahman I in the suburb of the mariyyat Bayyāna (the port of Pechina).

In 955, after the landing and subsequent attack by the Fatimids, who destroyed the city, ‘Abd al-Rahman III founded the city of Almería, which brought about the (re)construction of the shipyards, together with the fortification of the city center. All these events turned the port of Almería into the most dynamic one in al-Andalus, and also an anchorage and arsenal for the Caliphal troops, which at that time consisted of more than two hundred ships.

We move forward a few metres until we arrive to the Puerta de Almería Interpretation Center. This is a museum that houses, on the one hand, the only Roman archaeological remains preserved in the city -a salted fish factory-, and on the other, the remains of one of the gates of the wall, which some authors suggest could be the “Puerta de las Atarazanas” (shipyards Gate), given its proximity to the old building, so it would have communicated the shipyards with the port.

In addition to the contents, what is noteworthy of the Interpretation Center, managed by the Regional Government of Andalusia, is that it was developed after a debate held in the city about the conservation of this kind of remains, which were unearthed in what was the first urban archaeological intervention in Almería.

2. The Cathedral and surroundings.

[…] And thou are so bewitching, noble city

that, seduced by you, from your soil

spring never departs!

Francisco Villaespesa

Intimidades. Flores de Almendro (1916)

Download plan for Walk 2: The Cathedral and surroundings.

Our walk begins in Julio Alfredo Egea square, located halfway along Campomanes Street, where the Instituto de Estudios Almerienses (Institute of Almería studies) is located, and here is our first stop, the Palace of the Viscounts of the Castle of Almansa, current headquarters of the Provincial Historical Archives.

It consists of two buildings, joined at the back, of which only the façades have been preserved. On the one side, the Palace of the Viscounts, dates from 1780 and is one of the last examples of stately architecture, showing transition elements from Baroque to Neoclassicism. The balconies are an example of this transition with Baroque elements on their shelves and Neoclassical-style semi-circular pediments on their capstones. Behind it we find the second building, which has an exit to Infanta Street and was the house of Don Francisco Jover y Tovar, mayor of Almería between 1891 and 1895. The building was designed by the municipal architect Trinidad Cuartara Casinello in 1894 with a monumental façade of rustic ashlars and a formidable balcony. Inside, there is a small courtyard which is now covered, supported by four sturdy Tuscan columns. Some of the Archive collections that are worthy of our attention are on display therein.

From Infanta Street, and following along Conde de Xiquena Street leftwards, we reach the Cathedral square. This is one of Almería most characteristic urban spaces, intrinsically linked to the activity of the city and the bustle and hustle of the Cathedral itself, that is located on its southern side. Since the 16th century it was used as fish market, church’s atrium, the scene of civil and religious ceremonies and a meeting point for festivities and rogations including performances of autos sacramentales and other shows. It underwent many modifications over time, until it adopted its fairly regular quadrangular appearance. We owe its current appearance to the architect Alberto Campo Baeza, who in 1979 designed a space paved with marble form Macael, and planted high palm trees in it imitating the pillars and vaults inside the cathedral.

To the north we find the Episcopal Palace, the residence of the prelate, which is why this square was once also known as “the Bishop’s Square”. It has been located here since the 16th century, although the current building dates from the end of the 19th century and was designed by the architects Trinidad Cuartara Casinello and Enrique López Rull, to whom we owe many works that we will have the opportunity of visiting in our walks around the city. Until they occupied this building, the bishops dwelt in various houses around this place that were acquired by Bishop Fernández de Villalán, successively transformed until they made up a palatial building, greatly affected by the successive earthquakes suffered by the city, especially the one in 1804, which left the place almost uninhabitable. It shows an eclectic style, typical of the century in which it was built, while its main façade displays a simple decoration that combines medieval architectural elements with classical motifs.

On the eastern side of the square we find the priestly residence Juan de Ávila, a contemporary building erected in 2001 on the site of the former seminary. The building, of simple and functional lines, consists of two constructions separated by an interior street that retrieves the layout of the old road that used to connect the Muslim gates of the Almedina and the Eastern gate, the route from the city to the fertile plain. The simplicity and plain lines made with contemporary materials blend in with the aesthetics of the square and its surroundings.

As we stand in the square, and while we observe the masterful main façade of the Cathedral, by Juan de Orea, located on one of the sides and open to the square, we can review some historical notes.

