Baena, in the Highland domains

According to Al-Idrisi, the noted 12th-century geographer from Ceuta, the city of Bayyana (Baena) was “a large fortress built on an elevated land which rises above the olive groves, wheat fields and fig trees that surround it”.

As we approach to Baena, the lanscape turns increasingly dense, ushered by high hills that step by step are covered fully by olive groves. These are the dominions of the Campiña Alta, the Highlands. In the background, the buttresses of the Subbetica mountains can be seen clearly, announcing the imposing range that expands southwards. The layout of this thousand years old route ties in with the passage that the Guadajoz River opens before reaching Baena, which lies in the crossroads that comes to a fork: one leading to Cabra and the southern countryside, and those streching toward the east, in the direction of Alcalá la Real and Granada.

These lands, which have been inhabited since prehistoric times, experienced at the beginning of the 1st millennium b.C a notable demographic growth, as shown by the many fortified villages that arose in the Highlands. It seems probable that in those times, the centre of gravity of the settlement in interior Andalusia was along the sides of the Baetica depression rather than in the floor of the Gualdalquivir valley, where centuries later the urban sprawl would prosper. This flourishing, as the result of the evolution of the native Turdetan element and the Punic influence, was the substrate of Iberian culture, which from the 3rd century b.C. was assimilated into the Roman world.

Among the abundant evidence from the period, there are many zoomorphic sculptures, like the lioness of the hill of Minguillar, a she-wolf nursing her young, bulls… etc., associated with necropolis and funeral monuments, and citadels with gigantic walls, like the ones of the Cerro (hill) de los Molinillos, Torre Morana or Torreparedones.

View of one of the sections of Torreparedones Archaeological Site

All these spots, along with a trail of watchtowers, marked out the so-called “Iberian Way”, the connecting point between the High and Low Guadalquivir River. The strategic road crossed the Guadajoz River and went along the Marbella riverbed, passing by the plot where Iponuba stood, now dissapeared. It has been suggested that its appelation might also come from Baius, the name of one of the owners of the rustic villas that were established in their surroundings.

We should wait until the end of the 9th century, after the arrival of the Muslims, to pass on the first direct reference to Baena, named Bayyana in Arabic and mentioned on account of the rebellion of Umar Ibn Hafsun. Around the year 890, the Muladi warlord took the city of Baena as he was advancing toward Córdoba, a moment when the city might have been relocated to where it is today. In the 10th century, during the splendour of the Umayyad caliphate, Bayyana stood out in special relief, as it belonged to the cora (province) of Cabra. Afterward it became the political centre of the province, given its strategic position in the approaches to the Guadajoz valley, and it appears as the head of its own constituency towards the years 934-935. Endorsing the prosperity of these decades are references made by Muslim doctors who were originally from Baena, like the illustrious Qasim ben Asbag al-Bayyani (861-952), a grammarian, theologian, historian and geographer who travelled and studied in Baghdad and lived in Córdoba. Baena’s fortune would fade after the downfall of the califate, and it would be recovered later under the rule of the African dynasties of the Almoravids and the Almohads. Repeteadly Baena is mentioned as one of the main cities of Al-Andalus, praised for its agricultural productivity and its urban development, which was under the protection of a “well defended, largeqasbah (castle).” A mediados del siglo XII, al-Idrisi resaltaba que Bayyana era “una gran fortaleza construida sobre una eminencia del terreno rodeada de olivares, campos de trigo e higueras”

Above, two pictures of the Arab Castle of Baena before and after restoration work.

With repeated insistence, Baena appears involved in the struggles that provoked Christians and Granadan raids and campaigns in either direction, participating ̶ fortress and people ̶ in a decisive way in many combats and truces. In this way, in the year 1300 Muhammad II targeted a harsh attack against the population that, however, resisted the assault. While this event was taking place, a singular duel between knights from both sides gave rise to the coat of arms of the village, which bears the heads of the five Muslims, in commemoration of the victory of the Christians champions over their Nasrid rivals. Once the regent -princes don Pedro y don Juan- were defetead and dead in Sierra de Elvira in 1319 before Ismail I, the cities on the Cordoban border were forced to sign hasty cease-fires, signed in Baena. Later, in the winter of 1408, the troops that had left the city succeeded in destroying in the nearby fields the army of the bellicose Muhammad VII, who had besieged Alcaudete, and later on ̶ in 1433 ̶ , took part in the famous encounter in which Boabdil was captured, who, according to some versions, was imprisoned in the castle of Baena. At the same time, Baena excelled as a thriving cultural center, cradle of Juan Alfonso de Baena (1375-1435?), who compiled the famous Cancionero ̶ which included 576 compositions from 56 poets ̶ , essential for knowing Hispanic literature. As a postcript of this medieval age, it is worth mentioning the stay in Baena of queen Elisabella the Catholic while the preparations of the final battles against Granada were taking place. In those times Baena belonged first to people of royal blood, later to be dependent of the council of Córdoba, and by the end of the 14th century, to diverse lords until becoming the property of Diego Fernández de Córdoba. His lineage, cut off from the House of Aguilar, formed its own bloodline, one of the most illustrious of the Cordoban nobility. Under their patronage, countless monuments were built in the city, and it expanded in economy and demography. In 1566, these lords, holders of the title of Counts of Cabra from the 15th century and that of the duchy of Sessa since the beginning of the 16th century, received the title of Dukes of Baena.