The cathedral of Almería was erected in 1492 by the Primate Cardinal of Spain, Don Pedro González de Mendoza, being assigned its location in the main mosque of the city, later the Church of San Juan, located in the old medina and which it has already been visited in the first of our walks. It remained active until 1551, when it was transferred to its current location, partly due to the damage suffered in the earthquake of 1522 and especially due to the wish of the archbishop at that time, Diego Fernández de Villalán to ennoble the city with a new temple, in accordance with the importance of Almería in that period as defence of the coast of the Kingdom of Granada and the interests of the imperial policy of Emperor Charles I in the Mediterranean and North Africa, with Almería as a maritime frontier. It was the emperor’s order, an unpopular decision, to supply the building with a defensive character and to locate it outside the medina, in the heart of the suburb of La Musallá, a fact that would mark the subsequent urban development of the city. This explains the building layout as a cathedral-fortress, with very characteristic features such as a military structure designed to face the continuous attacks of the Barbary pirates who ravaged the Mediterranean coasts, or the tower built as a Keep. Its architecture is a transition between late Gothic and Renaissance, with later Baroque and Neoclassical elements, making it one of the most important architectural examples in Andalusia. The two doorways designed by Juan de Orea are particularly outstanding, as well as the magnificent choir stalls and the Chapel of Santo Cristo, with the impressive sepulchre of Bishop Villalán, also by Juan de Orea. It is possible to take guided tours in the interior of the temple and to the exhibition room, so that we can contemplate the Purísima Concepción, by painter Murillo. Surrounding the cathedral premises and, as we admire the solid military structure, we will make a stop in Cubo Street, outside the front wall of the Chapel of Santo Cristo, where the bas-relief known as Sol de Portocarreroa name that has proved to be erroneous, as it was sculpted before the episcopate of bishop Sol de Villalán.. It consists of an anthropomorphic face bordered with ribbons, which has become a symbol of the city of Almería.

A little further on we reach the landscaped Square of Bendicho, surrounding the plain monument dedicated to the writer Celia Viñas. Attached to the structure of the cathedral and due to the decrease of the attacks on the city at the end of the 17th century, various buildings were established, such as the former ecclesiastical prison and headquarters of the college of choir boys, now used as offices of the parish cathedral, or the most outstanding building, Casa de los Puche, today the headquarters of the Brotherhood of El Prendimiento of Almería. This is a sample of a bourgeois residence built around 1700, showing the typical layout of a two-storey house organised around a central porticoed courtyard and entrance hallway, and which after restoration has revealed a remarkable wine cellar with jars and the staircase tiles decorated with little birds. It houses an interesting museum of Easter Week items belonging to this brotherhood.

We continue around the outside of the cathedral, and, at this point, we might make a stop at the nearby Museum of the Spanish Guitar, which houses the oldest Spanish guitar in history, dating from 1684, manufactured by the luthier born in Almería Antonio Torres, who in turn, gives his name to the museum. Further on, turning into Duendes Street, and at the end of this street, we come across the Provincial Hospital, formerly known as the Royal Hospital of Santa María Magdalena,whose foundation was granted by the Catholic Monarchs in 1492 in the same foundation deed as that of the Cathedral. The works were promoted by Bishop Diego Fernández de Villalán and began around 1546. Its Renaissance origins can still be noticed in the porticoed courtyard, originally open on one side, facing the sea. Having suffered recurrent modifications after the 1835 confiscation of assets and secularisation, as well as the construction of the chapel and the hospice in the 19th century, the most outstanding features of the original building are the wooden panels (alfarjes), and above all the large, coffered ceiling covering the main floor, perhaps the longest preserved, as it is 37 metres long, and represents an exceptional case of carpentry in the province, as it was covering a non-religious building. It consists of a lima bordon (hip rafters) construction supported by crosspieces resting on carved head corbels and adorned with latticework and muqarnas. A monumental doorway stands out on the masonry façade, dating from 1778, as can be read in the inscription that crowns the ensemble together with the royal coat of arms of the Bourbon dynasty.

Retracing our steps, we go back to the cathedral and continue along the defensive wall of the building before reaching the nearby convent of Las Puras, one of the most important artistic ensembles in the city. At the end of Velázquez Street, at the curve with José Ángel Valente Street, we catch a glimpse of the concealed splendid 18th-century Baroque doorway that opens up to the church, where a characteristic curved lintel housing the niche stands out, as well as a dense plant decoration surrounding the coat of arms of the Cárdenas family, founders of the Convent. This façade is also characterised by the 17th-century Mudejar tower; the church, made up of a single nave, shows magnificent Baroque decoration, being the altar the most outstanding piece. The other entrance to the convent, which occupies a large area, opens up to Cervantes Street and the doorway dates from the 19th century, hidden among more modern neighbouring constructions. The building occupies a big area and was founded in 1515 as a cloister for the Order of the Franciscan Conceptionists. It is structured around a porticoed courtyard and rectangular cloister and is remarkable for its mural paintings and Mudejar ceilings.

Let us carry on along José Ángel Valente Street and, leaving behind the entrance to the convent, at the end of the street, we will find the last point on our route, the palace of the Marquises of Cabra, the current municipal archives. Stylistically, it consists of a typical neoclassical palatial house dating from the mid-19th century, in Elizabethan style, being one of the most monumental and stylistically pure buildings all over the city. It is the type of construction built by the aristocracy of the period on the main streets of the city in order to stand out socially. Provided with a harmonious and regular façade, its noble rooms are structured around a large courtyard supported by Tuscan columns, preserving the original structure, which has been changed for the new purpose of the building as far as the service rooms are concerned after the refurbishment in 2004.

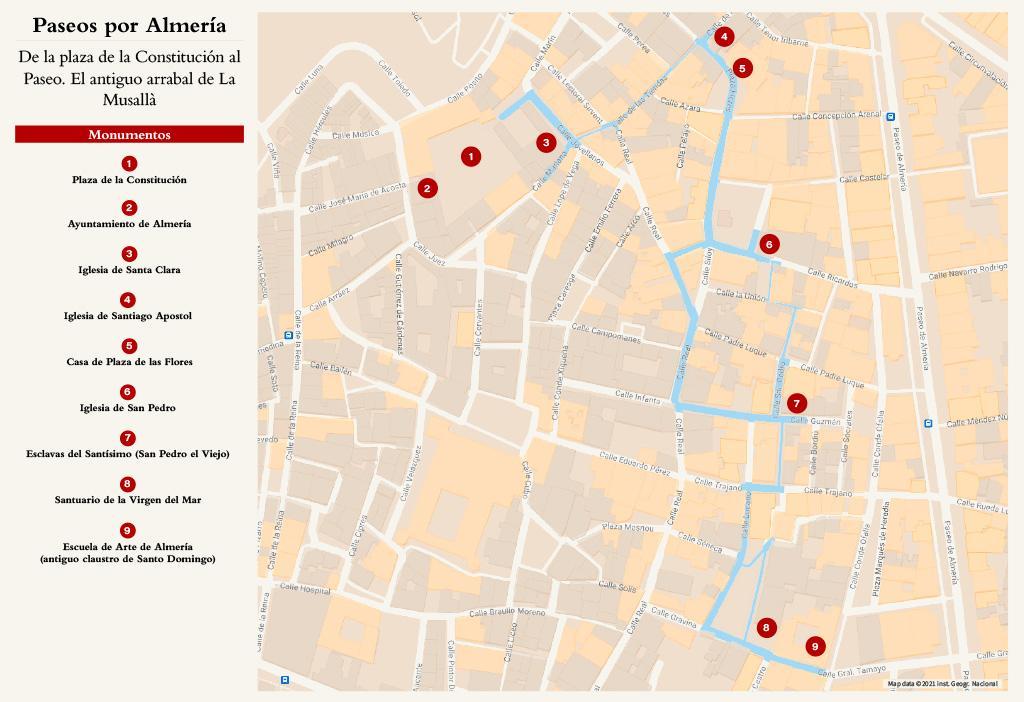

3. From Plaza de la Constitución to El Paseo. The Eastern part of the ancient suburb of La Musallà.

“How far away now, our life in Almeria!,

her cherished memories are written in gold. […]”

Ibn Yabir

Download plan for Walk 2: From Plaza de la Constitución to El Paseo.

Our Route begins in the so-called Plaza Vieja, or Plaza de la Constitución. This is one of the most outstanding spaces in the city, which in Muslim times was already home to markets and festivals and was surrounded by bazaars, inns and hammams. After the conquest of the city by the Catholic Monarchs, it was renamed as Plaza del Juego de Cañas (Game of Spears and Rods), in allusion to one of the main entertainments that used to take place here. It was not until the 17th century that the City Hall moved to this location, occupying several houses in the surrounding area.

We owe its current image to the works that were accomplished from 1785 onwards, in which the construction of arcades to accommodate the city market and the unification of the façades was planned, following the model of Plaza Mayor (Main Square) predominating in that period.

The City Hall building,, recently refurbished, covers several of the houses in the square. The façade of the main building stands out as a whole, designed by the architect Trinidad Cuartara, who in the 19th century unified the spaces and erected the main façade, the assembly hall, the staircase, the tower and the library, all in a classicist style following the urban palatial tradition.

The centre of the square is occupied by a monument popularly known as “Pingurucho de los Coloraos”, a column-shaped cenotaph in honour of the constitutionalists who rebelled against the absolutism of Ferdinand VII in 1824, and which had been originally erected in Puerta de Purchena.

Behind the square we will find the Church of the Convent of Las Claras, the only surviving building of the former Royal Monastery of La Encarnación. The foundation of this convent dates back to the times of the conquest of the city by the Catholic Monarchs, although due to various circumstances it was not until 1756 that the nuns finally took up the place. It occupied the manor houses left by Don Jerónimo Briceño de Mendoza in his will in 1590. Only the church remains from the whole convent building, and it was designed by the architect Simón López de Rojas, from Granada, at the beginning of the 18th century. It consists of two façades, the main one facing Jovellanos Street, being one of the best examples of Baroque architecture throughout the city. The interior of the church, shaped as a Latin cross floor plan, is covered by barrel vaults. Over the transept there is a beautiful dome supported by profusely decorated pendentives and an octagonal tambour on a light system formed by splayed windows that confer its characteristic illumination to the enclosure.

We will continue our walk along Tiendas Street, which we have already visited during our visit to the nearby Cisterns of Khayran. On this occasion we will stop halfway along the street, at the junction with Hernán Cortés Street. On the right hand side we will find the Church of Santiago. The first element that will catch our attention from this church is the characteristic tower-door, by Juan de Orea, built in 1522, although the church itself, Mudejar in design, had already begun to be built in previous years. The monumental doorway existing on the north façade is also Juan de Orea’s work. The church has historically undergone lots of vicissitudes, both due to the disentailments and to the Spanish Civil War, during which the most significant loss was the Mudejar ceilings. It was restored in the 1940s. Inside, the chapel of Santa Lucía stands out, covered with a ribbed vault and showing a magnificent Classicist doorway.