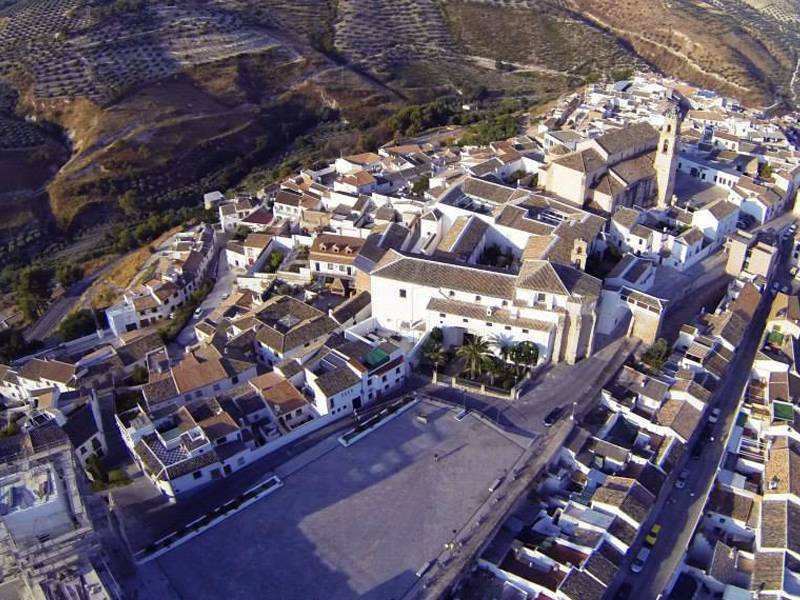

Baena’s urban ensemble unfolds on a hill topped by the quintaessential Almedina, the heir of the medieval walled city. From its slope until the plain, its streets and promenades develop in a layout traced throughout the following years.

The Almedina was enclosed by a wide belt of walls with a castle in the higher part. LThe first defensive works go back to the 9th century, which perhaps were set on a Roman bastion. These walls were reinforced during the caliphate, and later on by the interventions of the Almoravids, the Almohads and the Christians until they reached their definitive configuration. The castle, which at one counted two gates and seven towers, was remodelled at the end of the Middle Ages by Fernández de Córdoba to arrange it as their residence. Its eventual abandonment turned it into a quarry for other buildings, reducing it to the remains that today stand opposite Palacio square, a privileged lookout that dominates a wide view of the countryside.

In the core of the Almedina, the church of Santa María la Mayor stands out, probably built on the plot of the aljama mosque. With a beautiful façade in a Gothic style and a slim tower, it was mostly built in the first third of the 16th century by architect Hernán Ruiz I, and it was refurbished in the 17th and 18th centuries. Divided in three naves and covered with ribbed vaults, the church hosts a beautiful grille from the 16th century, altarpieces and other artifacts worthy of attention.

Night view of the Church of Santa María la Mayor that, according to some theories, it was built on the former site where Baena aljama mosque was standing.

Nearby, facing the castle, is the convent of Madre de Dios, one of the earlier Rennaissance examples in the province of Córdoba. Founded in 1510 by the fifth lord of Baena, Hernán Ruiz I started to build it toward 1525, succeeded in the work by his son Hernán Ruiz el Joven (the Younger). The church shows an elaborate façade that leads to the interior of a single nave, with a barrel vault and vault. Designed by Diego de Siloé, and constructed by Hernán Ruiz el Joven, its magnificent main chapel, vaulted with a half-dome is decorated with flowered pattern reliefs, angels and apostles. The sumptuous wrought iron grille and the pieces of tiling from the 16th century, the main altarpiece in marble, the choir stall in walnut wood from the 17th century as well as a large pictorial repertoire, are all part of a rich artistic patrimony. Among the popular houses and the noble manors along the Almedina, and the steep slopes around them, stand some other notable buildings like the old hospital Jesús el Nazareno.