Next to the church, at house number 1 of the adjoining Plaza de las Flores, we will find one of the most interesting and singular buildings from the first half of the 20th century preserved in Almería. It is a noteworthy example of historicist architecture built in 1925 by the architect Guillermo Langle Rubio, in which the façade and the balcony, profusely decorated, stand out.

Continuing along Plácido Langue Street, we will reach Plaza de San Pedro, where we find the building that was once the church of the former monastery of San Francisco, founded by the Catholic Monarchs and currently the Church of San Pedro. The current building was erected at the end of the 18th century to replace the original one, destroyed by the earthquakes of 1770 and 1790, and was designed by the architect Juan Antonio Munar, from Madrid, who was also the author of the cathedral’s cloister. It is a neoclassical building with a strong academist influence and a peculiar interior area, consisting of a nave covered by a barrel vault, lacking a transept, ending in a semicircle in the presbytery, what confers the whole complex a strong longitudinal and perspectival unity.

Leaving the square along Floridablanca Street, we walk down Real Street while we enjoy what was once the main artery of the city and the heart of Almeria social life. This street, already in the Muslim period, gathered the commercial and artisan activity and was previously known as Calle del Mar (Sea), Calle de los Mesones (taverns) or Calle Real de la Cárcel (prison), as it was the site of the old prison, a building now disappeared, also designed by Juan Antonio Munar.

At the crossroads with Infanta Street, we will take a detour to visit the Church of Las Esclavas, formerly known as Church of San Pedro el Viejo. Built on the site of a former mosque, it replaced a Mudejar temple that was damaged in the earthquake of 1522. It was substituted by the current masonry construction, at the expense of Bishop Portocarrero at the beginning of the 17th century. The building has undergone many variations and changes of function, what can be noticed in the remains of the blinded openings on the side façade. It consists of a single nave, covered with a Mudejar framework, with a three-sided cloister vault which, together with the façade that no longer exists, were built by Marcio Infante, designed in the purest Mannerist style.

We continue our steps towards the square of Virgen del Mar, where we find the sanctuary of the same name dedicated to the patron saint of Almería, former church of the Convent of Santo Domingo. Adjoining it, the current School of Art occupies the space of the cloister of this prominent convent founded by the Catholic Monarchs in 1492.

The Basilica Church of Virgen del Mar corresponds basically to the building erected in the first half of the 16th century, an example of the transition from Gothic to Renaissance, like so many other buildings raised in Almería after the conquest. It consists of a Latin cross plan and three naves divided in three bays, being its most remarkable feature the roof over the transept, where the barrel vaults converge and rest on large squinches decorated with scallops. In 1936 it suffered an outrageous fire in which the magnificent baroque altarpiece, among other elements, was lost. The restoration of the building was conducted by the architect Guillermo Langle. The wooden sculpture of Virgen del Mar is the oldest religious image preserved in Almería and, according to documentary evidence, arrived floating to Torregarcía beach in 1502, perhaps as a result of a shipwreck before being transferred to the convent. It is a Gothic polychrome wood carving dating form the end of the 14th century.

The adjoining cloister of the former convent, currently the Almería School of Art, was built in the 16th and remodelled in the 18th century, consisting of two floors and a garden. In 1810 the convent was suppressed by the French, later disentailed and finally dispossessed of its paintings, library and furniture. It was used as an educational center, which caused numerous changes of layout. Some interesting remains of the cloister include the decoration of the semicircular arches with the royal coats of arms and those of the Order of Santo Domingo, a little door framed with a Gothic-style alfiz and other one in the Mannerist style. The cloister is often used for housing exhibitions.

4. El Paseo and Levante expansion area

“The fountain of Purchena Gate

is a pretext for photographers

and an ultimatum for the rainbow. […]”

Alexis Díaz-Pimienta.

Discurso del transeúnte ante la fuente de la Puerta de Purchena.

Download plan for Walk 4. El Paseo and Levante expansion area

We begin our walk in the square known as Puerta de Purchena (Purchena Gate). This is where Bab Bayyana, one of the gates opened up in the enclosure of the 11th-century walls in order to defend the Musallà suburb was located. From there, the roads to the ancient city of Pechina and the territories to the north and east departed. In the Christian period, by deformation, it started to be known as Puerta de Purchena, a name that was inherited by the square resulting after the demolition of the walls in 1855. This square is the hub of the city and has undergone successive reforms, the last of which, conducted in 2005, has left us characteristic elements such as the bronze sculpture of the Almería-born politician Nicolás Salmerón y Alonso.

There are still some relevant buildings in the square from the early 20th century, such as Casa de las Mariposas (House of Butterflies), which stands on the corner of one of its sides. The building, designed by Trinidad Cuartara and built in 1909 owes its name to the coloured metallic butterflies that decorate the handrail of the building’s parapet, a distinctive element topped by a dome. The building is decorated in an eclectic style, characteristic of the period, with modernist ornamentation on the balconies and on the staircases inside. At the opposite end, on the corner with Rambla de Alfareros street, we come across other building, very characteristic for its modernist decoration, a work by the architect Enrique López Rull in 1910, where the arches of the mezzanine floor, although designed as semi-circular, were built in the shape of a bulbous horseshoe arch. The adjoining building, although designed also by López Rull, was later redesigned by Guillermo Langle Rubio, who added glazed ceramic elements and other resources according to the regionalist taste of the time.

Some metres away is the Church of San Sebastián, in the square bearing the same name. A small mosque or rábita was built on the site, located outside the city walls, which in Christian times was replaced by a hermitage devoted to San Sebastián, under the care of the Holy Trinity friars. This was replaced by a larger temple in 1674, which was to be the seat of the parish church of San Sebastián, which served the first inhabitants of this area. For the construction, materials coming from the old cathedral of the Almedina were used. The current church is the result of the enlargement and redesign carried out in the 18th century, including a sober façade designed by Ventura Rodríguez.

Back to the Purchena gate, what is currently known as Paseo de Almeríastarts out in front of us. It arose as a result of the demolition of the city walls in 1855 and was conceived as the main urban artery of Almería, following the fashion of constructing large, aligned roads that was starting to prevail in European capitals. From its origins it was the place chosen by the bourgeois classes of Almería to build large houses and structures of greatest significance for daily and social life. As we walk along the road, we will still notice some good examples of this.

Down the street we turn left into Aguilar de Campoo street to head towards the Central Market, but not before stopping to contemplate the façade of the corner building,designed by Langle Rubio in 1924, which shows a historicist design with profuse neo-baroque ornamentation that combines with glazed ceramic decoration and other regionalist elements.

The Central Market is a work by the architect Trinidad Cuartara Casinello, that was inaugurated in 1898 and replaced the market existing in the old Square of Juego de Cañas, currently the Constitución square. It was promoted by the Town Hall and built as iron architecture, being the most original model of those built in this category in Almería up to that date. The five naves rise above an ashlar base formed by the basements, which were initially used as a warehouse and granary, and are divided by thin iron columns, which supplies the space with great transparency, and covered by an iron framework on which the red and green glazed tiles of the roof are laid directly thereon. The exterior is covered with brick walls in a classicist style, the same as the adjacent façades, designed in a homogeneous manner, forming an urban complex with low buildings. It was conceived with the provision that, if necessary, they could be covered with glass frames, which would have given rise to a commercial passageway like those built-in other 19th-century bourgeois cities.

At the back of the market, on Rambla del Obispo Orberá street, is the Apolo Theatre, a small-sized building, also by Trinidad Cuartara. It is one of the two remaining 19th-century theatres in Almería and replaced the old Calderón Theatre, although in this case only the façade remains, as it was completely remodelled between 1986 and 1992. Continuing along the Rambla we can approach the nearby Church of the College of La Compañía de María,a work by López Rull from the end of the 19th century, in which its historicist masonry façade stands out, integrated with the whole of the school, not forgetting the three naves separated by pairs of painted iron columns in the interior.

We retrace our steps along Navarro Rodrigo street, and on the right, we can admire the current headquarters of the Provincial Council, the former home of Don Juan Lirola, a liberal politician and mayor of the city at the end of the 19th century. It is the first example of an urban house-palace in Almería. Built in 1880 and extended in 1884 by Trinidad Cuartara, in the eclectic style typical of the period, it is built around an interior garden which is currently covered. Its lateral façades converge in a curved body that used to serve as the main entrance, with a large viewpoint on the upper floor. The decoration, carved in stone, is concentrated in the openings, showing curious female heads. The corbels of the balconies and the crowning cornices are also worthy of mention.

Back to El Paseo, we head down the street to Juan Casinello Square, which will mark the limit of the works on the first phase of El Paseo. We find ourselves in front of the façade of Banesto Building, erected on the site formerly occupied by the so-called Principal Theatre or Campos Theatre. It is a magnificent building, the culminating work by Trinidad Cuartara, built in 1907. In that time it was the largest building in the city, and a clear example of classicist style in the French tradition. Particularly outstanding is the circular space that projects into the square.

Further on, we come across the Cervantes Theatre and the Círculo Mercantil (Mercantile Centre), designed by the architect Enrique López Rull in Classicist and Renaissance styles, combining Baroque and naturalist elements. The interior follows the typological model of Italian theatres, with a horseshoe-shaped seating area and palatial boxes. On one of the sides is the Paseo de la Fama (Walk of Fame), which pays tribute with solid bronze stars on the pavement to the most outstanding actors and filmmakers who have worked in the province of Almería.

It might be interesting to take a detour from the promenade and visit the nearby Church of San Nicolás, formerly the Church of Sagrada Familia. It is a small chapel located in Reyes Católicos street, at the back of El Paseo, dating from the beginning of the 20th century. Its façade, in eclectic style with Romanesque and Gothic elements, is presided over by a relief depicting the flight of the Holy Family to Egypt and a small, elegant central tower. Inside, the frescoes by the painter Carlos López Redondo stand out. Not far away, we can also visit the Celia Viñas Institute, originally intended to be the headquarters of the School of Arts and Crafts. It consists of a monumental building conceived in the neo-academic style of the first quarter of the 20th century, and which is one of the architectural landmarks of Levante bourgeois expansion. Opposite one of its sides, at number 3 Eguilior Street, we find one of the few examples of domestic architecture in which modernist ornamentation dominates and which still conserves the sculptural decoration. It is the only incursion into Art Nouveau by the classicist architect Trinidad Cuartara.