Outside the walls, the parish church of San Bartolomé was built in the 18th century in Gothic style, related to the placement of an older mosque. Nearby stands the convent church of San Francisco, founded in the 16th century and built in the 17th. With a cross plan and a transept roofed by an elliptical vault, in its interior the prolix decoration of its frescoes and the main altarpiece attributed to Jerónimo Sánchez de Rueda attract our attention. A similiar chronology ̶ finished in 1774 ̶ the church of the convent of the Espiritu Santo has a nave that presides over a valuable altarpiece dated in the 17th century.

The old square of El Coso, today of the Constitution, concentrates on its sides and surroundings a considerable amount of monumental architecture. One of its main façades shows the Casa del Monte, an example of brick architecture from the 18th century, whose façade stands on colonnades, showing balconies and an altarpiece with fine plaster work.

Close by is the old Tercia, a grain and fruit warehouse built in 1795 and now arranged as Cultural Center and headquarters of interesting museums. One of the rooms of the Tercia House hosts the City Hall Historic Museum, which provides a complete journey through the evolution of the city and its territory. It includes paleontological remains and prehistoric discoveries to a multitude of artifacts from diverse cultures that left their imprints in the city and its area. Among them there are fine ceramics, sculptures, and different remains ranging from the Metal Ages to Roman, Visigothic and Muslim periods. Among other exceptional items, one finds the magnificent collection of Roman statuary, as well as the more than 300 votive offerings found in the Iberian sanctuary at Torreparedones.

Main façade of the castle with a replica of the Lioness of Baena (4th century BC) in the forefront. It is an Iberian sculpture in stone that was found in the archaeological site of Minguillar hill and currently on display in the National Archaeological Museum (Madrid).

The descent toward the Almedina and the Constitución square takes us, amid other monuments to the Jew of Baena, to José Amador de los Ríos and others remarkable figures, to the historic district surrounding it. Here, new, straighter tracks such as Cañada street, where the Museum of the Olive Grove and Oil, as well as the España square and el Llano intersection are.

In its vicinity we find the church of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, linked in its origins to a Dominican monastery stablished in 1527. Strongly transformed throughout time, its interior hosts a splendid latticework ceiling from the 17th century that encloses the presbytery, and the sculptured statue of the Cristo de la Sangre. Beyond the church, one has the gardens and groves of Ramón Santaella park, a green oasis surrounded by modernist manors and vintage olive oil mills.

In the area of Baena, spots of historical and scenic interest are abundant. From the old strongholds, watchtowers and settlements ̶ Tower of el Puerto, Morana Tower, Torreparedones, Tower and Cortijo (farmhouse) of Ízcar… ̶ to the luxuriant site of the Puente de Piedra, a work of the 18th century built on the Roman foundations crossing the Guadajoz river course, where a traditional noria (water wheel) has been reconstructed to irrigate the gardens.

Baena is a synonymous with olive groves and the most exquisite quality of olive oil. Gazing at the surrounding countryside shows something obvious: an infinite geometry of a legion of olive trees covering the slopes until they get lost in the distance, embracing the lands of its area and the nearby municipalities, from its agricultural fields to the orchards in the valleys and the rocks of the Subbética mountains; a vision that is accompanied by the intense scent of the oil mills working at full capacity during the oil season, which goes from autumn to the end of winter.

Baena, completely surrounded by a sea of olive trees, is one of the most prolific areas in the production of an internationally renowned oil for its excellent quality, thanks to the particularity of its olive varieties. The image shows a wide view of the olive grove seen from Torreparedones Archaeological Site.

The modern Museum of the Olive Grove and Olive Oil of Baena is housed in a restored old oil mill, and it offers the opportunity to know in detail the many aspects of the olive oil culture, from its historical background, its uses and gastronomy to the cultivation methods of the olive tree and the procedure to elaborate olive oil ̶ the milling of the olive, its pressing, the decanting of the juice… ̶ .

This interesting tour can be complementated by visiting some local olive oil mills, like the mill of Santa Lucía, which preserves all the vintage machinery of a traditional oil factory, and a winery from 1795 with the classic half-buried earthenware jars, that were used yesteryear to store the olive oil.

By Fernando Olmedo, historian

Baena has kept over more than four centuries the singularity of its Holy Week celebrations by adding drama and artistic wealth to this religious event. The Coliblancos and Colinegros Jews are the most representative characters that take part in the Semana Santa in Baena. The Coliblancos and Colinegros Jews are the most representative characters that take part in the Semana Santa in Baena. This tradition of the 19th century consists of two rival parties formed by the so called “turbas” (crowds) that accompany their corresponding confreries (one of white tails and other black) in the processions and other rituals to the sound of drums, and their names refer the colour of the horse tails that adorn their helmets.

Tamboradas of Baena, drum-playing rituals, were declared Intangible Cultural Heritage by UNESCO in 2018.