-

Casino Cultural, headquarters of the Regional Government Delegation.

-

Mercantile Circle.

-

Banesto building.

Continuing our route along Paseo de Almería, we pass along the Agencia Tributaria (Tax Office) building,showing a characteristic façade of different types of stone and a balcony-gallery presided over by the coat of arms with the imperial eagle, and further on, what was the former headquarters of Sociedad Casino Cultural,now the Government Delegation of the Andalusian Regional Government, one of the most outstanding examples of Almeria’s 19th- century domestic architecture, showing red brick facings that support pilasters, pediments and stone and marble balustrades that highlight its monumentality.

The Paseo ends at Plaza Circular, presided over by the building at number 81, a work by López Rull, one of the last examples of architectural historicism with a strong influence of Art Noveau. The rest of the buildings that make up an architectural unit with the square are already part of the autarchic architecture of the mid-20th century, such as the Provincial Directorate of Social Security,the nearby headquarters of the the nearby headquarters of the on Gerona Street or the former Bank of Spain,with a classicist design and solemn façades. Next to the latter one, the Palace of Justice, which follows the same sober style as the previous ones in its composition, characterised by its distinguishing tower and the monumentality of its entrance door, with decoration of mosaics.

Right in the Plaza Circular, in contrast to what we have seen so far, we can finish our visit at the so-called Casa Vasca or Casa Montoya, that houses Doña Pakyta Art Museum. Its characteristic architecture breaks the uniformity of the surrounding buildings, and is a delightful example of regionalist architecture, although it is inspired by mountain typical architecture rather than Andalusian forms, with neo-baroque elements, designed by Guillermo Langle Rubio in 1928. Inside, the museum houses a broad overview of Almeria’s art between 1880 and 1970.

5. Almería maritime façade

The extraordinary urban expansion experienced by the city in the 19th and 20th centuries thanks to industrial developmentalism is reflected in new and remarkable buildings in the expansion areas. In this tour we will focus on the areas that were left free after the demolition of the sea wall and the opening of Almería to the port and the sea.

Download plan for Walk 5. Almería maritime façade

The Euphrates and the Tigris let no more water flow

but their two generous hands, if admitted that Almeria is Baghdad.

Thanks to him [al-Mu’tasim], the seasons and the climate are mild:

December is as sweet as September and July as April.Ibn Haddad

This route follows the line of the wall that separated the city from the port and the sea along the coast. We will start our way at the small Church of San Roque, located in what was once the Aljibe district, the current quarters of Pescadería and La Chanca. The church is built on the site of a chapel in the old Muslim quarter of al-Hawd, and was dedicated to San Roque, patron saint of fishermen and advocate against the plague. It is one of so many buildings around the city that has suffered countless vicissitudes throughout history, but the most important one was its destruction in 1936, that is why the current church is the result of a 1945 architectural project and was one of the actions of the General Directorate of devastated regions in Almería. Eclectic in style, it has neoclassical influences and is preceded by an elegant stone access staircase. From the atrium’s parapet we can seize a good view of the port and the sea.

We continue along this avenue until we reach Nicolás Salmerón Park, the city’s park par excellence. We will take a leisurely stroll along its more than one and a half kilometre-long route full of extensive and exuberant tree groves, sculptures and fountains. It is the largest green space in the city and a central part of the city’s historical identity. It replaced the space left after the demolition of the wall that separated the city from the sea. The promenade was built in two phases, the first, that spreads from our starting point to Real street, is known as the Old Park, landscaped since 1890, with large-trunked trees. The New Park, that extends its last stretch as far as the Rambla, was designed by the architect Guillermo Langle and landscaped at the end of the 1930s, supplied with assorted vegetation, which alternates trees with bushes, hedges and abundant flora. The whole complex is marked out by a series of fountains and monuments such as Fuente de los Peces (Fishes Fountain), Fuente de los Delfines (Dolphins Fountain) and Fuente del Remero (Oarsman’s Fountain).

A little before reaching the junction of the Old and New parts, we can take a detour a few metres away to visit the Andalusian Centre of Photography. Located in the building occupied in the 19th century by the Liceo Artístico y Literario de Almería, a 16th-18th century manor house, it displays the photographic collections that emerged from the Imagina project in 1992, when internationally renowned artists travelled to Almería to exhibit their works. It houses high-standing temporary exhibitions.

On our way back to the Park we continue along the path; leaving the beginning of the Rambla of Almería to the left, we head towards our next stop, the mineral loading bay, better known as “Cable Inglés” (English cable), located at the Almadrabillas beach.

It is a splendid example of industrial architecture and engineering that identifies and adds personality to the maritime façade of Almería. It is a pier-wharf built by the beginning of the 20th century and which was used to load the iron ore extracted from the mines in the town of Alquife, in Granada, which was transported by train to the same wharf and by means of a gravity unloading system was poured into hoppers located in the lower passage, which were at the height of the ships that docked on the sides of the structure and received the ore by means of platforms that unfolded and let the load fall on the ships.

Following the promenade that runs parallel to the railway line that ends at the pier, and leaving to the right the impressive monument dedicated to the people of Almería who were murdered in the Mauthausen concentration camp, we arrive at the railway station,a superb building designed by the French engineer Laurent Farge, begun in 1893, which formed part of the construction of the Linares-Almería railway line. The eclectic style achieved by a construction of iron, glass and brick never ceases to amaze the visitor with its beauty; it combines the industrial nature of the materials with the monumentality of the final result with an abundance of decorative elements of glazed ceramic that alternate with red brick, metal and glass distributed in three pavilions.

We can finish our tour paying a visit to the nearby Museum of Art of Almería,an extension of the one we have already visited in the house of Doña Pakyta, located opposite the Railway Station, in a complex that combines two buildings next to each other, the characteristic regionalist style house, designed by Guillermo Langle and built in 1927 and the post-modern building designed by the architect Antonio Góngora, inaugurated in 1988, which surrounds the former one with a plastic structure designed with a diaphanous interior of various levels. This building exhibits works from the avant-garde movements that have emerged in Almería since the 1980s, as well as photographic works and temporary exhibitions.

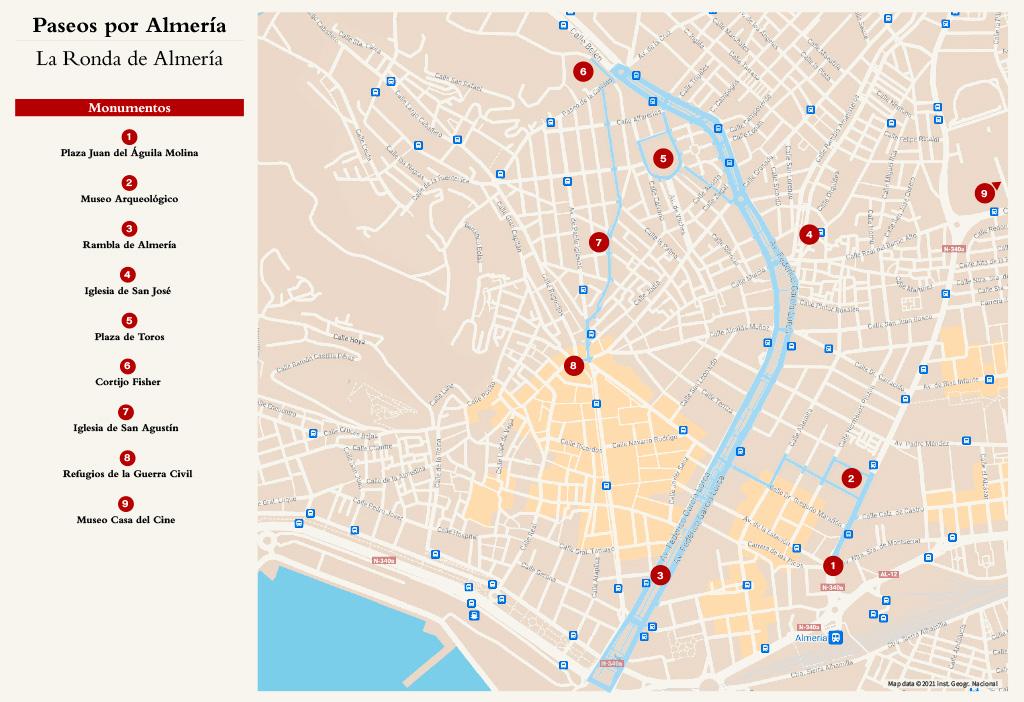

6. The Ronda of Almería

The route takes us through the most outstanding urban expansion area of the city, the result of the urbanization of the old watercourses that crossed the city, this being the most transforming event of the Almeria landscape in the 20th century.

“ […] Thou hast the Light for thy lover, O fortunate earth! Who conceives the fruit of her divine desire. […]”

Aldous Huxley. Sonnet “Almería”.

Download plan for Walk 6. The Ronda of Almería

We begin our walk in the Square Juan del Águila Molina, once known as Plaza de Barcelona. In this space we can observe numerous examples of modern architecture, such as the old Bus Station, by the architect Guillermo Langle, a notable example of rationalist architecture with a concave façade and decorative sobriety typical of his style, limited to ornamental architectural elements in its chamfers. Opposite, the remarkable steel, glass and stone building, the headquarters of the Almeria-based bank Cajamar, of recent construction, with a curved façade and juxtaposed with the opposite building of the bus station. In the centre of the square, the abstract steel sculpture by Fausto Rodríguez stands out.

We continue along the Ronda road and a few metres further on we come across the Archaeological Museum of Almería, located in a beautiful modern building designed by the architects Ignacio Pedrosa and Ángela García Paredes. It is worth sitting down for a moment in the square and contemplating this attractive building, under its garden of palm trees reminiscent of the Phoenicians and its architecture of rectangular tree pits, perhaps inspired by Egyptian temples, that lead us to the staircase to the museum entrance.

The visit to the museum combines in a didactic and visual way the presentation of pieces, graphics, illustrations, audio-visual devices and scale models, making a trip through the societies that inhabited the southeast of the Iberian peninsula since the 3rd millennium BC. Divided into three floors, the ground floor shows one of the most interesting museography resources, a full-scale reproduction of a stratigraphic section in which the archaeological strata from the bedrock to the present day can be observed. The first floor focuses on the first agricultural and livestock societies and the exhibition area dedicated to the culture of Los Millares settlement. On the second floor there is an exhibition on the Argaric culture and finally on the top floor there is a space dedicated to Roman society and Islamic Almería.

Once we have finished our visit to the museum, we head towards Avenida Federico García Avenue,where we come across one of the most important urban development projects carried out in Almería in the 20th century, the development of the old ramblas (watercourses) of Belén, Obispo and Amatisteros which, from south to north, cross the city. Designed in the form of a hall, populated with vegetation and ornamented with fountains, obelisks and sculptures, a leisurely stroll takes us to what was once the old entrance, where a wind rose and the letters forming the word Almería welcome the visitor in the vicinity of the fountain in Las Velas square. From this point we start the walk along the Rambla, as we enjoy monuments such as La Caridad, the oldest public monument preserved in Almeria, dating from 1897. We continue our walk along the Rambla until we reach the Amphitheatre, where Rambla de Amatisteros street comes together, to approach the Church of San José, an example of a recently built church designed by Javier Peña following the aesthetic proposal arose from the Second Vatican Council. It is worth seeing the group of sculptural images by the Granadan sculptor Sánchez Mesa, housed inside.

Back to the Rambla, we continue following its layout until the roundabout where Granada street converge with it and continue along Humilladero street to reach the Plaza de Toros (Bullring). Built between 1887 and 1888, it was designed by the municipal architects Trinidad Cuartara and Enrique López Rull, in a monumental eclecticism with classical roots, characteristic of Cuartara’s works. It shows three monumental façades, the main one in the form of a triumphal arch with the upper body showing the characteristic horseshoe arches. Inside, iron dominates the structure of the upper floors, railings and the slender columns that delimit the balcony and the grandstands.

Our route along the Rambla, along Belén Street, ends at Cortijo (farmhouse) Fisher or Villa Cecilia, the current headquarters of the Andalusia Women Institute. Recently restored, it was built at the end of the 19th century and was a suburban villa and the Herman Fisher’s family, who was consul of Denmark in Almeria and a prosperous merchant in the export business of table grapes. It consists of a magnificent three-storey building in the Modernist style, with Art Nouveau decorative details.

We look for Cuzco street and will head towards our next point of interest, the Church of San Agustín. On the route along this street and the continuation along Doctor Paco Pérez street we can see some examples of typical Almerian architecture, the so-called “casas de puerta-ventana” (window-door houses). This is a typology of housing that was typical of the working class of Almeria in the second half of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, characterised by being narrow, elongated, box-shaped houses, with a hallway and corridor that crosses the house to the back, where the kitchen and the patio or courtyard open up. On the façade, which is taller than it is wide, there are two openings, a door and a window. Specially interesting is the decoration with stone masonry mouldings.

The Church of San Agustín is located in Rambla Alfareros street, at the end of Doctor Paco Pérez street. Built in 1931 and later restored by Guillermo Langle Rubio in 1947, it has a Neo-Baroque style with a basilica-shaped interior, in which the main chapel stands out, with paintings by the Dominican friar Joaquín Delgado in 1954. The processional images are also noteworthy, like the Descent from the Cross by Eduardo Espinosa Cuadros, and the Virgen del Consuelo, by the Sevillian artist Antonio Castillo Lastrucci.

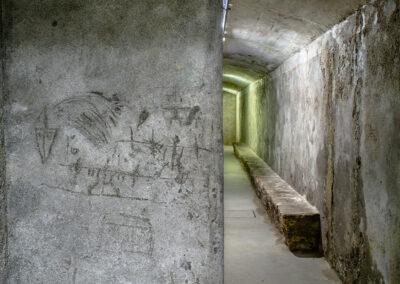

After this brief visit we will proceed to Purchena gate, following Rambla de Alfareros street and Pablo Iglesias Avenue, where we will visit the Spanish Civil War Shelters. These air-raid shelters were built after the intense bombardment suffered by Almería in May 1937 and were designed by the municipal architect Guillermo Langle. They constitute a network of tunnels more than 5 kilometres long and 9 metres deep, with a capacity to house 34,000 people, and are currently one of the largest shelters in Europe. Part of the route therein was restored in 2006, with recreations of spaces such as an operating theatre, a warehouse or a private shelter. As a curiosity, some of the original entrances to the shelters can still be seen, reconverted into kiosks, in Purchena Gate.

Although far from this route, we must recommend a visit to a space located in the neighbourhood of Villablanca, known as Cortijo Romero, in the street of the same name, which houses the Casa Museo del Cine (Cinema House Museum). This building claims special interest as it was home to the musician John Lennon, whose stay here inspired his famous song Strawberry Fields Forever. In the venues, it is possible to take a journey through the relevant cinematographic past of the province of Almería, preserving its historical memory.